FROM CONDENAST TRAVELER OCTOBER 2005 ISSUE

A river runs through them, yes, but that’s not all that connects the former French colonies of Cambodia and Laos.

Shoba Narayan plies Southeast Asia’s new tourist axis

Cambodia is like a lotus bud concealing an onion—serene on the surface but eliciting tears as you peel back the layers. The awesome scale and spectacle of the Angkor temples contrast sharply with the ghostly photos and skulls of civilians murdered by the Khmer Rouge in the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum. The endless peace of a Buddhist monastery gives way to the raucous din of cyclos and tuk–tuks. The magnificent sunsets over the Mekong do nothing to diminish the ugly pallor of poverty. It is a young country but an old civilization that reached its zenith in the twelfth century, when the Hindu god–kings (devarajas) built massive stone temples while embracing Buddhism, now the predominant religion.

I am in Cambodia to meet a monk and to travel the Mekong. Being Hindu, I believe in the power of a monk’s blessing, and Cambodian monks are way up there in the spiritual hierarchy. So I, like the betrayed people of this ravaged land, line up to get blessed before setting out on my quest.

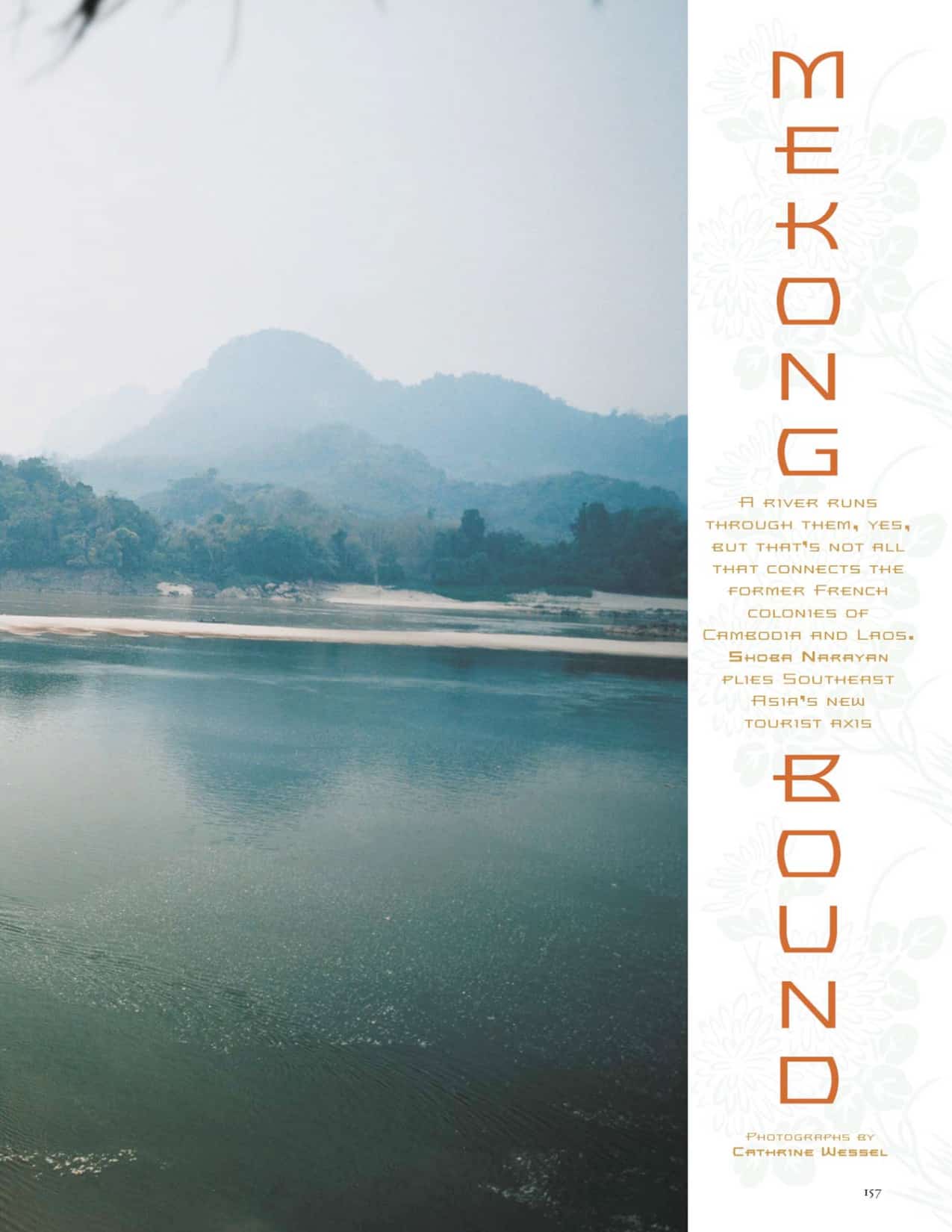

The Mekong is an obsession of mine. Other people track football scores. I track rivers. Rivers epitomize cultures; think of the Nile and Egypt, the Amazon and South America, the Ganges and India. Rivers are, to borrow a phrase, the cradles of civilization, carrying a country from its past into its future. In Asia, rivers are more than bodies of water. They are sources of celebration and symbols of fertility and prosperity. They are life itself.

