Normally, publications excerpt the first pages of the book. That is when the writing is brisk, and draws the readers. Or at least, that’s the assumption.

Lit Hub, which I love (along with Maria Popova’s Brain Pickings), went against the grain. They excerpted a different section pasted below– lovely photo of a Desi cow and linked here

MILK, MOTHERHOOD, AND THE LAST REFUGE OF THE SACRED COW

SHOBA NARAYAN EXPLORES THE MYTHS OF MILK AND THE BACKSTREETS OF BANGALORE

Why is milk considered sacred in several cultures, not just in Indian culture? Is it because we begin our lives with milk? The Greek goddess Hera spilled her breast milk and created not a wardrobe malfunction, but the Milky Way. When her husband Zeus lusted after a beautiful maiden called Europa, a jealous Hera turned Europa into a white cow and drove her into the continent that bears that name and made the term cow into an epithet to be forever used by jealous women and angry men. Not a woman to be trifled with, our Hera.

The Old Testament mentions the “land that floweth with milk and honey” over a dozen times, always in a positive way. Judaism prohibits milk and meat to be mixed or eaten together. The Koran contains a passage about the origin and importance of milk: “And surely in the livestock there is a lesson for you. . . ” The Ramadan fast is traditionally broken with dates and a glass of milk.

Milk is part of cultural slang (“to milk someone”).

“The milk of human kindness,” wrote Shakespeare in Macbeth.

“As pure as milk,” goes the expression.

Well, perhaps not so pure anymore. Milk has become a minefield with respect to nutrition. Current medical literature blames milk for everything from iron deficiency and colic to Type One diabetes and some kinds of cancers. Vegans believe that milk poisons the body. Most ancient cultures believed the opposite. They got their protein from milk and its byproducts. The Turkish salty sheep’s-milk cheese beyaz peynir and the Indian cheese paneer both hark back 7,000 years to when Neolithic populations attempted to tap the high nutritional punch of milk by converting it into easily digested cheese. Indian literature views milk as a benign super food. Ayurveda touts milk products as calming and healing. Elders sometimes fast by consuming nothing but milk or they break a strict fast with a glass of milk.

Priests perform rituals on a stomach empty of all nourishment except for milk, which is okay to drink. It is above ritual, above rules, and all about faith. Ritual offerings of milk and yogurt are customary in Hindu temples.

Religion is filled with animals of all sorts, not just cows. White horses, such as Pegasus, feature prominently in Greek, Celtic, Slavic, and Indian mythology. Birds abound: as messengers, soothsayers, and predictors of good or bad events. But cows are imbued with particular qualities in Indian mythology. They nurture and save humans. They exude a certain patience, an acceptance. Some have said a “maternal acceptance.” But I know that motherly acceptance is mostly an oxymoron. Mothers can be cheerleaders and champions but they also push and nag in ways that are the opposite of acceptance. Mothers are annoying—I say this as both a mother and a daughter—and not necessarily accepting.

“Cows nurture and save humans. They exude a certain patience, an acceptance.”

Sarala is a tranquil and calm mother. I can tell. Her sons circle around her like moons. Their chronic lack of money hasn’t cleaved the family apart. Quite the opposite, in fact. A dozen people live in Sarala’s one-room tenement: she and her husband, Naidu; their first son, Senthil, and his wife; their remaining three sons (one of whom is not her biological son but was born to her cousin; Sarala has raised him); and her brother’s family of four.

Sharing information and assistance is part of who Sarala is. The army wives constantly ask her for advice on healing through herbs—naatu vaidhyam, it is called, or “country medicine.”

One day, she brings an egg curry that she has made for a pregnant army mother. “It will give you warmth during this cold winter,” she says.

When I complain of a backache, she shows up at my doorstep with what appears to be white, wobbly custard. “One of my cows just gave birth. This is the first milk of the cow. It will give your back strength,” she says.

Turns out that the sweet milky substance that Sarala has given me is colostrum, the first milk that a cow feeds its calf. It is filled with nutrients and antibodies.

Sarala assures me that she isn’t depriving the calf. “We only take a small amount of leftover, after the calf has drunk its fill,” she says.

I take the stainless-steel container hesitantly, not wanting to offend her. Sarala has told me that it is sweet and that I should just swallow it like custard. I don’t feel like eating a cow’s colostrum.

When our cook, Geeta, sees the dish, she gasps. “Do you know how hard it is to get this?” she asks. “Dairy farmers in the village charge a lot for this dish. It is like gold. To think that she gave it to you for free!” There is respect in Geeta’s eyes for my milk woman.

The colostrum signifies a change in our relationship. There is a lot more give and take. When I casually mention that I have guests for dinner, Sarala throws in an extra liter of milk, no charge.

*

Cows are the epitome of patience in the Indian community network. Goats are tetchy, arching their necks stubbornly against the rope as they get pulled down the streets. Roosters scratch the ground moodily. Stray dogs are hyper—racing each other, chasing their tail; cats, aloof; and crows, clingy. Cows wait their turn. Their eyes look at eternity. As animal species go, cows have a good temperament. Not all of them—the Tapti Khillar cows that can outrun a horse across ravines and rock formations are like moody, bad-tempered divas—but most cows are pretty even tempered. They have to be in order to adjust to the urban environment. Cows aren’t fazed by traffic. They amble right through or simply stand or sit.

One of Sarala’s best milkers often falls asleep right beside the road divider. I ask Sarala if she is worried about her cow getting hit by traffic. She shakes her head. Who will hit a cow in India, she asks?

