All Photos Credited to Ravichandran N. of The Hindu

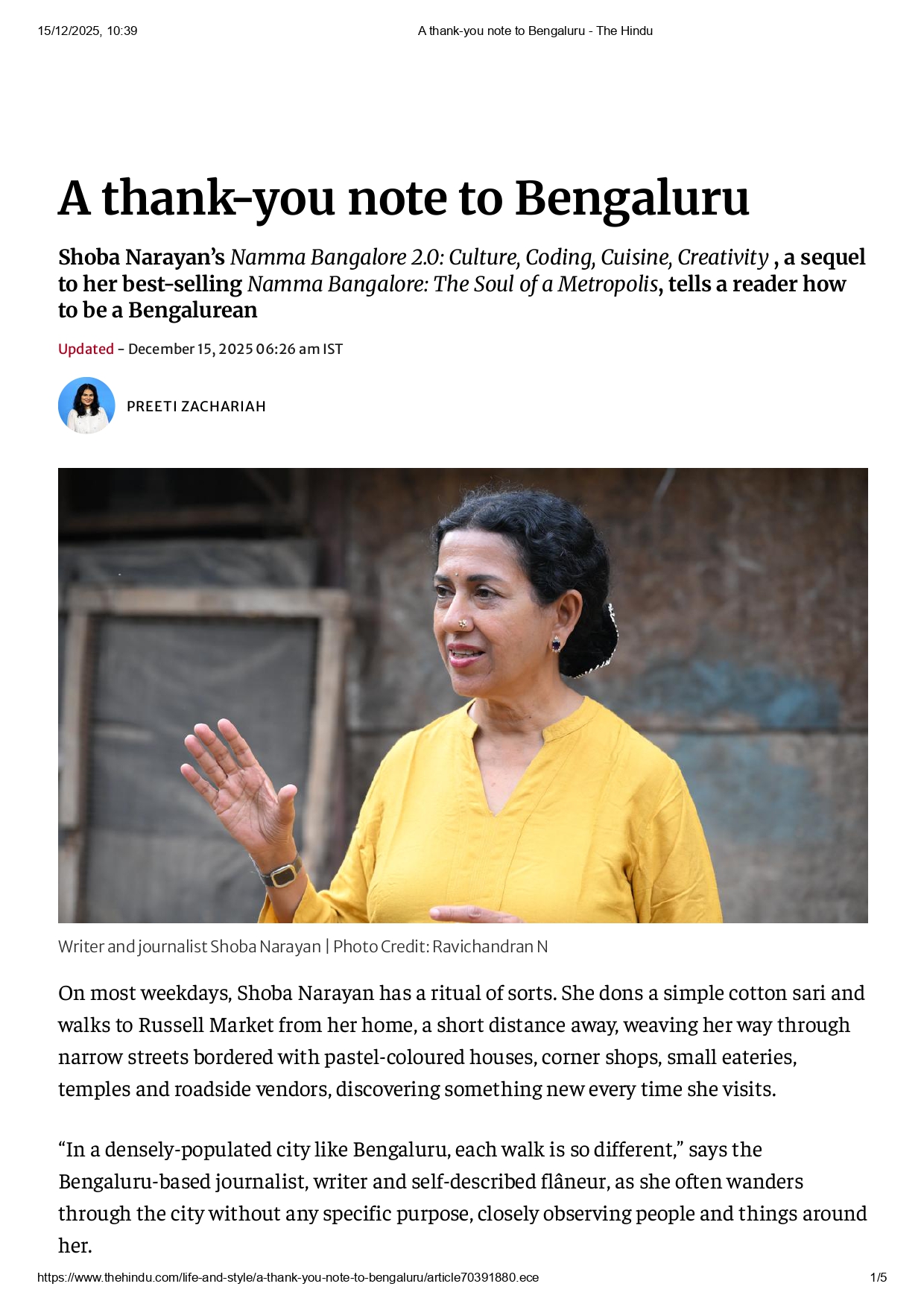

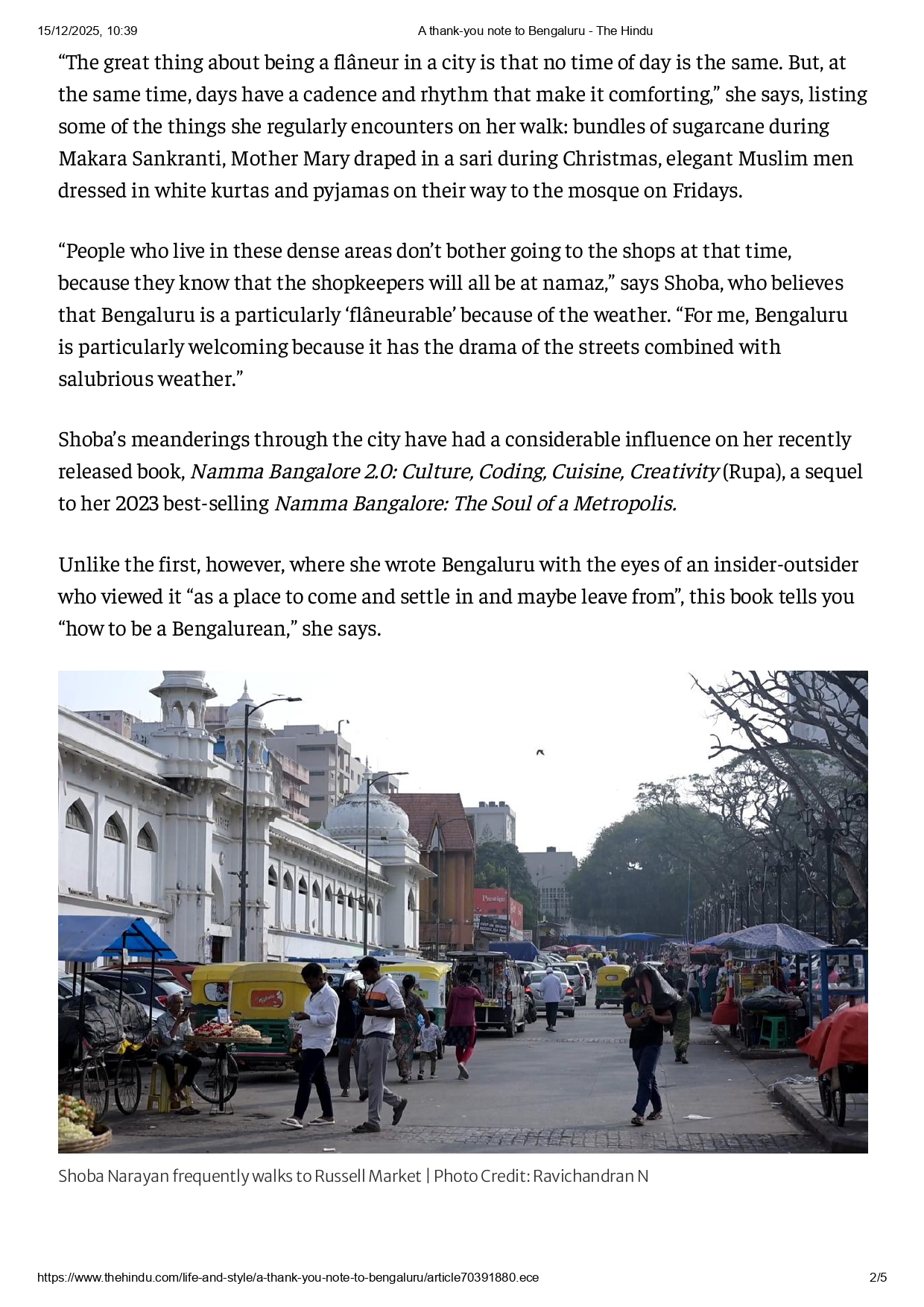

On most weekdays, Shoba Narayan has a ritual of sorts. She dons a simple cotton sari and walks to Russell Market from her home, a short distance away, weaving her way through narrow streets bordered with pastel-coloured houses, corner shops, small eateries, temples and roadside vendors, discovering something new every time she visits. “In a densely-populated city like Bengaluru, each walk is so different,” says the Bengaluru-based journalist, writer and self-described flâneur, as she often wanders through the city without any specific purpose, closely observing people and things around her.

