Most old cultures: Israelis, Russians, Chinese, and certainly Indians are this way. Don’t know enough about Europe’s old cultures to check if they are this way too. When I say West, I mean America. Would be interesting to check if a Polish or old German grandmother says thanks– or not.

How did the word ‘thank you’ evolve?

No need to say thank you, we’ll just even things up later

Notebook

Shoba Narayan

My mother dislikes it when I thank her. She is a youthful 76-year-old woman with grey hair and an easy smile. She makes friends easily. She likes to travel. She talks to strangers and is known for her empathy and compassion. Her emotional quotient (EQ), the new measure of a person that is often pitted against the traditional IQ, in other words, is very high.

My mother knows exactly what to say and to whom. Except that she doesn’t accept thanks from the ones she loves. She screws up her face into an expression of distaste. She looks insulted.

“What thanks? I don’t need your thanks,” she will reply when I thank her for buying my groceries or taking my children to school.

This curt response used to disconcert me, particularly after I returned from America, where I learnt – through magazines and advertisements – that we ought to accept thanks with grace. “Because you are worth it,” said one ad. Magazine articles routinely exhorted me to accept gratitude because I deserved it; to express gratitude fulsomely, no matter who the recipient or the circumstance. “It’s never too late to say thank you or sorry,” said one poster. Except with my mother.

“Thanks, ma.”

“Get out of here. What are you thanking me for?”

Or versions thereof.

This is the difference between the two countries that I have called home. The West views actions as transactions: someone does something for you and you say thanks. The East, particularly India, views actions as extensions of a relationship. It would be insulting for me to thank my grandmother for massaging coconut oil into my hair because such a statement would dilute the intimacy of the act and the relationship.

More important is that you thank someone who is “not you”, who is outside of you. In India, the closer you get to someone, the more you view them as extensions of yourself. Thanking them would be like thanking yourself. Who does that? Hence my mother’s umbrage when I express gratitude verbally. In her world view, you do things for your loved ones without fuss, without much talk. And they do something right back. So, when I thank my parents, I am making them outsiders.

It is a cultural thing; but it is also a generational thing. Most Indians of the previous generation use the word “thanks” sparingly. Offer a seat to the grandmother on a train and she will smile gratefully for sure. Half an hour later, she will open her snack box and offer you the tastiest morsel. It is her way of acknowledging what you did for her.

“Words are cheap,” says my mother. “Why should a daughter thank a mother for doing the things that a mother does?”

I thought it was just my Mom. Recently, I was in Kanpur, a small town in the Hindi heartland of India. The couple that invited me were extraordinarily kind and generous. They also bristled when I tried to stammer out a thanks at the end of my visit. “What are you saying?” the lady interrupted, snuffing out what they deemed was my “angrez” (English) affectation. As I left, in lieu of thanks, she simply said: “Blessings.”

It has taken me seven years to get used to this. Perhaps it has to do with my personality. By nature, I am a somewhat formal person. I thank everyone for everything – including my husband – because I believe words are an extension of how you feel.

When I feel grateful, I know of no other way to express it than to say thanks. My method is unimaginative, according to the Indian way. It is also empty. Saying thanks is quick and lazy. Indians of my mother’s generation do it much more imaginatively. They keep a long tally of scores and come up with creative ways to settle them.

“You know, Reena took me on that trip to that safari park,” my mother will say. “I should just give her this jungle-patterned jewellery set for her next birthday. I am not going to wear it and it will remind her of that trip we took together.”

I have neither time nor imagination to do this sort of mental tally morphed into imaginative return-gifts. So I take the easy way out.

“Thanks, Ma,” I yell as I drive out of the house.

I laugh over her scolding.

