The Pride of Gujarat: Aramness Gir

A game-changing safari lodge in India’s wild west offers lion-spotting and luxury in equal measure.

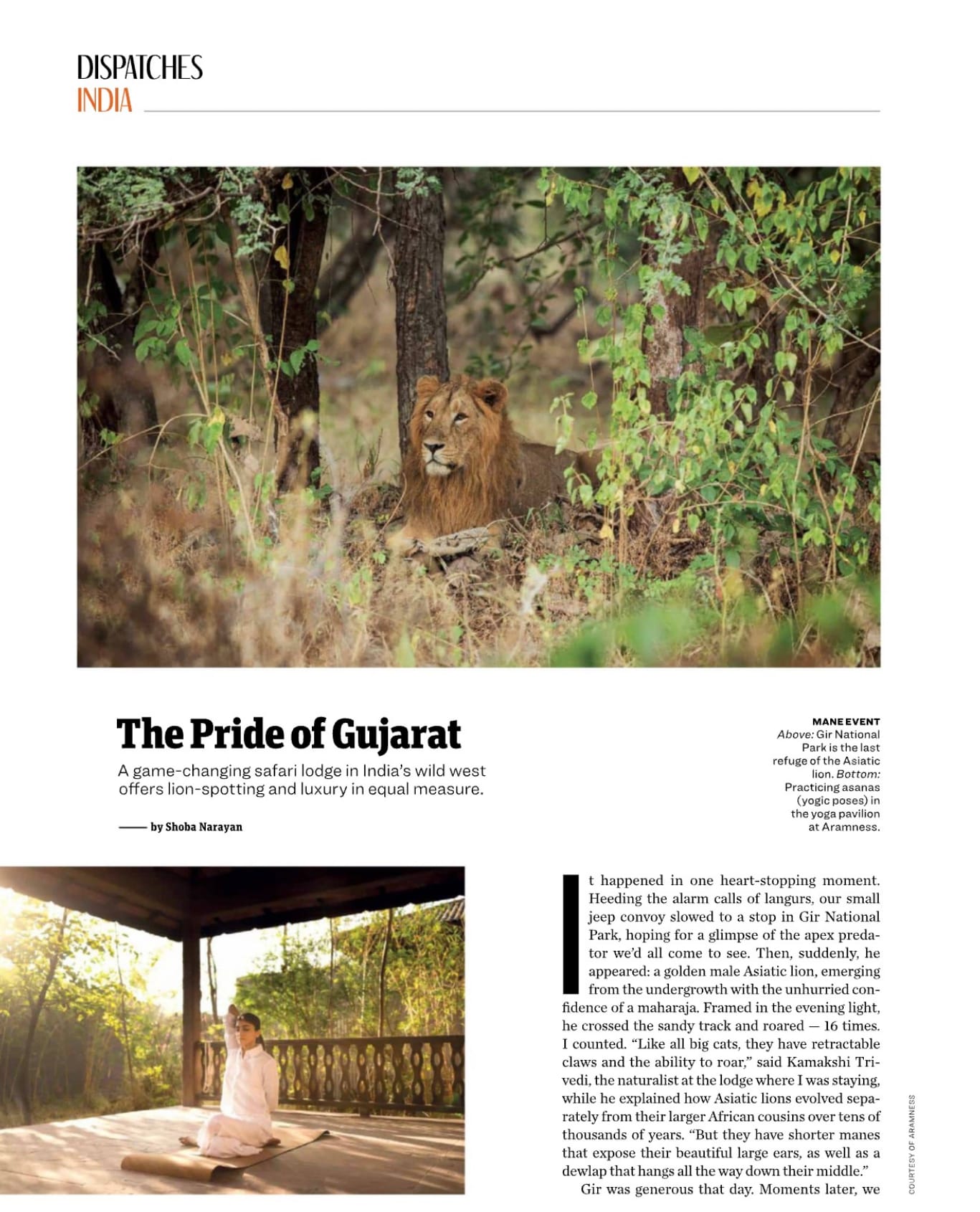

It happened in one heart-stopping moment. Heeding the alarm calls of langurs, our small jeep convoy paused in Gir National Park, hoping for a glimpse of the apex predator we’d all come to see. Then, suddenly, he appeared: a golden male Asiatic lion, emerging from the undergrowth with the unhurried confidence of a maharajah. Framed in the evening light, he crossed the sandy track and roared — 16 times. I counted. “Like all big cats, the Asiatic lion has retractable claws and the ability to roar,” said Kamakshi Trivedi, the naturalist from the lodge where I was staying, explaining how Asiatic lions evolved separately from their larger African cousins over tens of thousands of years. “But they have shorter manes that expose their beautiful large ears, as well as a dewlap that hangs all the way down their middle.”

Gir was generous that day. Moments later, we came upon a young lioness lying on the side of the track. Her mate lay yawning under the banyan tree ahead. We watched, spellbound, for many magical minutes before moving on through a patchwork of scrubland and deciduous woods.

For Indians, the jungle is the original storybook — the stage where our epics unfolded. Both the Ramayana and the Mahabharata sent their heroes to the forest, a space at once sacred and transformative. It is perhaps why, the forest for us, to this day, is a mythic call, in spite of the cameras we tote.