“The great thing about being a flâneur in a city is that no time of day is the same. But, at the same time, days have a cadence and rhythm that make it comforting,” she says, listing some of the things she regularly encounters on her walk: bundles of sugarcane during Makara Sankranti, Mother Mary draped in a sari during Christmas, elegant Muslim men dressed in white kurtas and pyjamas on their way to the mosque on Fridays. “People who live in these dense areas don’t bother going to the shops at that time, because they know that the shopkeepers will all be at namaz,” says Shoba, who believes that Bengaluru is a particularly ‘flâneurable’ because of the weather. “For me, Bengaluru is particularly welcoming because it has the drama of the streets combined withsalubrious weather.”

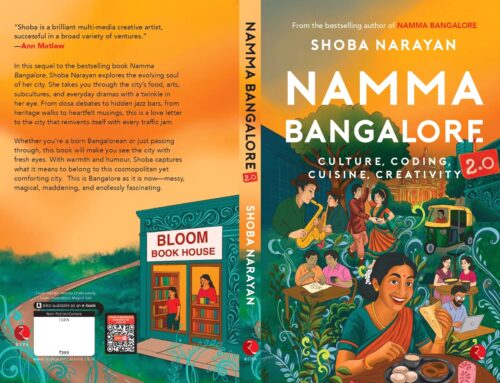

Shoba’s meanderings through the city have had a considerable influence on her recently released book, Namma Bangalore 2.0: Culture, Coding, Cuisine, Creativity (Rupa), a sequel to her 2023 best-selling Namma Bangalore: The Soul of a Metropolis.

Unlike the first, however, where she wrote Bengaluru with the eyes of an insider-outsider who viewed it “as a place to come and settle in and maybe leave from”, this book tells you “how to be a Bengalurean,” she says.

According to her, this emerged out of feeling settled in Bengaluru and “realising that I’m not going back to Chennai again. It also came from a place of making peace with the place that I now call home, and which my children have grown up in,” says Shoba.

The discussion about how the book could be different in tone from her earlier book on Bengaluru also came up in her conversation with her editor, Dibakar Ghosh, at Rupa Publications. “We basically agreed that it had to be written from a point of view of somebody who is now a Bangalorean, so the tonality changed,” she says, adding that while the first book was written for tourists, this one is written for Bengalureans. “It is a book by a person who loves the city for people who love the city.”

In her book, Shoba constantly reiterates what she thinks makes the city so unique, refusing to reduce the “Silicon Valley of India” moniker, which has been thrust upon it and often overshadows everything else it offers.

Namma Bangalore 2.0, which takes its readers on a romp through Bengaluru’s subcultures, regional cuisines, local festivals, and bazaars, offers insights into an eclectic range of topics, whether it be on regional foods like benne dosas, sabakki idlis and Kodagu horse gram soup, the bar and pandal hopping scene in Bengaluru or Karnataka’s folk arts, theatre and hubbas.

