The wisdom of collaborative consumption

European cities such as London have come up with bike-sharing programmes subsidised by advertisements.

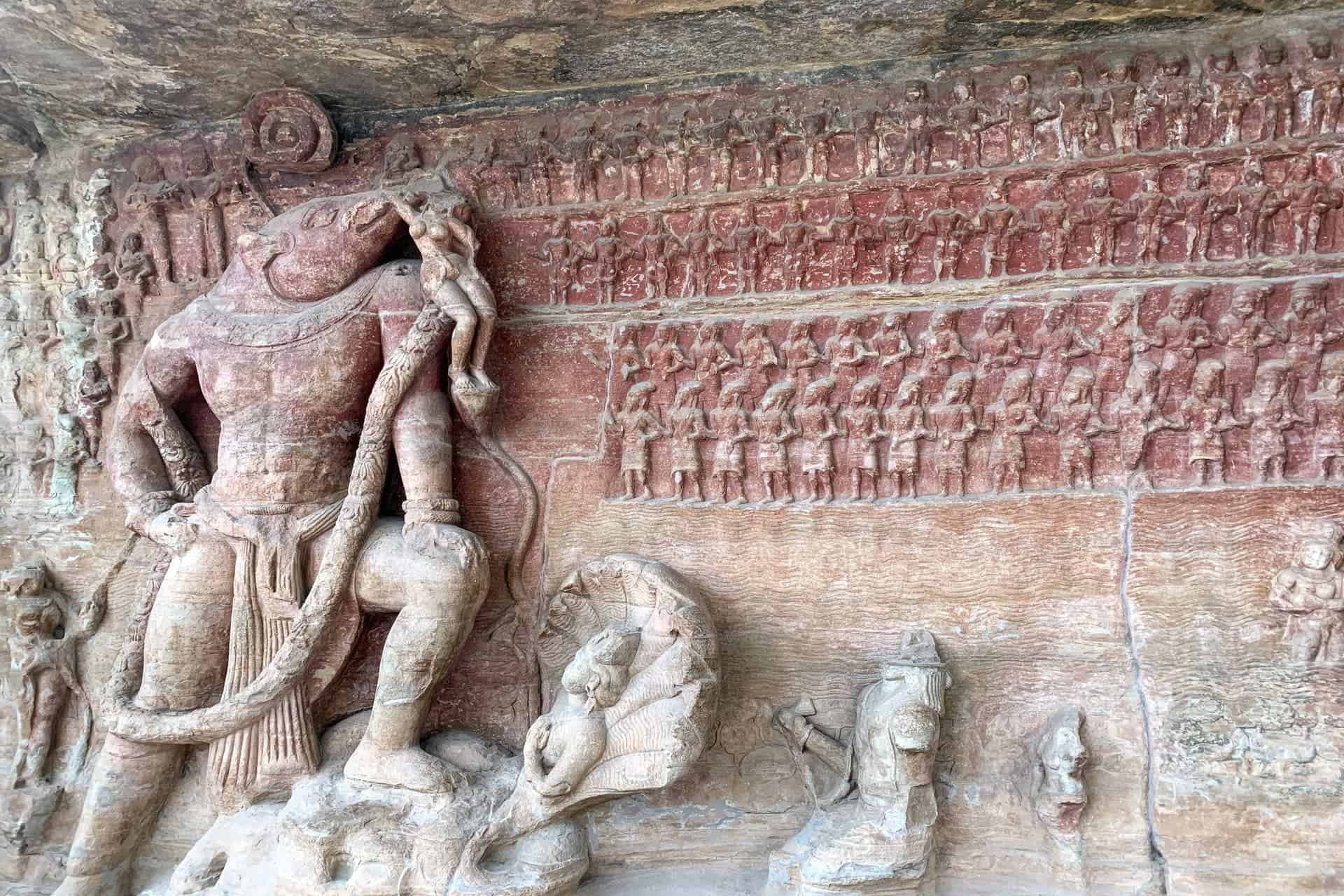

BLOOMBERG

Have you ever opened your wardrobe and discovered it is full of clothes but you have nothing to wear?

Economists have a term for this. They call it depreciating value of assets and there are several methods, “straight-line” and complicated, to calculate the depreciation of vehicles or electronic goods.

