Great archival photos of two music greats accompanying this piece.

Carnatic music versus Harry Potter

How do you teach Carnatic music to a child whose idea of ‘bhakti’ is watching Harry Potter reruns ad nauseam?

Shoba Narayan

When Bhimsen Joshi or M.S. Subbulakshmi (centre) sang, the ‘bhakti rasa’ was evident. Photo: Hindustan Times

There is one phrase that leaves me wonderstruck these days. It is, “I learnt juggling from my father/mother.” Or “I am teaching my son how to play the piano.” Or “I am teaching my daughter how to play tennis.”

Insert your choice of interest or skill.

How do you teach your child something that you are passionate about without—forgive me— pissing them off? Lots of parents have figured this out, but I am abysmal at it. Carnatic music, which is what my daughter (reluctantly) and I are currently engaged in, is replete with musicians who began learning from their parents and then went on to concert-level careers. How did it happen?

Are you, dear reader, teaching your child something that you care about? Are you good at it? What do you do? Is it patience? How do you stop yourself from criticizing your children to the point where they walk away? How will they get better at it if you don’t criticize? Does it have to do with sensitivity, both yours and the child’s? Can you learn to be dispassionate about something you are passionate about? Because you need this detachment in order to be a good teacher. These are some of the questions I am grappling with.

Twice a week, I force my daughter to sit on our jhoola (swing) and learn Carnatic music from me. Much of what we sing today was codified in the 15th century by Purandara Dasa, a composer who created the pedagogy of Carnatic music. He deemed that the basic voice-training exercises would be in one particular raga called Mayamalavagowla. Dasa created the gradually more complicated exercises that allow the voice to rapidly rise from one octave to another, and create a string of notes, somewhat like a jazz trumpet. This is voice culture and it is what Carnatic music students do for hours every day—for years. At the end of it, your voice should be your slave, my teacher would say. It should move up and down three octaves with the ease and grace of a slithering snake, only faster. I tell my daughter all this during our lesson. She turns to look at the clock and says, “You said only half an hour today.” I search for an analogy that she can relate to: something modern, something more like the music she listens to.

Carnatic music is like jazz in a lot of ways, I say, even though she listens to little jazz. Emotion counts when you sing or play. A good musician can elevate a composition and bring tears to the eyes of the audience. When the iconic M.S. Subbulakshmi sang, “Kurai ondrum illai”, the entire auditorium wept. So said my grandmother anyway. The Tamil word kurai means grievance but alludes to worry in this context, as in, “I have no worries/grievances, Krishna, O lord of wisdom.”

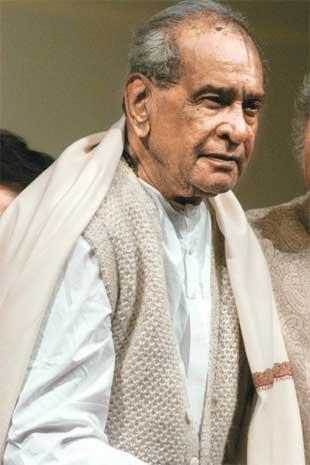

photo

Bhimsen Joshi. Photo: Girish Srivastava/Hindustan Times

I sing the tune, “kurai ondrum illai,” and my daughter sings along, having heard this song many times. It sounds odd, these words, coming from a 12-year-old. Most of our music is steeped in bhakti, or piety; or romance. One of the songs I love, “Jai Durge Durgati Parihaarini,” which Bhimsen Joshi has rendered in a stirring, spine-tingling manner, cannot be sung well without that bhakti rasa. How do you teach it to a child whose idea of bhakti is watching Harry Potter reruns ad nauseam?

Another song I am learning is from Jayadeva’s Gita Govinda. It begins on a rather cheery note: Pralaya payodi jale (The world is ending). To imbue this feeling into the song when you know for a fact that the world isn’t ending is a challenge faced by singers of

our music.

Like jazz, Carnatic music allows for a lot of improvisation. Most concerts begin with improvisation. We call it alapana. And like jazz riffs, you can traverse the musical universe with your imaginative singing and then return to the base, in time with the beat, of course. It is this bit that I cannot do. I can learn and render countless straightforward compositions, but I don’t have the imagination and confidence for improvisation. My foundation isn’t strong enough. I am worried that I will falter. I will sing one note off-key. That, I couldn’t stand. I would hate myself for getting it wrong. So I don’t even try.