In South India, where I live, we have tigers, leopards, and elephants. But to see lions in the wild, you must travel to the western state of Gujarat. This is final refuge of the Asiatic lion, which once ranged from eastern Turkey through Persia, Pakistan, and central India. Today, Gir National Park and its surrounding habitats on Gujarat’s Kathiawar peninsula are home to the last of them: 891, according to the most recent census.

And that’s how I found myself in Gir one weekend just before Diwali, chasing not just lions, but also the stillness that city life had drained out of me. My base was the area’s newest and most luxurious safari lodge, Aramness. Designed by Johannesburg-based Fox Browne Creative and Nicholas Plewman Architects — the names behind some of the world’s most soulful wilderness retreats, including Rwanda’s Bisate Lodge and andBeyond Ngala Tented Camp in South Africa — the five-hectare property sits surrounded by teak forests and grasslands at the edge of the park, with just 18 two-story villas (each with a small swimming pool and shaded courtyard) laid out in the style of a Gujarati village beyond a haveli-inspired reception building.

Design elements are rooted in the land. White stucco walls glitter with lippan mirror-work from the neighboring region of Kutch, accented by an earthy palette of bone, saffron, and oxblood. Antique carved doors from abandoned houses have been used in the main lobby; discarded wood block-printing tiles are embedded in bar counters. Old railway trolleys have become luggage carriers. Some features are a marvel of engineering. The sandstone jaali screens seen throughout the property are hand-carved in patterns that recall the veins of dried teak leaves that carpet the surrounding forest. Stunning too are the villas’ Makrana marble washbasins, bookended with lion’s head finials. Just getting them here from Rajasthan must have required a degree of will power, or madness, given the state of Indian roads.

I also enjoyed browsing Aramness’s library with its wunderkammer of curios: fraying Gujarati ledgers and rare first-edition storybooks; wooden cowbells once used by the local semi-nomadic Maldhari cattle herders; even kitschy Air India maharaja figurines. This is Gujarat reimagined, which makes the lodge’s name feel almost quixotic. “Aramness,” I thought, sounded oddly Anglicized — until I learned what it really meant.

What does a guest do between safaris? At most lodges, the answer simple: wait. Aramness decided to change that, creating a wellness program to attract guests during the summer monsoon, when Gir is closed.

For luxury lodges – in India, and perhaps all over the world – a vexing question is what to do with guests during the “in-betweens.” In India, some safari parks close during the heat of the summer, from June through October. Sometimes guests who are avid wildlifers come in multi-generational groups where the parents or spouses don’t want to go on safaris, finding the bumpy rides tiresome and tiring. Aramness is creating a wellness program for exactly this reason.

On my first morning, I met Dr. Rafeek Jabbar, an Ayurvedic physician whose office is a bamboo pavilion threaded with birdsong. He felt my pulse, examined my tongue, and declared me a restless Vata type, prone to insomnia and wandering thoughts. Both true. As medicine, he prescribed sound healing, meditation lessons, and a tea made with magnesium-rich bananas to soothe my nerves. The latter, spiked with Indian spices, was delicious — and sent me blissfully to sleep each night.

The next morning, resident yoga teacher Kunal Gawade led my sound-bath session using Tibetan singing bowls, crystal bells placed on chakra points, and softly resonant drums. Even for someone like me — who, as my husband likes to say, has tried every “woo-woo” practice on earth — it turned out to be one of the most profoundly healing experiences I’ve ever had. I booked a second session the following day. Aramness’s InBody scanner later revealed I needed to lose eight kilos, hard to do when faced with a tasty Gujarati thali at dinner. Thankfully, the fluffy bajra roti flatbreads made by local chef Halumaben were low-carb and gluten-free, so I dug in.

Around 60 percent of the staff come from nearby villages. On my last evening, I visited the closest of them, Sangodra village, where I was invited into the home of a Maldhari family. For generations, these pastoralists have inhabited the forests of Gir, coexisting with its bevy of wildlife, which includes leopards, nilgai antelopes, and wild boar. Each household owns between 20 to 100 buffaloes and cows that they herd through the jungle. If a lion attacks and kills one of their animals, they bear no rancor. Instead, they call it a “forest tax.”

In the 1970s, as India began instituting wildlife sanctuaries, the government began relocating Maldhari families to settlements on the forest’s perimeter, but as Ramuben, the elegant matriarch of this household, told me, it wasn’t the same. “We miss our ness [hamlet] in the forest,” she said. Then the penny dropped. Aram means “relaxation” in Gujarati; ness is a forest home. Aramness — the name makes perfect sense.

In a world obsessed with speed, Aramness instigates slowness. It is a nudge that comes from the design, the staff, and indeed the food. When the forest becomes part of the spa experience, or vice versa, the real therapy isn’t the lavender massage oils or the citrus-spiked herbal teas. It is an act of remembering what stillness feels like. It is observing wild boars root out tubers from the earth while swimming in the natural plunge pool behind your villa. It is listening to cicadas and cuckoos as dusk falls, to watch fireflies dance as you return from the evening safari, to look at the smiling eyes of the lodge staff who stand outside to welcome you with cold towels. And to realize that somewhere out there, the maharaja of the jungle prowls.

Details

Prices:

Single villa/kothi US$1000 for 2 adults per night plus one safari.

Family villa/kothi US$1300 per night for 4 adults. This has two bedrooms and a living room.

Very interesting read! You write wonderfully, Shobhaji!