‘Hinduism, like many great religions, is about feasting and fasting, praying and eating prasadam’

Shoba Narayan’s new book delves into the many ways food and belief are intertwined with our identities

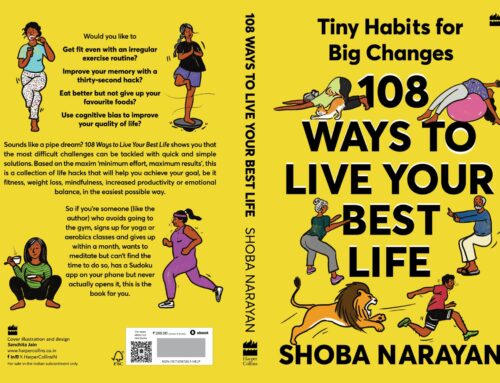

“In no other culture does faith play out in as colourful and traditional a fashion as in India. In our country’s places of worship, we find rich myths, ancient traditions, cultural touchstones and delicious food that are offered to the Gods and to humans.” According to award-winning author and columnist Shoba Narayan, her newest book, Food and Faith: A Pilgrim’s Journey Through India (HarperCollins Publishers India) began as a food book before it morphed into one on faith.

“Food & Faith explores this rich tapestry that is the hallmark of Indian culture. I was humbled and privileged to visit many temples and talk to priests and scholars. Through their stories and through my visits, I discovered how food and faith form a timeless and profound connection.”

Hopping across the length and breadth of India’s many places of worship, Narayan’s new tome delves into the many ways food and belief are intertwined with our identities.

Excerpted from the chapter ‘Udupi: The Boy Who Stole Butter’

SEEKING AND FINDING COMFORT IN THE COCOON THAT IS A HINDU TEMPLE

It is 11 am, and the granite floors and pillars offer cool respite from the heat outside. Devotees line up quietly, muttering prayers, hands clasped together fervently. It is a scene familiar to anyone who has visited a temple in India. Swishing saris, the smell of sandal and incense, topless Brahmin priests hurrying between idol and devotee, clanging bells, chanting men and women. For the faithful, Hindu temples inspire devotion, hope and a preternatural peace that descends in spite of the surrounding chaos, as if generations of muttered prayers have muted the soul into peaceful surrender.

The Krishna temple in Udupi is no different. It isn’t very crowded on that June morning. My mother and I are pretty much left alone to pray in peace. We walk around the sanctum sanctorum many times and peer at the idol. No hustling priests, no crushing crowds, no furtive glances suggesting a small donation for closer access to the deity. It is just us in quiet communion with the lord.

In one corner, a group of ladies sit in a circle, singing Krishna songs and stringing garlands with lightning fingers. They have separated yellow marigolds from green tulsi leaves, jasmine from tuberose and each woman takes a flower or leaf to string together or alternately. Several string fragrant jasmine flowers—Jasminum sambac or what we call gundu-malli in South India—in garlands. In the opposite corner, a visiting group spreads out their tanpuras and dholaks before commencing a spirited Krishna bhajan.

Near the temple tank, one of the hubs of activity, there are men in dhotis bathing, praying and performing rituals. One monk, clad in saffron robes, sits by himself, singing a bhajan that is remarkably soothing.

My mother and I sit leaning against the pillars, listening to bhajan mixing with folk song, breathing in incense mixing with the smells of jasmine and coconut, watching idly the run-off stream of milk and honey and holy water that is used to bathe the idol every morning. After a while, my mother repeats the phrase that countless others say after their communion with God.

‘Let’s go eat.’

UDUPI’S PRASADAM

Hinduism, like many great religions, is about feasting and fasting, praying and, it must be said, eating prasadam. The Udupi temple is part of the famed pilgrim’s triumvirate of Udupi-Sringeri- Dharmasthala, all of which serve very good food to thronging devotees. Udupi’s temple food is the best, the faithful tell me. We walk out and turn left to the feeding halls, my mother leading me with the expertise of having spent a lifetime visiting temples.

Indians are funny that way. The elderly in China play mah-jong. American senior citizens go on cruises and play golf. Europeans visit museums, tour wineries and dine at Michelin-star restaurants. Indian elders visit temples. Pilgrimages are a big part of their lives, as I see daily with my septuagenarian aunts and uncles, not to mention my mother. For her latest birthday, I offered my mother the choice between a two-week trip through Europe or a week through interior Maharashtra to visit one of the twelve jyotirlingam shrines to Lord Shiva. She chose Shiva over the Sistine Chapel.

Udupi is part of my mother’s regular beat since the Mookambika Temple of Kollur (which happens to be our family deity) is in the same area. She has been visiting the temple twice annually for the past twenty years. En route to her devi, she usually stops to see Krishna.

