It is early March and the Louise M. Davies Symphony Hall in California, permanent home to the San Francisco Symphony, is packed with patrons who have gathered to listen to Russian composer Alexander Scriabin’s Prometheus: The Poem Of Fire. The performance has been billed as unique, nothing like the ones they have given since 1911. What has brought me and many other patrons here is the promise of scent. The House of Cartier has created three scents that will perfume the hall at three key points during the performance—but we are not certain how it will be achieved. The only clues are white vortex-shaped structures along the sides of the auditorium.

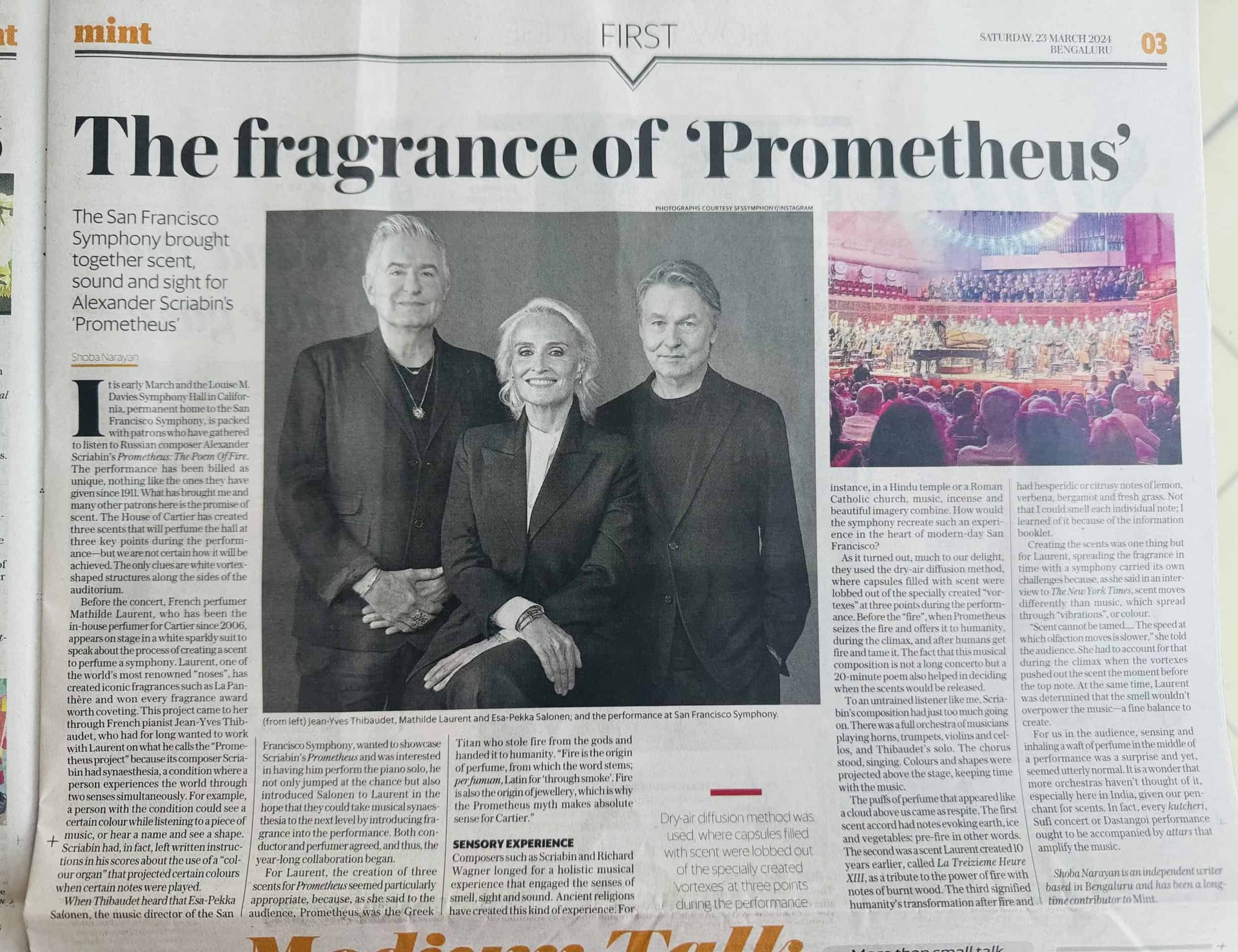

Before the concert, French perfumer Mathilde Laurent, who has been the in-house perfumer for Cartier since 2006, appears on stage in a white sparkly suit to speak about the process of creating a scent to perfume a symphony. Laurent, one of the world’s most renowned “noses”, has created iconic fragrances such as La Panthère and won every fragrance award worth coveting. This project came to her through French pianist Jean-Yves Thibaudet, who had for long wanted to work with Laurent on what he calls the “Prometheus project” because its composer Scriabin had synaesthesia, a condition where a person experiences the world through two senses simultaneously. For example, a person with the condition could see a certain colour while listening to a piece of music, or hear a name and see a shape. Scriabin had, in fact, left written instructions in his scores about the use of a “colour organ” that projected certain colours when certain notes were played.

When Thibaudet heard that Esa-Pekka Salonen, the music director of the San Francisco Symphony, wanted to showcase Scriabin’s Prometheus and was interested in having him perform the piano solo, he not only jumped at the chance but also introduced Salonen to Laurent in the hope that they could take musical synaesthesia to the next level by introducing fragrance into the performance. Both conductor and perfumer agreed, and thus, the year-long collaboration began.

For Laurent, the creation of three scents for Prometheus seemed particularly appropriate, because, as she said to the audience, Prometheus was the Greek Titan who stole fire from the gods and handed it to humanity. “Fire is the origin of perfume, from which the word stems; per fumum, Latin for “through smoke”. Fire is also the origin of jewellery, which is why the Prometheus myth makes absolute sense for Cartier.”