My daughter tries though. She is able to sing imaginatively even if it is off-key. I crunch my hands, quite literally, and hold myself back from yelling at her. My face changes even though I channel an inner botoxed look into it. My daughter watches me turn from an easy-going mom to a tyrant. She is spooked by it. My obsessiveness comes through when I teach, which is why my children hate to learn from me.

I am as hard on myself as I am with you, I tell her when she is in tears, trying to make her understand; and forgive; and return to me to learn. My daughter approves of this self-flagellation. She watches my face get stricken when I get a note wrong. She smiles.

With music I get time out not only from the world but also from myself. So I turn on GarageBand, switch on my Snowflake mike, connect it to my SoundCloud account, download the tanpura from YouTube, feed it into my iPod which is streamed through my Bose docking station.

Surrounded and supported by these pillars of technology, I take a deep breath and search for the eternal: mokshamu galada (God grant me salvation). My daughter rolls her eyes and wishes for something similar—time out from her mother’s music.

Shoba Narayan is teaching her daughter geethams , and is trying to learn Jai Durge from Bhimsen Joshi’s CDs. Write to her at [email protected].

Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother :)

Shoba I first started to write something about “so you daughter doesn’t really like Carnatic music, either” … but then as I typed up a couple lines … it hit me, and I held down the backspace key until it was all gone. I then typed below.

For perhaps the first time I feel very sorry for you. I also feel badly that perhaps some of us have repeatedly dragged you over coals for various things. I feel bad about your sense of loss – you moved to India hoping your kids would have loved India as you do, but for the most part they are Gen-Z kids who care more about Harry Potter and iPod and boy bands and zilch of saris and history and Carnatic music. I also feel truly bad about your role as a wife and mother – where once you were a self-proclaimed firebrand, now tending house and keeping cows and wistfully hoping your kids somehow recognize the India you once knew.

I wish I could agree or disagree with Carnatic music. But I went back and re-read the posts on this subject (somewhere on this blog), I can’t help agree with the guy’s logic about no innovations for 400 years. No wonder modern kids don’t care very much. Except perhaps the real Indian kids who grow up in Madras maybe.

I really really hope your kids remain close with you as the years go by. They say “maa-beti” bond is very special (can’t be put into words). And for once I wish Mr. NS’ point (about the India stuff kicking in later in life) is true – and somehow kicks in sooner.

Jai Mata Di

You do that RG, if that makes you feel better.

Shoba, with respect, that’s not fair. RG is extending a branch here..

RG – I read your comment before I typed my (original) reply, but I agree with you. I think NS point is right in a way too — kids are kids and they’ll grow up how they’ll grow up. I guess it’s a wishful fantasy that anyone lives abroad for 20 years and finally returns to roots and attempts to transmit culture and tradition to the next generation, and finds out that the things we found beautiful and charming then (20 years ago “then”) are just moments of nostalgia and reflection. I guess this is the evolution of life.

But I think as loyal readers we also have a responsibility to further our cause, so Shoba, is there anything we can do to get your writing etc. back on track? We are sincerely hoping for the “next magnum opus” … so if there’s anything we can do then we’re happy to do it for you.

loyally yours,

VK

Maybe this helps. I try not to /thrust/ stuff upon my teenage daughter, rather try to create conditions for enjoyment and let things take over. I’ve found that kids are motivated by peers and by their own natural abilities and talents – so a music class or tennis classes or stuff like that, where they can learn things together with other children, as well as apply themselves against peers, is what is the best motivation. Solo teaching, unless it is something the kids want themselves (e.g. homework help), usually doesn’t work.

RG – your comments are well placed (hard though it is to admit that). I am puzzled why Shoba, normally well balanced, has responded this way. But perhaps we should all take a break from writing about Shoba and her kids for some time. Sometimes sore points become just sores. Let’s leave it be for some time. Can I buy you and Vinay a beer in the meantime?

NS I agree with both things. FWIW most leadership classes emphasize self-learning and self-directedness … and people generally go where their “inside” tells them, not where parents or elders or teachers tell them. I guess you (NS) and Rajit are best qualified to give parenting advice.

