How Indian craft chocolate makers are upping their game by mixing indigenous

ingredients with locally grown cacao.

An hour outside Vijayawada, in the South Indian state of Andhra Pradesh, lies the delta of the Godavari River. Small towns with musical names — Eluru, Jalipudi, Ganguru — dot this fertile landscape, ringed by farmland so intensely green they say it cools the eyes. There are lush paddies and sugarcane fields, thick stands of banana and coconut trees. And flourishing alongside them is a newer crop: cacao. “After eating our chocolate, you will never touch a Lindt or Godiva again,” says

Chaitanya Muppala with the bravado of a startup founder, which he is. Tall and loose-limbed, the thirty-something Hyderabad-based entrepreneur is the man behind Manam Chocolate, a new craft-chocolate brand that aims to overturn the poor reputation of Indian cacao. On this warm March morning, he’s sitting under a ficus tree chatting with his cacao farmers over milky ginger chai. He inquires after their families, they talk shop about crops, he tells a young second-generation farmer to ride shotgun with him and learn about the world of fine-flavor cacao.

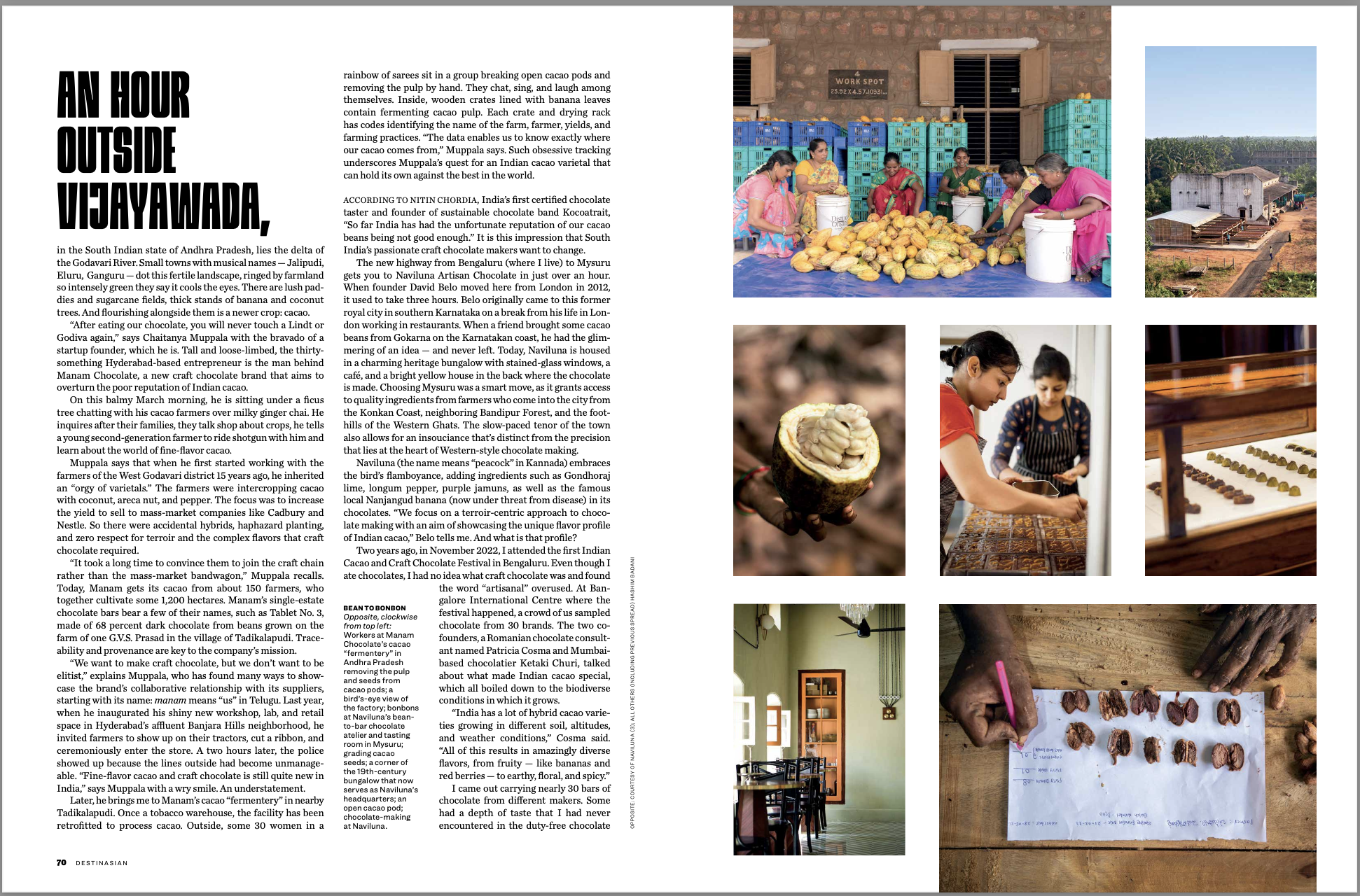