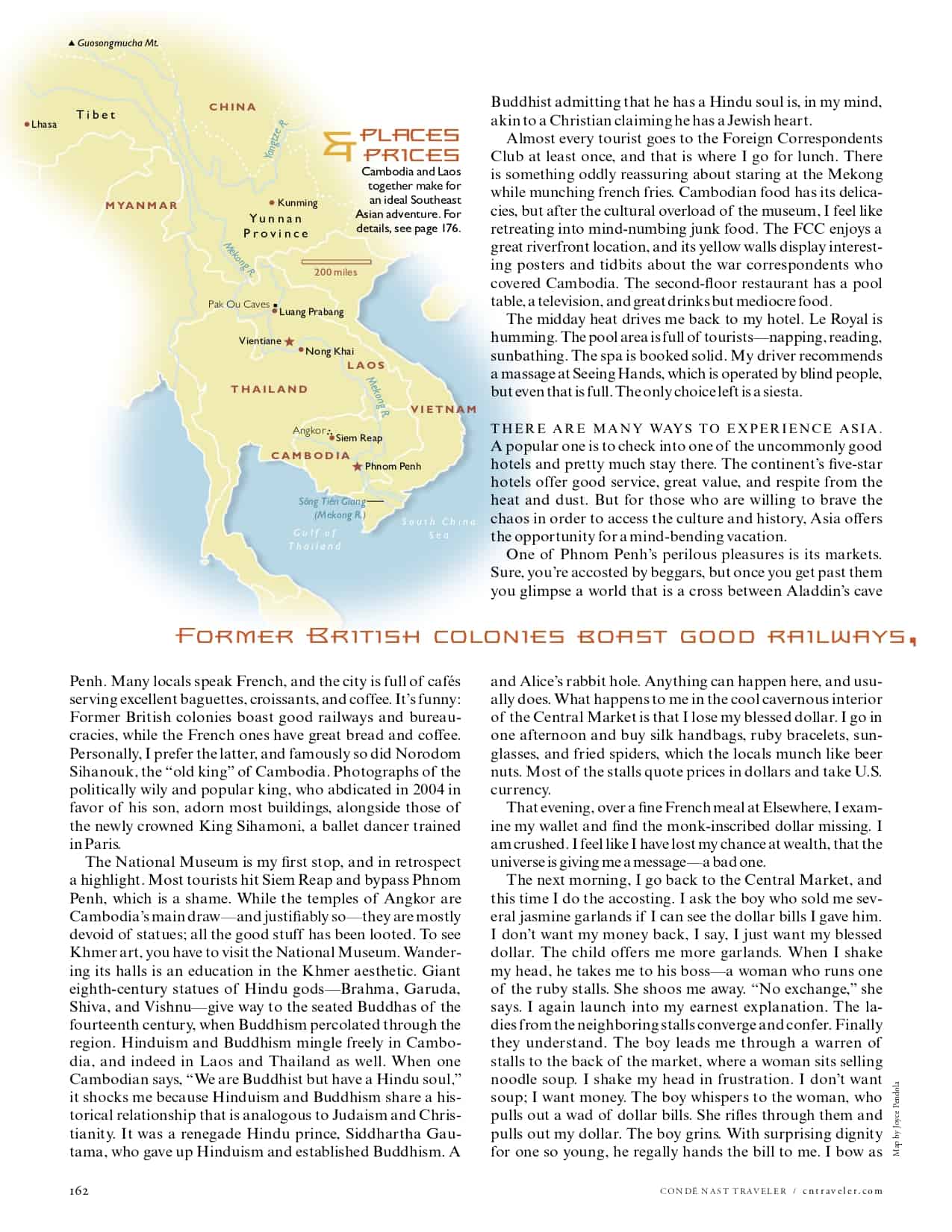

The Mekong is particularly interesting because it is intricately linked to the soul and psyche of six Asian countries (seven, if you consider Tibet to be independent but occupied). From its headwaters on China’s Guosongmucha Mountain, the Mekong descends sixteen thousand vertical feet through Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam before discharging into the South China Sea, some three thousand miles away.

I intend to follow the Mekong through the two countries that my time–constrained itinerary will allow. I rule out Thailand and Vietnam as too large, Myanmar and China’s Yunnan Province as too remote. That leaves Cambodia and Laos—two countries that naturally combine into one worthwhile trip.

My journey begins at dawn at Wat Saravantejo, in Phnom Penh. A monk is giving audience to a line of locals carrying babies, cell phones, and wads of Cambodian riels. The monk lights incense, sprinkles holy water on the babies, and blesses brand–new cell phones by chanting sonorous sutras. I wonder if he is being recorded, like a ring tone, but somehow doubt it. The monk’s blessing is to protect the phones, which are expensive and as important to Cambodians as BlackBerrys are to the perpetually plugged–in. He inscribes my U.S. dollar bill with Pali script, covering George Washington’s face in the process. Throw this money into the Mekong, he says through my translator, and it will come downriver to you multiplied tenfold. I tuck the bill carefully into my purse. Other monks may offer a passage to nirvana, but this one has given me a lottery ticket.

