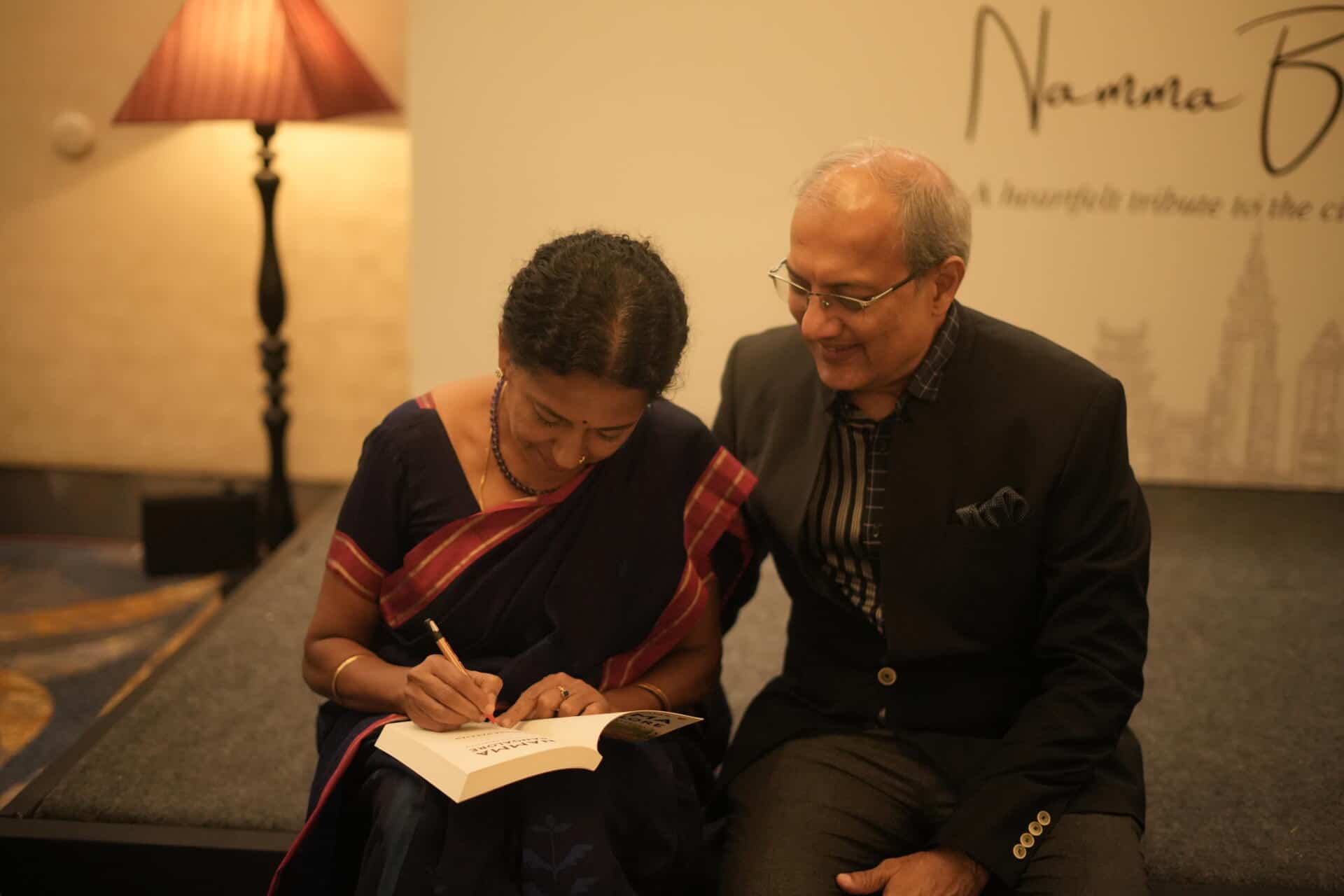

A CONVERSATION WITH SHOBA NARAYAN, AUTHOR AND JOURNALIST

by Annie L. Scholl

After 20 years in the United States, journalist Shoba Narayan and her husband decide to leave their Manhattan home to return to their native South India. They want their children to not only know their aging grandparents and extended family, but also their Indian heritage.