Shoba hope all is well. I second Vaidehi in that success emerges only after failure, and (per Rajit) that experiments have outcomes, not success/failure. Each of the 900 failed light bulbs had an element of learning that drove Edison to finally build one that worked, and now a whole planet is grateful for it. Pick it up, girl, and return to the field. That second book is a-waiting!

Hello all. I’ve been away. RG: I don’t want or like pity, hence my pithy response. Also, I am startled that the message that I am giving out is that the India experiment didn’t work. Maybe it is because I only write about the conflicts. But although you guys think you know my life (fair enough since I write about it), you actually don’t. I don’t talk about the richness of friendships that we have developed here and how my daughter’s kathak has helped her navigate her culture in a wonderful way and how my kids are close they are with grandparents, aunts, uncles. We have a great life here. I just don’t write about much of the positive aspect of it (where is the story in self-satisfaction), which is why I was pissed off by the pity.

Where the pity is well-placed is my difficulty with writing another book. But even there, please I don’t need your pity. Your prayers are welcome though.

Also, I don’t get much value from being on a stand and being interrogated– especially when many of you have made up your minds and are looking for an angle in my answer to substantiate your made-up minds. So I’ve moved the comment section away from where I normally post So please don’t expect regular responses. I’ve tried doing that to all the regulars and the same old questions come up again and again. It doesn’t help me at all. I’ve moved on. So should you.

Shoba, I think I’d posted briefly here (“Wealth”, 3/26/2013), it is good to be back.

I agree with Mr. NS here, that is exactly the strategy we’re using with our kids in San Jose. Find the one or two things (hopefully Indian things) and then once you find the talent, you have to put it through some sort of teaching vehicle that itself propels kids forward. They won’t take to it if it is thrust on them. And they will block it out if one forces it on them.

RG it is hard to disagree with your points. That’s a very sobering fact and conclusion. I actually went back and read RTI book, and now, looking through some of the posts, Shoba, it looks like nearly all your efforts have sort of stalled. Sari wearing, “forced” sari wearing, going to temple/puja, singing Indian songs, whatever else. But, “nearly all” doesn’t necessarily mean “all”. Is there something about India – maybe cooking or some other cultural thing – that your kids have taken to well?

Even if not, I still find your RTI story very valuable in the sense that it is a real life picture of what the ultimate RTI outcome is going to be. Many parents (esp in Bay Area) rightly feel that going back to India surely means their kids will pick up on the Indian stuff. Your book and experience shows us that that is not necessarily true. That is a great (even if sober) revelation – esp for parents who are contemplating such an enormous life-changing move. In fact I would put it right up there with people who are itching to come to the USA – things are not as rosy as they were many years ago, with scarcer visas and fewer jobs and generally poorer prospects.

In that sense your book and life experiences are immensely valuable. So, RG, there’s that.

Shoba I can totally understand your perspective! I live that life now!

I guess to all of you, Vinay and RG and others .. you seem to be all fixated on the question of “did it work”. That is very easy to ask from the point of view of a man, you have a job and your own independent station. Your wives (not sure if they work) don’t have that advantage, and yet you expect they will not only “keep house” but also “give you love”. Remember that marriage is a two way street. You can’t expect your spouses to “make it work” by themselves.

Shoba the other thing I would say is I have a friend, about 10 years older than me, with 10 and 12 year old girls, and she is facing the same thing as you. Her kids have very little interest in Indian cultures and she also finds it very difficult (despite the fact that she did her MS here and works in a bank) to keep up with the 21st century stuff. I guess we women ultimately do have to come back to home and hearth. Someone once wrote about “haldi kumkum feminism”, well I say it takes guts to put on kumkum with style and no man can do that.

Don’t let this get you down Shoba. You have a lot going for you and in a few years time when your children are grown and gone off to college I am sure you will make a comeback. Maybe even earlier.

Neil Jones, a recreational pilot interviewed

by the media said the plane car breakdown cover

maker is completely confident in that solution. This analysis will help you decide which

is best for you. Pros and cons: this is the area which is meant for sitting.

However, the taxi operator round right here is the best option for you.

If you are one of the premier services which are just not the best

option for many people using the airport.