Muppala says that when he first started working with the farmers of the West Godavari district 15 years ago, he inherited an “orgy of varietals.” The farmers were intercropping cacao with coconut, areca nut, and pepper. The focus was to increase the yield to sell to mass-market companies like Cadbury and Nestle. So there were accidental hybrids, haphazard planting, and zero respect for terroir and the complex flavors that craft chocolate required. “It took a long time to convince them to join the craft chain rather than the mass-market bandwagon,” Muppala recalls. Today, Manam gets it cacao from about 150 farmers, who together cultivate some 1,200 hectares. Manam’s single-estate chocolate bars bear a few of their names, such as Tablet No. 3, made of 68 percent dark chocolate from beans grown on the farm of one G.V.S. Prasad in the village of Tadikalapudi. Traceability and provenance are key to the company’s mission. “We want to make craft chocolate, but we don’t want to be elitist,” explains Muppala, who has found many ways to showcase the brand’s collaborative relationship with its farmers, starting with its name: manam means “us” in Telegu. Last year, when he inaugurated his shiny new workshop, lab, and retail space in Hyderabad’s Banjara Hills neighborhood, he invited farmers to show up on their tractors, cut a ribbon, and ceremoniously entered the store. A couple of hours later, the police showed up because the lines outside had become unmanageable. “Fine flavor cacao and craft chocolate is still new in India,” says Muppala with a wry smile. An understatement.

