July 11, 2003 | home

Matters of Taste

Issue of 2003-07-14 and 21

Posted 2003-07-07

“It’s hard to understand how something that tastes sweet in one person’s mouth, in another person’s mouth can taste so bitter,” a friend tells Abe Opincar, whose memoir, Fried Butter (Soho), explores the ways in which memory dictates gustatory preference. For others, it’s a matter of social class. In Rosemary and Bitter Oranges (Scribner), Patrizia Chen’s grandfather banned onions and garlic for their rusticity; years later, Chen served him a dish laced with the forbidden seasonings. He praised her culinary genius. “But Nonno never found out about my Machiavellian deviousness,” she writes. “I loved him too much to show him, at the end of his life, how his inflexibility had deprived him of one of life’s great pleasures.”

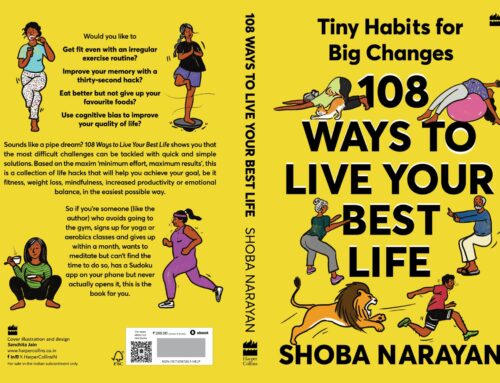

In South India, as Shoba Narayan relates in her memoir Monsoon Diary (Villard), food is enriched by ritual importance, from the choru-unnal (the first meal of an infant) to the elaborate feast that commemorates a marriage. When she left Madras to attend school in the United States, Narayan craved bowls of yogurt and rice to ease her homesickness: “While the foreign flavors teased my palate, I needed Indian food to ground me.”

Rather than seeking refuge in food from home, Victoria Abbott Riccardi, a New Yorker, learned to refine her taste buds during a year in Kyoto. In Untangling My Chopsticks (Broadway), Riccardi recalls her exploration of chakaiseki, a ceremonial meal of simple, seasonal courses that reflect the ritual’s monastic origins. “Like a junkie, I initially craved my stimulants,” she writes. “But then, ever so slowly, I started tasting—really tasting—the ingredients. It was like entering a dark room on a sunny day.”

— Andrea Thompson

Leave A Comment