Lots of nice wine tastings coming up in Bangalore. One with Food Lover’s Magazine.

How best can you describe a wine?

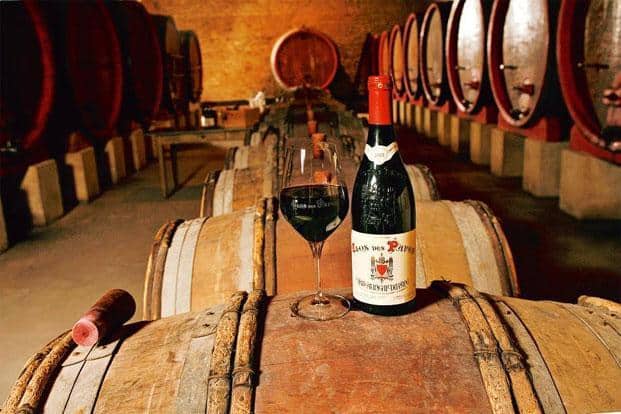

KRSMA Estates has invited me to a tasting of their wines next week, and frankly, I am a little nonplussed. Not because I dislike their wines, which I don’t, but because there is this whole brouhaha in wine circles over the esoteric terms and pretentiousness of wine descriptions. You know the kind I mean? Descriptions that attempt to illuminate the wine-drinking experience by stating that one of your favourite Rhône reds tastes like a mixture of tar, wet leather and the inside of a man’s shoes (notice the specificity—not the insides of a woman’s shoes, but the more robust, stinkier version that comes from the male chromosome). And this is supposed to entice you?

Robert M. Parker, the influential American wine critic, is often considered the originator of these long, often meaningless descriptions. He once described a Haut-Brion as having “a sweet nose of creosote, asphalt…” and an array of berries. Having never tasted asphalt, and having no idea what a creosote is, this description is absolutely useless to me.

Actually, the credit—or discredit—for wine descriptions does not go to Parker. It goes to Ann C. Noble, a professor emeritus at the University of California, Davis, whose famed department of viticulture and enology offers short wine appreciation courses that are on my bucket list.

It was Noble who came up with an “aroma wheel” to describe the flavours of wine. Ironically, she invented it to streamline things in the wine world; to bring some order into the way wines were described; to give a methodology that would simplify, not complicate things. Look at how that turned out.

Today, there is a reverse trend: wine professionals trying to puncture the opaqueness of wine descriptions. The American Association of Wine Economists has “waged a nearly decade-long crusade against overwrought and unreliable flavor descriptions”, as illustrated in a recent article in The New Yorker by Bianca Bosker titled, “Is There A Better Way To Talk About Wine?” The article quoted several sources, including the Journal Of Wine Economics, which stated that the wine industry was “intrinsically bullshit-prone”. No surprise there as anyone who is caught standing next to a swish-and-sip bore at a party can relate to this.

Some wine descriptions make sense. You drink enough Australian Shiraz and you will learn to identify the thick, viscous, fruity taste that is often described as “jammy” by aficionados. The same grape varietal, when grown in France, does not have this taste, but I have never had the pleasure of drinking an Hermitage Syrah to be absolutely certain of this.

For me, “minerally” wines are easy to identify. They taste pretty much like the water I drink first thing in the morning. A year ago, a well-meaning aunt gifted me a copper lota and told me to drink from it. It would change my life, she said. For the record, it hasn’t. But I continue to drink from copper and brass containers anyway.

My aunt’s recipe for drinking water could give a minerally wine a run for its money. She stores the water in a mud pot, pours it into her copper lota to steep overnight, downs it first thing in the morning in one shot and then proceeds to vomit. I have tried the first part of this experiment, and, I have to admit, the water tastes of copper, mud and some unidentified metal flavour that could be categorized as “minerally”. It tastes, in other words, like the Chablis wines I love.

Some descriptions just don’t make sense to me. What does “flinty” taste like? Do you have to lick a rock to figure out flinty? Some try to be overly helpful by listing a wide range of berries that the wine is supposed to taste like. Having never tasted a linden berry or even a raspberry in its natural, just-picked state, my palate has no clue how to process this information.

Which is why I was glad to see wine guru Jancis Robinson describe the 2005 vintage of Burgundy reds as “surly and tough” early in their lives. Surly, I can relate to. Surly is how we pucker up when we taste some tight reds that have been stored for far too long in state warehouses—although people call that tannic as well.

When I choose a wine, particularly if I want to impress someone, I don’t go by the description. I usually pick one with a long French name—the more syllables the better. Château de la Tour, Château Tertre Roteboeuf, Clos de Vougeot Grand Cru Vieilles Vignes, Château Pichon Longueville Comtesse de Lalande, Domaine Georges Roumier—winners all, and ones that I aspire to drink after I win the lottery. Château Palmer is highly rated, but it is too easy to pronounce; it could use a few more syllables that cause your tongue to coil itself into asanas. It sounds like an American winery aspiring to be French.

The same applies to Indian vineyards that pretend to be European. York and Reveilo make decent wines, but isn’t it about time they lost the European wannabe nature of their names? The same goes for Fratelli and its highly regarded wines. Why not choose something like Akluj, the town in Maharashtra where the winery is based, which even non-Indians can pronounce easily and which references their terroir in that most French of ways? The Indian wine consumer is evolved enough not to need such pretensions. Particularly when we can come up with authentically Indian names such as Mandala, Grover’s, Deva, or my current favourite, Sula’s Rasa Shiraz—now, that’s a name. Contrast that with Chateau d’Ori, sans provenance or soul. Give me Dindori anyday.

This is the first of a two-part series on wine tasting. Shoba Narayan loves the name Amrut even though she isn’t a single malt buff. She tweets at @shobanarayan and posts on Instagram as shobanarayan. Write to her at [email protected]

I fully agree with you. Wine tasters’ vocabulary is a lot of -“Bull Shit”- and I am surprised that term has not yet crept into wine connoisseur’s vocabulary. My vocabulary is restricted to:

-Dry, Sweet

-Heavy body, Light body

-fruity, flowery,

and some such terms.I have never been able to make out how to describe the nose- tongue and finishing!

Yes, I do like and enjoy my wines. Can always tell if I like a particular wine or not!

Of course, you have the palate with your single malt, specialist teas and wine Kishore. :)

Hmm, I agree totally with Kishore, it looks like a whole group of aficionados have come up with entire vocabularies to puff themselves up. From my earlier comments here I guess wine is also very plural.

I guess the wine connoisseurs’ claim to fame is their ability to detect the individual flavors however subtle. The rest of us recently-unfrozen-cromagnons can barely distinguish lemon juice from sugarcane juice from tar. Sadly though the connoisseur instead of making it simpler (and thus a better experience) for the rest of us they make like the apes next to the blackmonolith oohing and aahing over the oh so slight hint of rusted copper.

Puh-lease.

Shoba — I am sorry I hit the last post too quickly and your blog name (Shoba Narayan) showed up instead of my own name. Please delete the duplicate. Sorry.

Done RG. Unfrozen “cromagans.” Nice :)