“I have observed cows ambling across highways, sleeping at night on roads, and lying beside the median on busy streets. These animals are nuts, I think. Or worse, dumb. They are inviting death. But it doesn’t seem to happen.”

One day, I watch a cow standing in the middle of the road. Vehicles race by: dozens of rickshaws, trucks spewing diesel, buses overflowing with people, cars of every stripe, bicycles with school children riding side saddle, standard issue bullock carts, scooters with two riders and a goat straddled between—the usual cross section of traffic in India. They all come hurtling down and screech to a halt before swerving crazily around the cow while somehow managing to avoid each other. Not once does the cow get hit; nobody comes even close.

Since then, I have observed cows ambling across highways, sleeping at night on roads, and lying beside the median on busy streets. These animals are nuts, I think. Or worse, dumb. They are inviting death. But it doesn’t seem to happen. It is the traffic that swerves to avoid the cow.

“Why is the cow so secure on Indian roads?” I ask Sarala.

“She is like your mother. Who will run over their mother?” she says.

When I don’t look convinced, she adds, “She is the giver of wealth, of prosperity. Why would you kill the goose that is laying golden eggs?”

I nod, surprised that Sarala knows that story. She takes my silence as disapproval.

“You have to shoo them away, Madam. Why don’t you do that?” Sarala accuses, taking the offensive. “When I see cows by the divider, I pick up a stick and shoo them over to the side. These animals don’t know any better. They don’t have as much brains as us.”

“I thought you said that they are as smart as humans,” I mutter, but I think of Sarala’s instructions every time I see a calf or cow sitting in the center of the road. The only problem is that it is hard to stop my car, get out, find a stick and shoo the animal away. There are too many vehicles honking behind me, their size inversely proportional to the volume of the horn. Mopeds trumpet like elephants; motorbikes roar like lions; my massive SUV that can fit ten people has a wheezy horn like a geezer’s cough. They all drive like maniacs but never seem to hit the animal. Is that fear of being cursed by Mother Cow, compassion for the mute bovine, or an ancient instinct that teaches humans to value livestock?

As my father, an English professor, notes, the word “cattle” comes from the Latin capitale, a term that referred to moveable personal assets. Walking bovines were moveable assets not just for hunter-gatherers but also for Sarala’s ancestors and mine. Not to mention Sarala herself.

Early humans domesticated cattle in two places. The Bos taurus species was domesticated 9,000 years ago in the Fertile Crescent, the strip of land that runs from the Nile River Valley through the Middle East to the Persian Gulf. The Bos indicus species was domesticated in the Indus Valley region in Baluchistan (in modern-day Pakistan) between 6500 and 5000 BC. Until then, wild aurochs about the size of Indian lorries (midsize moving trucks in America) had roamed the world and been immortalized 17,000 years ago in the cave paintings of Lascaux.

Domestication may have emerged as a solution to overhunting. Dorian Fuller, professor of archaeobotany at University College, London, writes, “Each step along the trajectory, from wild prey to game management, to herd management, to directed breeding, may not have been guided by a desire to completely control the animals’ life history but instead to increase the supply of a vanishing resource. In this way, animal domestication mirrors the process of unintentional entanglement associated with plant domestication as humans first foraged and then, through increased reliance on the resource, became trapped in positive feedback cycles of increasing labor and management of plant species that were evolving in response to human innovations.” Humans and cattle came together, with each dependent on the other. Sometimes, after killing animals, humans took in their young and nurtured them as pets. Large males were hunted because they had a higher amount of animal protein, leaving the smaller males to mate with the females, thus selectively and perhaps inadvertently breeding smaller-sized cattle over several generations. Docility and adaptation were prized and selectively bred, leading to the taming of the shrewish aurochs into the docile cows that we see today. The wild auroch went extinct when the last one died in Poland in 1627. Now there are attempts to resuscitate them through genetics.

The Bos indicus, known as zebu or hump-backed cattle, is characterized by a fatty hump above the shoulders, folded dewlaps, droopy ears, and more sweat glands than their European cousins. In India, they are simply called desi or “native cows.” These cows can handle hot, humid climes. The Indian food chain, even in busy urban cities, still links cows and humans. In my home, for instance, I boil cow’s milk every morning, then let the milk cool a little before scooping out the cream on top and setting the remainder into yogurt. I collect the cream for a week and then churn it to separate the butter from the buttermilk. I divide the butter into two parts: one for sweet cream butter to spread on my children’s toast and the other to boil into ghee or clarified butter. The whole thing is a painstaking process—a nuisance, really—but I do it. As do many of my neighbors. We set yogurt, churn butter and when needed, squeeze a bit of lemon juice into the milk to curdle it into fresh paneer. Doing all this is a daily reminder of all we get from a cow, the giver of good things.

__________________________________

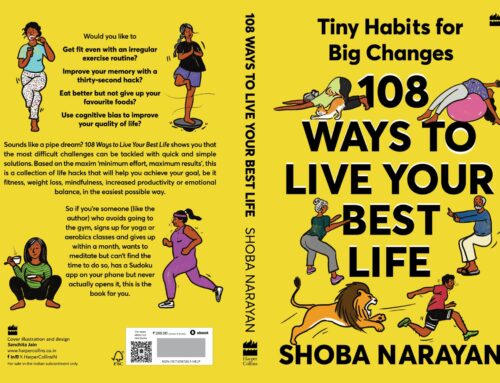

From The Milk Lady of Bangalore: An Unexpected Adventure. Used with permission of Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill. Copyright © 2018 by Shoba Narayan.

Leave A Comment