From her home in India, Narayan talks about her memoir, which came out in January, her writing practice, and process:

Q: I’m really grateful to have discovered your delightful book. How did you feel about it being launched into the world?

A: Like a pregnant woman about to give birth. You know, that excited-nervous-restless-anxious feeling. But mostly excited. This book took 10 years to come to fruition. I think it’s time.

Q: Tell me a bit about your writing life up until this point.

A: I have been writing my whole life. I was one of those kids who wrote poetry as a child, angst- ridden journals as a teenager. I began writing for my local newspaper at 18 and never stopped. After I moved to the U.S. for college, I wrote for the Daily Hampshire Gazette in Northampton, Massachusetts. Then I got a master’s degree in journalism from the Columbia (University) journalism program. After that I did freelance work for a number of publications in the U.S. I now write a column for HT Media. I’ve also published one other book in the U.S. It’s about food and my life.

Q: Could you have ever imagined writing such a book?

A: Not at all. I grew up with cows roaming the streets in India, but I think a particular set of circumstances had to come together, almost as if the universe was conspiring to bring them to me, in order for this book to happen.

Q: It’s obvious that you put a lot of time and effort into researching this book. What was most challenging about that process?

A: The cow in India has become so political. At first, I tried to chase down the various political stories that are now epitomized by the cow, but I finally decided to delete all of them and make the book apolitical and therefore, hopefully, timeless. This is really a simple story of two women who love cows.

How is the book being received? What are you most delighted by so far?

So many readers have been so gracious about the book. I am loving it.

My Milk Lady is a charismatic character who emotes well on the page. I was worried that there would be some hate speech, given that the cow is a political animal in India, but thankfully I have seen none. Readers have commented that I have changed the way they view milk women, the urban dairy system, and all things cow.

How has writing the book changed you as a writer?

The bovine is divine in India. I heard this statement all my life and used to roll my eyes. Now, I am not so cynical. The connection that certain animals have with cultures and religions goes back millennia and connects us to our hunter-gatherer ancestors. The sheep is linked to Christianity, the horse to Islam, and the cow to Hinduism. India hasn’t shed itself of this link, which is a cool thing when you think about it.

Tell me about your writing practice. How often do you write? What environment is best for you to write in—your home? Coffee shop? Somewhere else?

You mean, when I am not “doing research” on Instagram? Seriously though, my writing practice amounts to the same pattern: stare at the computer screen. Write a line. Hate it. Rewrite. Repeat. Decide to check if new bird photos have come on Instagram—being a birder, I use Instagram to identify new species of birds. Spend ten happy minutes gazing at new bird photos. Feel guilty. Eat chocolate. Walk away from my study in disgust. Sit at my dining table with paper and pen and write without distraction for as long as I can hold out. I work at home. All over my home. Bedroom, dining room, study….

How do you know when something is meant to be expanded into a book, like this story?

When it has more than one plot line, I guess. This one is like a hub and spoke. In the middle is my milk lady. Radiating outwards are so many elements—cows, animals, India, Hinduism, myth, animal breeding, native cow species. How can it not be a book?

What do you love about writing? What frustrates you?

Writing makes me lose myself, which is why I love it so. Writing well gets progressively harder as you read a lot, which is the frustration.

Q: After reading your book I care about cows now. I want to knock on my neighbor’s door and ask if I can meet his cows. I learned a lot about cows from your book, but also about life and what’s important. What do you hope readers will take from your book—and why should they read it?

A: This is a good question, an important question. If you factor in geography, then the thing to hope for is that your readers will embrace, indeed seek, encounters with people who are different from them. This is possible in every city. So many people you pass every day and interact with superficially all potentially have strange and fantastic lives that you can learn about and enjoy. They have great stories.

Leave A Comment