Like most journalists, I get lots of requests for meetings from people who have ideas to parlay, products to push, locations to publicize, and so on. Like most journalists, I am also prickly about such meetings because I don’t want to be played, as it were. The assumption is: hey, I know you have an agenda, but I’ll be damned if I am going to be your tool in pushing this agenda.

So you go in defensive and doubt everything. So it was with the IFA.

Before I went in, I said, let me write a column about funding for the arts because so many institutions are facing that. It turned out to be a piece about the IFA. Here it is below.

Why we don’t value our arts enough

No arts institution in India pays enough attention to cultivating demand

Shoba Narayan

First Published: Sat, Aug 17 2013. 12 06 AM IST

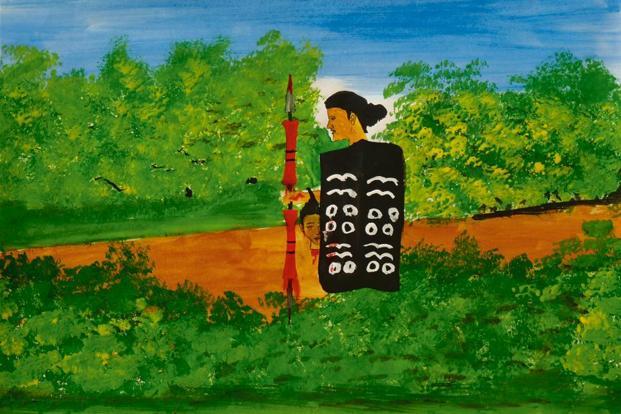

Animation film-maker Aditi Chitre explores visual arts of Nagaland. Photo courtesy: IFA

Arundhati Ghosh, the slim executive director of the India Foundation for the Arts (IFA), is telling me about fund-raising, specifically how hard it is to raise funds for the IFA. We are sitting at the French Loaf Bakery in Bangalore’s Richards Town, a lovely neighbourhood with a flavour of the quiet genteel city that this once used to be.

Ghosh says that there are about 400 “Friends of the IFA”, which is arguably India’s only grant-based arts-funding organization. I checked with my art sources in Mumbai and Delhi to verify this claim. There are residencies such as Khoj in Delhi and 1Shanthi Road in Bangalore; art and performance venues like Mumbai’s National Centre for Performing Arts (NCPA) and Prithvi Theatre; prizes to fund the arts such as the ŠKODA PRIZE, which was discontinued recently; arts foundations like Delhi’s Devi Art Foundation and Bangalore’s Tasveer Foundation that sponsor shows and talks. There are private museums like the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art and countless galleries that provide an ecosystem for the arts.

There is corporate support for the arts in ways large and small. The Himalaya Drug Company often sponsors theatre performances at Bangalore’s Ranga Shankara, itself an arts incubator and ecosystem. Sangita Jindal of Jindal Steel Works owns and runs the excellent ART India magazine and does heritage preservation in Hampi. The Mahindra Excellence in Theatre Awards (META) gets more press than the quieter and equally interesting Sanatkada Lucknow Festival that the company organizes. The Tatas have established institutions like the NCPA, but many of their trusts now focus on livelihoods. The Ratan Tata trust, for example, gives only 1% of its funds to ”culture”, according to their website. I couldn’t come up with a single organization that does what the IFA does.

I didn’t plan to write a column about the IFA. I have no connection with the organization and knew little about it till recently. What it does, and has done for the last 10 years, is give grants, ranging from Rs.3-8lakh, to arts projects of dizzying diversity. Gautam Pemmaraju of Mumbai used his Rs.5 lakh to explore the satirical poetic tradition in Dakhani known as the Mazahiya Shairi. Sajitha Madathil used Rs.3 lakh to study women’s participation in three different Kerala performance traditions: Kathakali, Mudiyattam, and Singari Melam. Navtej Johar of Delhi used his Rs.3 lakh to create a dance-drama based on Jean Genet’s play, The Maids. Tejal Shah used her grant to create a video installation that will feature at Documenta, a prestigious arts festival in Germany. Vidyun Sabhaney used his Rs.5 lakh grant to see how patachitra of Bengal, kaavad of Rajasthan and togalu gombeyatta of Karnataka depict stories from the Mahabharat. Kolkata Sanved of Kolkata used its Rs.8 lakh grant to run creative arts workshops with children living on railway stations. Aditi Chitre is exploring the visual arts of Nagaland. And so it goes. This model is problematic because individual companies don’t get brand recognition or PR from contributing to the IFA, although senior executives in various companies underwrite specific projects with a pan-Indian or regional bent. Tara Sinha, a former trustee, for example, funded a conference on Tamil movies, while Sandeep Singhal of investment firm WestBridge Capital underwrote a performance by the Mir musicians of Rajasthan.

By all accounts, the IFA is a worthy organization. Then, why are they having so much trouble raising funds? “The value of the arts is so intrinsic to our lives that it is almost invisible to us,” says Ghosh. “Other developmental needs like roti, kapda, makaan in India becomes more vital to support.” This is true. In the hierarchy of needs that weigh down our society, education, water, poverty, sanitation, livelihood and a whole host of health concerns rise up to the surface. Funding the arts pales in comparison with the exigencies of cancer research or educating the girl child. Simply put, we don’t know how to value art in our society. “Everyone has an idea on what’s art and what is ‘good’ art,” says Ghosh. “If you fund a school, such debates are limited, but not so in the arts.” The income tax exemption of 50% doesn’t help either. Gifts in kind such as land, building or paintings don’t get any exemptions. No wonder more NCPAs aren’t built—nobody wants to donate the land.

I called Lalit Bhasin, a Supreme Court lawyer, and a trustee of the IFA, to find out why he supports the arts. “Every other activity has a support system—not the arts,” he says. “As a lawyer, I can say that we have set up libraries for budding young lawyers. We help with education, medicine and the environment. The arts have been left behind with no one to project or promote it.”

Jaithirth Rao, another IFA trustee, makes a different kind of argument. By focusing on economics and security, he says, we will imitate the Prussian model, and “we know what happened to that model in 1945”. He links the arts to livelihood—I can see the long arm of fund-raising in this. “Our work on Rajasthani folk music, virtually a new genre which seems to be commercially viable has emerged. The work on Tamil Nadu murals could boost tourism. For the next level of economic growth, we cannot be order takers—we need our own creativity. Remember, (Steve) Jobs studied calligraphy in college,” says Rao.

There is another more complex reason why the IFA and other arts institutions are having trouble with raising funds, and it demands another column. Here is a hint: No arts institution in India pays enough attention to cultivating demand. They assume that funding worthwhile projects is enough. It isn’t.

Shoba Narayan is researching demand for the arts for her next column.

Leave A Comment