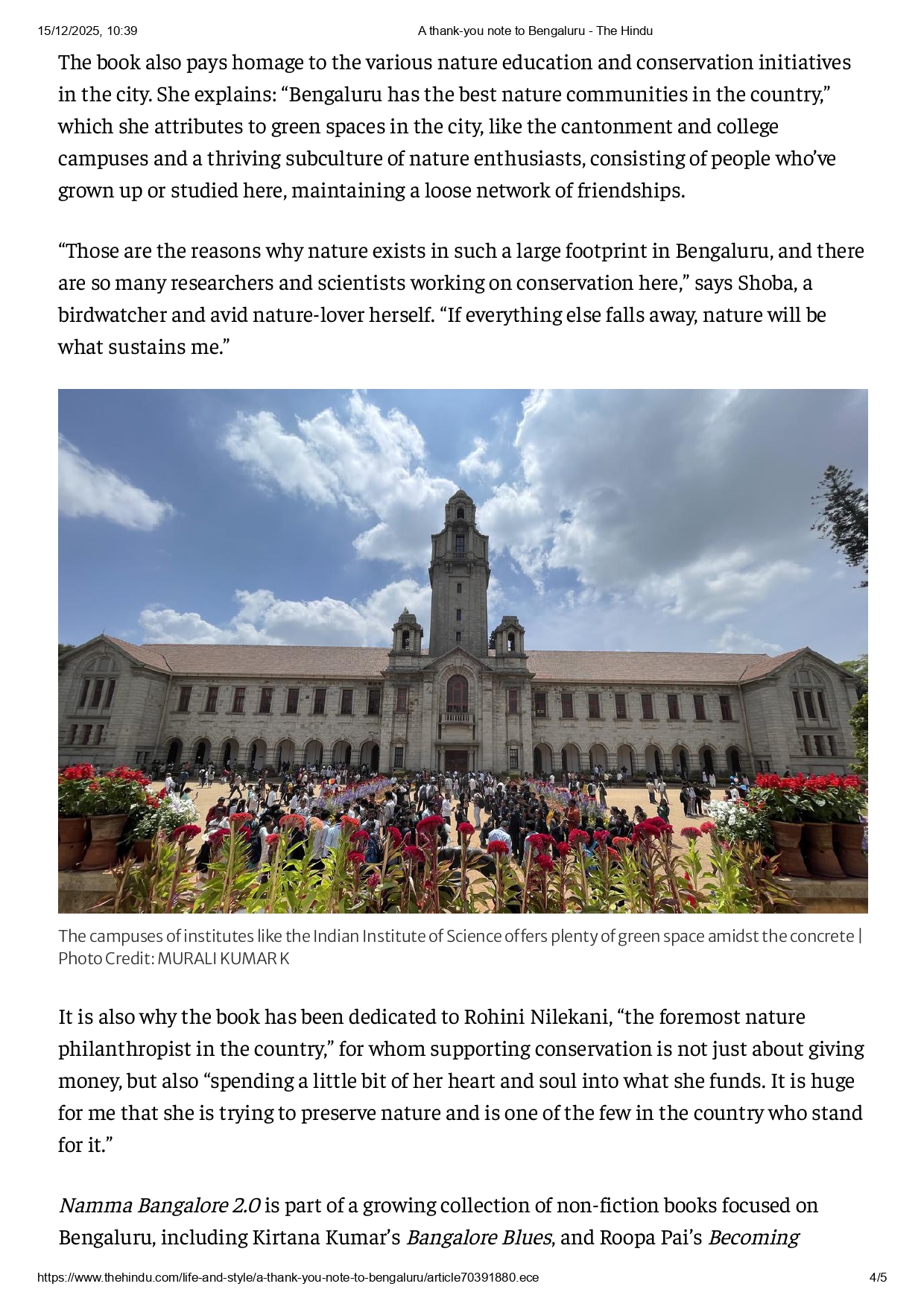

The book also pays homage to the various nature education and conservation initiatives in the city. She explains: “Bengaluru has the best nature communities in the country,” which she attributes to green spaces in the city, like the cantonment and college campuses and a thriving subculture of nature enthusiasts, consisting of people who’ve grown up or studied here, maintaining a loose network of friendships.

“Those are the reasons why nature exists in such a large footprint in Bengaluru, and there are so many researchers and scientists working on conservation here,” says Shoba, a birdwatcher and avid nature-lover herself. “If everything else falls away, nature will be what sustains me.”

It is also why the book has been dedicated to Rohini Nilekani, “the foremost nature philanthropist in the country,” for whom supporting conservation is not just about giving money, but also “spending a little bit of her heart and soul into what she funds. It is huge for me that she is trying to preserve nature and is one of the few in the country who stand for it.”

Namma Bangalore 2.0 is part of a growing collection of non-fiction books focused on Bengaluru, including Kirtana Kumar’s Bangalore Blues, and Roopa Pai’s Becoming Bangalore, besides an updated version of M Fazlul Hasan’s classic Bangalore Through the Centuries, re-published by leading Bengaluru-based architect Naresh Narasimhan “There is a flowering of writing happening in Bengaluru in the non-fiction arena,” agrees Shoba, who firmly believes that the city deserves this. “I think every author who writes about Bengaluru feels that it is a love letter to the city, and I am not the only one.” For Shoba, Namma Bangalore 2.0 was more than just that. “It is a book about my identity as a Bengalurean, my acceptance of the city and my gratitude to it for accepting me. It is more of a thank-you note, than a love letter.”

Leave A Comment