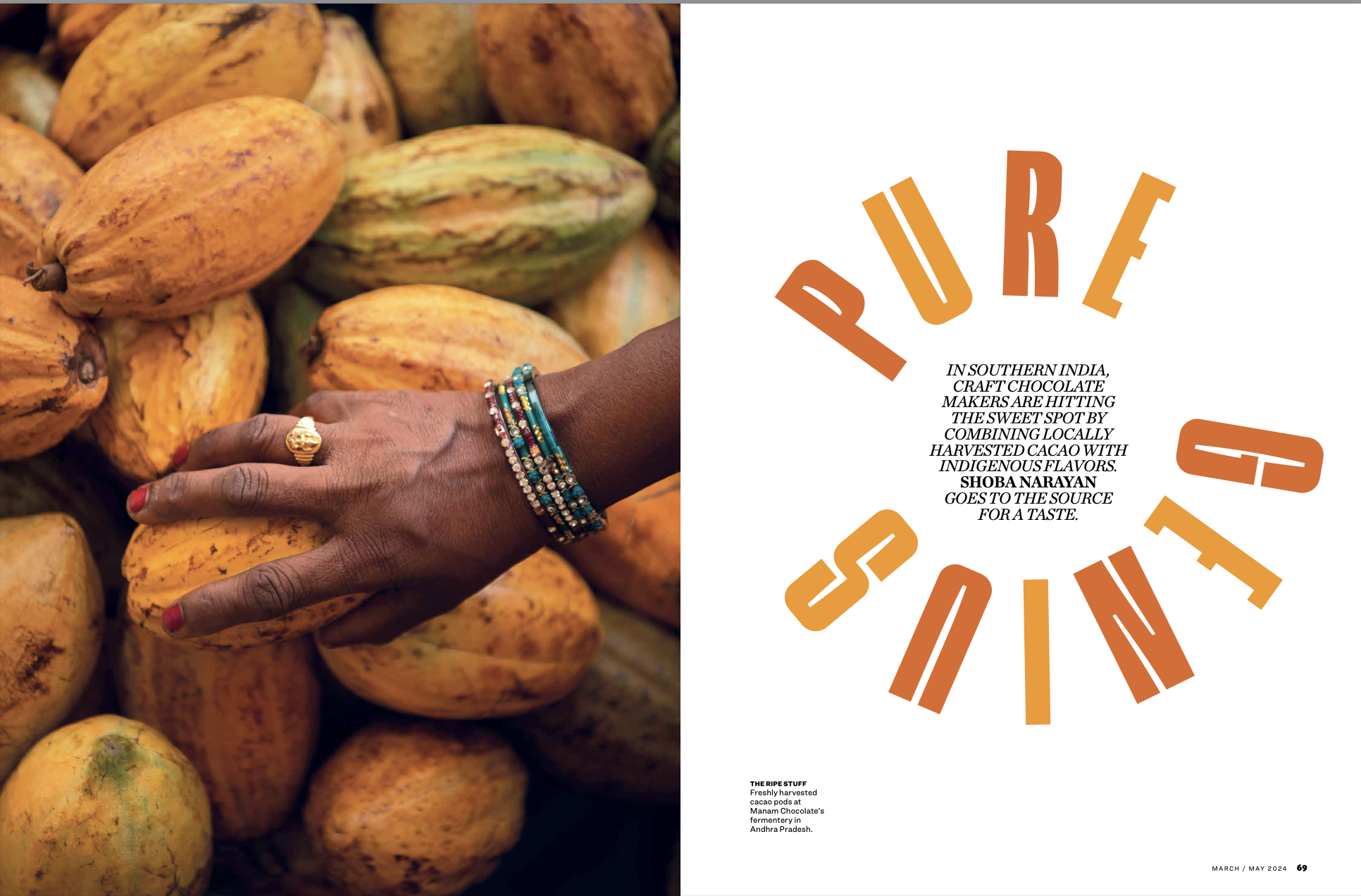

Later, he brings me to his cacao “fermentary” in nearby Tadikalapudi. Once a tobacco warehouse, the facility has been retrofitted to process cacao. Outside, some 30 women in a rainbow of sarees sit in a group breaking open cacao pods and removing the pulp by hand. They chat, sing, and laugh among themselves. Inside, wooden crates lined with banana leaves contain fermenting cacao pulp. Each crate and drying rack has codes identifying the name of the farm, farmer, yields, and farming practices. “The data enables us to know we know exactly who our cacao comes from,” Muppala says. Such obsessive tracking underscore Muppala’s quest for a golden Indian cacao varietal that can hold its own against the best cacaos of the world.

***

According to Nitin Chordia, India’s first certified chocolate taster and founder of the Kocoatrait Sustainable Chocolates, “So far India has had the unfortunate reputation of our cacao beans being not good enough.” It is this impression that South India’s passionate craft-chocolate makers want to change.

The new highway from Bengaluru (where I live) to Mysuru gets you to Naviluna Artisan Chocolate in just over an hour. When founder David Belo moved here from London in 2012, it used to take three hours. Belo originally came to this former royal city in southern Karnataka on a break from his life in London working in restaurants. When a friend brought some cacao beans from Gokarna on the Karnatakan coast, he had the glimmering of an idea — and never left. Today, Naviluna is housed in a charming heritage bungalow with stained-glass windows, a café, and a bright yellow house in the back where the chocolate is made. Choosing Mysuru was a smart move. On the other side are the forests of Western Ghats where tigers roam and monkeys call. At the edges of the forests are the farms were cacao is intercropped. Mysuru is the cultural heart of Karnataka state, known for its Kannada literature and distinctive cuisine.