In India, the art of sculptures combines with devotional music and the scent of incense to create a beautiful imagery and experience. There are similarities to an experience in a Roman Catholic church where music meets the scent of candles and incense. Composers such as Scriabin and Richard Wagner also longed for such a holistic musical experience that engaged the senses of smell, sight and sound, as embodied by ancient religions. How would the symphony recreate such an experience in the heart of modern-day San Francisco?

As it turned out, much to our delight, they used the dry-air diffusion method, where capsules filled with scent were lobbed out of the specially created “vortexes” at three points during the performance. Before the “fire”, when Prometheus seizes the fire and offers it to humanity, during the climax, and after humans get fire and tame it. The fact that this musical composition is not a long concerto but a 20-minute poem also helped in deciding when the scents would be released.

To an untrained listener like me, Scriabin’s composition had just too much going on. There was a full orchestra of musicians playing horns, trumpets, violins and cellos, and Thibaudet’s solo. The chorus stood, singing. Colours and shapes were projected above the stage, keeping time with the music.

The puffs of perfume that appeared like a cloud above us came as respite. The first scent accord had notes evoking earth, ice and vegetables: pre-fire in other words. The second was a scent Laurent created 10 years earlier, called La Treizieme Heure XIII, as a tribute to the power of fire with notes of burnt wood. The third signified humanity’s transformation after fire and had hesperidic or citrusy notes of lemon, verbena, bergamot and fresh grass. Not that I could smell each individual note; I learned of it because of the information booklet.

Creating the scents was one thing but for Laurent, spreading the fragrance in time with a symphony carried its own challenges because, as she said in an interview to The New York Times, scent moves differently than music, which spread through “vibrations”, or colour.

“Scent cannot be tamed…. The speed at which olfaction moves is slower,” she told the audience. She had to account for that during the climax when the vortexes pushed out the scent the moment before the top note. At the same time, Laurent was determined that the smell wouldn’t overpower the music—a fine balance to create.

For us in the audience, sensing and inhaling a waft of perfume in the middle of a performance was a surprise and yet, seemed utterly normal. It is a wonder that more orchestras haven’t thought of it, especially here in India, given our penchant for scents. In fact, every kutcheri, Sufi concert or Dastangoi performance ought to be accompanied by attars that amplify the music.

Shoba Narayan is an independent writer based in Bengaluru and has been a long-time contributor to Mint.

Leave A Comment