The psychological reason behind depreciating value has to do with the old biblical injunction against coveting. We all covet things we don’t own, but the minute we acquire the object of our desire, it begins to lose its value.

The Cavalli gown that looked stunning on the mannequin in the shop window looks dreary inside your closet. That additional Nikon lens that cost a month’s salary now seems extraneous on a camera that already performs well.

Collaborative consumption might be the answer. The premise behind this concept is as old as barter economies. Trading a cow for a buffalo, jointly using the village water well, Egyptian homes built around a common courtyard where women gathered to dry spices and children gathered to play – all are examples of shared resources in ancient cultures.

In the past two decades, old-fashioned sharing has morphed into successful rental businesses: witness the success of Netflix, Zipcar and CouchSurfing. Rentals give people the advantages of ownership without its accompanying burdens.

Thanks in part to the global financial downturn, and as a reaction to the excesses of the past decade, this trend is slated to become a groundswell in the coming 10 years.

As the social innovator Rachel Botsman and the serial entrepreneur Roo Rogers point out in their book What’s Mine Is Yours: the Rise of Collaborative Consumption, networked technologies and peer-to-peer marketplaces will enable a “rapid explosion in swapping, sharing, bartering, trading and renting … on a scale never possible before”.

The population of the world will increase by 50 per cent from 6 billion to 9 billion by 2050. For each person to continue to consume the same amount of resources is unsustainable. The world has to come up with ways to spread resources among many people.

Rapid mass transit is a great example of collaborative consumption but it needs to trickle down further into mind-sets.

Several European cities including London, Lyon, Stockholm, Barcelona and Oslo have come up with bike-sharing programmes subsidised by companies that advertise on bikes that commuters can hire or borrow to ride short distances within the city, using different payment plans. Infosys Technologies in India has free bikes that employees can use to get from building to building in its sprawling campus instead of using cars.

Most IT companies in Bangalore use private buses to transport employees to and from their large campuses in Electronic City, thus reducing the number of cars on Bangalore’s already choked roads.

Netjets, owned by the US billionaire investor Warren Buffett, is an example of reducing idling resources by sharing the same asset with several (very rich) people.

Freecycle is a grass-roots global network in which people exchange things they don’t need with others who want their discarded items.

There are two Freecycle groups in the UAE – one in Dubai with 873 members and one in Abu Dhabi with 375 members. Such a group doesn’t exist in Bangalore, where I live, so perhaps I will have to start one.

For collaborative consumption to work, the assets have to conform to certain parameters. Use cannot be heavy or consistent. The vacation villas that a number of Bollywood stars seem to have bought in the UAE, for instance, would be ideal for collaborative consumption.

Rather than build new hotels and then run the risk of having empty rooms later in an economic downturn, some enterprising social entrepreneur could come up with a nifty website that rents out all of the empty villas in the Middle East to vacationers. Such models already exist in Italy and France but are yet to make inroads in the region.

Companies such as Bag Borrow or Steal, which rent designer handbags, watches and jewellery, would be a natural fit for countries such as China, Japan and the Gulf states, where women buy a lot of luxury designer goods that then sit idle in their closets.

Even if a woman of stature cannot bear the thought of renting out her things, she can share informally with an extensive network of nieces or cousins in exchange for simple chores.

How many of you have watches, ties or designer suits that you have never worn but cannot bear to throw out because they cost a lot? Such discretionary goods are ideal assets for collaborative consumption. Objects that we use frequently, on the other hand, are not suitable for sharing: iPads, sunglasses and cameras, for instance.

The micro-lending model involves more than a dozen women pooling money. A similar model can be adopted in which a dozen or so women pool together to buy a Hermes Birkin bag that they can share. Or members of a golf club can share their clubs.

The biggest challenge of collaborative consumption is streamlining operations. What if all the women want the same handbag during wedding season? What if all the renters want the Gulf-facing villa during Christmas? How do you share golf clubs during tournaments, and what if you want to take them for several days during vacations?

Rental businesses have come up with blackout dates and adding extra charges for peak times. In the real world, we have to talk, either in person or through social networks to sort out the logistics.

In an ever-connected world with dwindling resources, we have no choice but to collaborate with neighbours and even strangers to spread the wealth. It is not only good taste. Increasingly it is beginning to make good sense.

Shoba Narayan is a writer based in Bangalore and is the author ofMonsoon Diary

Leave A Comment