Naviluna (the name means “peacock” in Kannada) embraces the bird’s flamboyance, adding ingredients such as Gondhoraj lime, longum pepper, purple jamuns, as well as the famous local Nanjangud banana (now under threat from disease) in its chocolates. “We focus on a terror-centric approach to chocolate making with an aim of showcasing the unique flavor profile of Indian cacao,” Belo tells me. And what is that profile?

Two years ago, in November 2022, I attended the first Indian Cacao and Craft Chocolate Festival in Bengaluru. Even though I ate chocolates, I had no idea what craft chocolate was and found the word “artisanal” overused. At Bangalore International Centre where the festival happened, a crowd of us sampled chocolate from 30 brands. The two co-founders, a Romanian chocolate consultant named Patricia Cosma and Mumbai-based chocolatier Ketaki Churi, talked about what made Indian cacao special, which all boiled down to the biodiverse conditions in which it grew. “India has a lot of hybrid cacao varieties growing in different soil, altitude, weather conditions,” Cosma said. “All this results in amazingly diverse flavors, from fruity — like red berries and bananas — to earthy, floral, spice.”

I came out carrying nearly 30 bars of chocolate from different makers. Some had a depth of taste that I had never encountered in the duty-free chocolate that I usually buy. Some had familiar hints of cardamom or chili. Some tasted weird and funky. Some single-origin dark chocolate was too intense. As Muppala told me, “We all grew up eating Dairy Milk, so our palates have to adjust.”

The festival has continued across different locations in India and will return to Bengaluru this November. Of the lot I tasted, a handful of brands are taking the craft to the next level. Manam and Naviluna, of course, but also Soklet, Paul & Mike, Bon Fiction, Mason & Co, and Kocoatrait. It is a tight-knit universe where everyone knows each other. All these brands follow largely the same formula. They source local cacao beans, use a idli grinder, very common in Indian kitchens, to grind the beans before conching it and pouring into molds for slabs of chocolate. The couverture is used to make truffles, bonbons and the like. This is where they get to play. Petite and smiling, Chef Ruby Islam bend over chocolate truffles at the Manam show kitchen in Hyderabad imbueing it with ingredients like curry leaves and coconut, mint and matcha. “Chocolate is a forgiving ingredient, so you can take more risks than in a traditional pastry recipe,” she says. On weekends, she shows school children how to make chocolate, her kitchen reverberating with their giggles and laughs.

***

The best part of visiting Mason & Co chocolate in the onetime French colony of Pondicherry is to see the smiling faces of the people who run the place — and they are all women. This too is a happy result in craft chocolate. In India, where female participation in the workforce is abysmal, craft chocolate allows for women to participate at every stage, from farming to sorting to creating. Nearly 20 ladies run every aspect of the chocolate making at Mason & Co. “Our lives have been transformed,” one tells me on my most recent visit.

The same happens at Soklet, a well-respected brand from the Anamalai Hills near Coimbatore, where I was born. “We were already growing cacao but didn’t want to be one among the thousand farmers who sell to mass-market chocolate brands,” says Harish Kumar, who founded the company with his brother-in-law. Produced from cacao harvested on the family’s plantation in Pollachi, Soklet retails in Europe and is one of the few Indian brands to feature on the London-based craft-chocolate platform Cocoa Runners. Here too women of the family are strongly involved in making and marketing chocolate, sharing an easy rapport with the farmers who have lived in the region for generations.

Even though each of South India’s craft chocolate brands use similar processes, they have their own stamp of individuality. Kocoatrait brands itself as sustainable; Mason & Co stresses its female workforce and vegan credentials; Naviluna focuses on terroir, and Soklet on its tree-to-bar chain; Manam wants to be the best. All of them have an uphill battle not just because craft chocolate is new in India but also because cacao prices have skyrocketed in the last several months. “It’s going to weed out a lot of brands that are not here to stay,” says Soklet’s Kumar.

Chocolate is both a food and an emotion. In India, all this gets amplified by the organized chaos of the landscape, the farmers, and the personal quirks of the makers. It may not create the best craft chocolate in the world, but it can aspire to be the most memorable, with strange and interesting ingredients that remind you of the home you left, the love you lost, or the idea whose time has come.

Leave A Comment