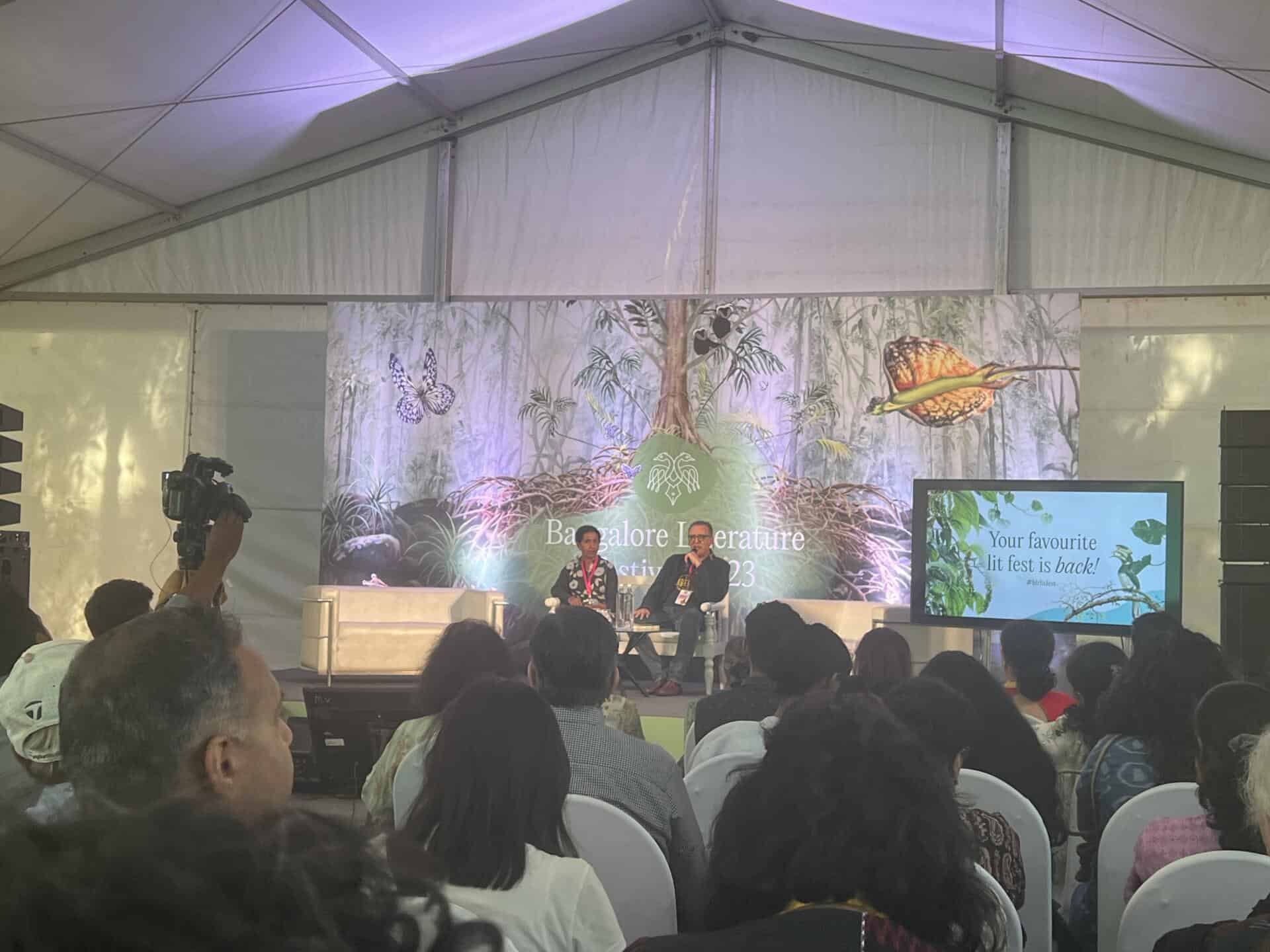

Shoba Narayan is the author of the memoir, Return to India

Fascinating, “West views actions as transactions”. If you have called New York your home I am not sure how you’d have ever come to that conclusion. Remember that the brave firefighters and cops who ran into a burning building some 10-12 years ago did not do a “transaction”. I don’t know who you hung out with, but as a lifelong New Yorker I can confirm that neither I nor anyone in my community goes around “thank you” to parents and close relatives for every little thing.

I find it fascinating that so many Indians have this distorted “East is more family oriented; West is more transaction oriented” viewpoint. You’ve quoted Wendy Doniger and others. Just remember that while the liberal intelligentsia frequently pops up the “divorce rate” statistics (for the West) but the very same people conveniently ignore the unnumbered killings of female fetuses, rapes (that are not reported) and other domestic violence in the name of dowry and caste and religion that happen every day in India. You can’t speak of family values in India when the same family values permit (and indeed encourage) “honor killings”.

I can’t fathom how any responsible journalist can still hold such divisive views.

Dear Laura:

Bravo on calling me out in a nice way. Thanks for your email.

I love New York so I hear ya. I was in NYC during 9/11 so I know exactly what you are saying about the firefighters. But I see that as the spirit of volunteerism, which NYC has in spades.

I think what I am not making clear in this short piece is the spirit of volunteerism versus the sense of family. I see running into a flaming building as an act of volunteerism, which India woefully lacks (okay, now all my NGO friends will disagree with this).

I disagree with you about the West always saying ‘thank you’ but that is a small point. All my friends :) always said thank you to their folks– for every small thing. In America, it is almost reflexive to end emails with a ‘thanks.’ Here, they sign off with anything ranging from ‘Shubamasthu” to ‘Affly.’ So go figure.

I think the point you make in paragraph two is spot on and worth remembering. I am research maternal mortality rates and educating the girl child. As a feminist, everything that you say in graf two resonates.

But, Laura. In opens, you have to make some sort of larger point, aka generalization. And my generalization, gross as it is, is that Indians go out of their way for family and ignore the world outside. In America people put out for family and community. Sometimes, Americans can’t stand their families but they will still put out for community. In India, there is this reflexive family focus in good and bad ways. Fathers will save and spirit their sons who have driven drunk and killed people (this is a fact). These is the dark side of ‘family oriented’ as you call it.

So I stand by my larger point, but take your feedback that it is not the whole truth; and paints a simpler/rosier picture depending on your point of view.

Thanks for calling me out. Will be careful next time.