So we hurry, mom and I, down the corridor, to the feeding area. ‘The Brahmins are fed separately. Upstairs,’ my mother says.

I wince.

GUILT AND SOLACE

Let me just come right out and say it. Although I grew up in a devout Hindu family, I am uneasy about my religion—about all religions for that matter—for all the usual reasons. Faith gives solace, for sure, but it also inspires guilt. Religion brings people together, but also divides them. It gives peace and causes war; it hurts and heals. Since I come from a fairly traditional, devout, Tamil Brahmin family, I don’t express my antipathy very much. Instead I disengage, to the extent that it is possible, in a religious family such as mine.

I follow my mother up the stairs to the separate area where we, as Brahmins, will be fed. ‘What about “in the eyes of God, all are equal”?,’ I feel like asking my mother, but she is racing up the stairs.

The hall is huge, and people are sitting cross-legged on the floor. Young, good-looking boys exuding what my mother calls tejas, or radiance, stride through the hall carrying giant containers holding rice, rasam, vegetables, sweets and ghee. We take our places. Banana leaves are placed before us. Then a veritable feast with all the regional delicacies appears. There are spicy pakoras, sweet payasams, brinjal gojjus, jackfruit curry, several chutneys, kosambari salads and a mound of rice in the centre.

A priest walks down the corridor. With his fair skin and a bright red vermilion dot in the centre of his forehead, he looks resplendent in a purple silk dhoti. Behind him are a line of young ascetics. I stretch my upturned palm like the rest of the congregation. The chief priest pours a little holy water into my palm, which I assume is to wash my hand.

‘Drink it,’ my mother hisses.

So I do, wondering if the water is safe.

‘Govinda,’ says my neighbour, uttering one of the many names of Krishna, this one meaning ‘the one who protects cows’. ‘Govinda,’ I repeat obediently.

Govinda is one of the names of Vishnu. The Vishnu names I know by heart are the twelve that my grandfather used to recite while doing his sandhya vandanam or evening prayer. They are:

1. Keshava: The one with long, matted locks.

2. Narayana: The one who gives refuge.

3. Madhava: The one who gives knowledge.

4. Govinda: The one who knows and cares for cows.

5. Vishnave: The protector in the Divine Trinity.

6. Madhusudhana: The killer of the demon Madhu.

7. Trivikrama: The one who lifted his legs so he could conquer the three worlds—heaven, earth and the underworld.

8. Vamana: An avatar of Vishnu.

9. Shridhara: The beautiful lord of love.

10. Rishikesha: The master of senses.

11. Padmanabha: The one whose navel is shaped like a lotus.

12. Damodhara: The one who had a cord tied around his waist as a child.

Each name has a story behind it—of battles fought, demons subdued, benediction given, wisdom dispensed, compassion offered and devotees charmed.

The food is delicious. Barring the jackfruit curry, which must be an acquired taste, I polish it all up. Udupi is justly famous for its rasam, and this one doesn’t disappoint—piquant with a lovely spicy, lemony flavour. I take a second serving of the rasam, then a third.

A young boy comes and distributes Rs10 bills to all of us as dakshina or fee for eating the meal.

We end the meal as we began it: with holy water poured on our upturned palms.

TAKEAWAY

After I returned from Udupi, I decided to do two things. Both involved denial. Once a fortnight, on Ekadashi (the eleventh day of the waxing and waning fortnight), I would fast. This meant not eating anything and drinking just water through the day. Oh, and napping a lot. I did this for a year regularly, and continue to do it intermittently.

The trick is to make religion an ally instead of rebelling against it. If fasting on Ekadashi gave me good karma, fine. But shedding a few pounds was a more immediate goal.

The second was to eat seasonally, which in today’s world meant not eating certain foods, even though they were available in the supermarket because they were wrapped in polythene and were clearly imported from Thailand. Frankly, I am not sure of the benefits of seasonal eating. I am not even sure that the seasonal fruits and vegetables that I consciously choose taste better than the dragon fruit imported from Thailand, the New Zealand apples, Malta oranges or Washington cherries. But if such a practice is good enough for a community that gave rise to one of Hinduism’s greatest philosophers and the creators of the iconic masala dosa, it is good enough for me.

So I persisted—and still do—with my banana stems, young jackfruit, seasonal greens and tender peas, but only when they are in season, cheaply and abundantly available.

Let me see if this turns me into an enlightened soul. For now, I’ll simply settle for a lightened body.

Extracted with permission from Food and Faith: A Pilgrim’s Journey Through India by Shoba Narayan published by HarperCollins Publishers India.

Leave A Comment