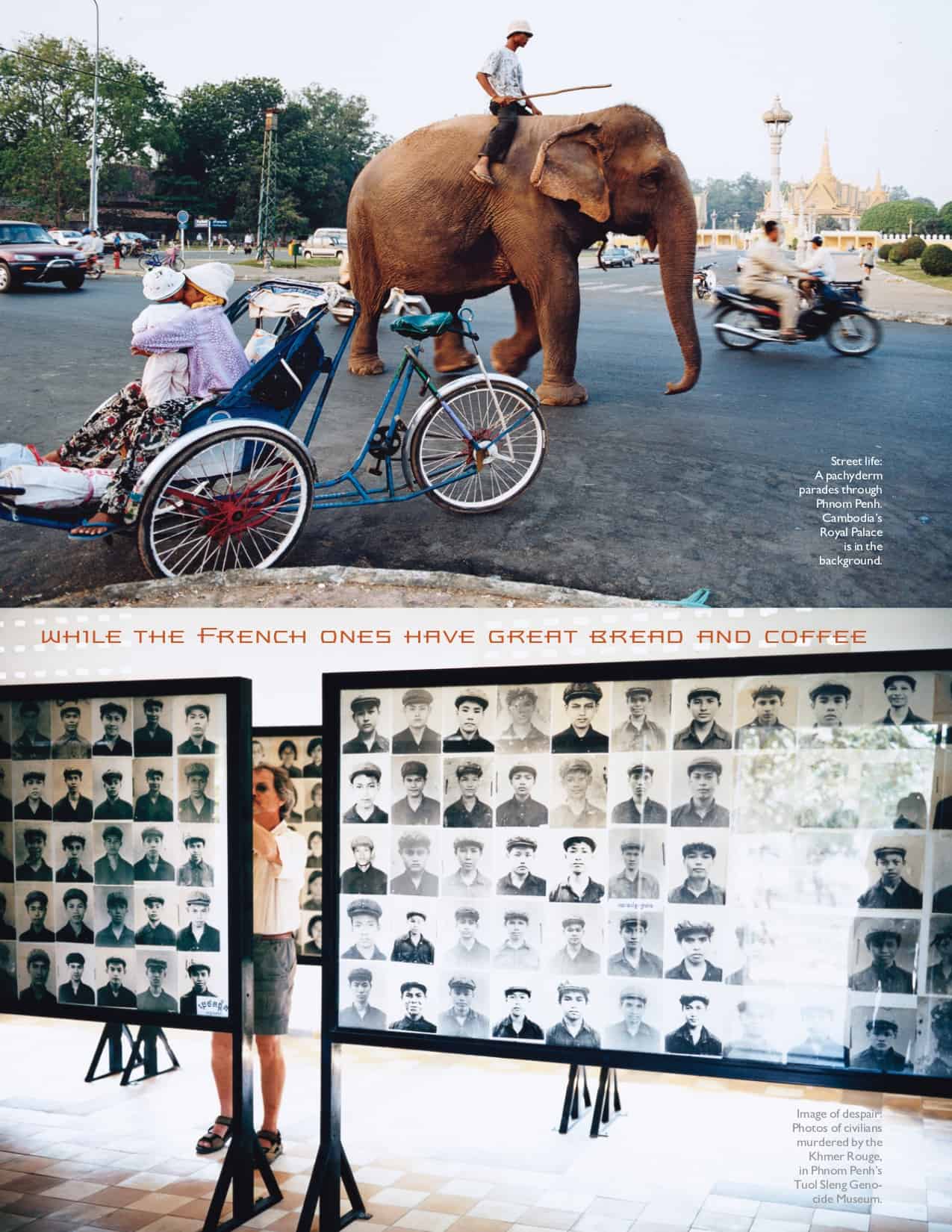

Outside, the morning sun casts a golden hue on the stirring city. As Asian capitals go, Phnom Penh, located at the confluence of the Bassac, Mekong, and Tonle Sap rivers, is one of the prettiest. Broad tree–lined boulevards bear a profusion of flowers—frangipani, gardenia, jasmine. The architecture is mostly French colonial interspersed with domed Buddhist stupas. A smattering of buildings by noted Khmer architect Van Molyvann reflect his geometric style. Molyvann designed the city’s Independence Monument to celebrate Cambodia’s freedom from French rule in 1953. France’s influence is still visible in Phnom Penh. Many locals speak French, and the city is full of cafés serving excellent baguettes, croissants, and coffee. It’s funny: Former British colonies boast good railways and bureaucracies, while the French ones have great bread and coffee. Personally, I prefer the latter, and famously so did Norodom Sihanouk, the “old king” of Cambodia. Photographs of the politically wily and popular king, who abdicated in 2004 in favor of his son, adorn most buildings, alongside those of the newly crowned King Sihamoni, a ballet dancer trained in Paris.

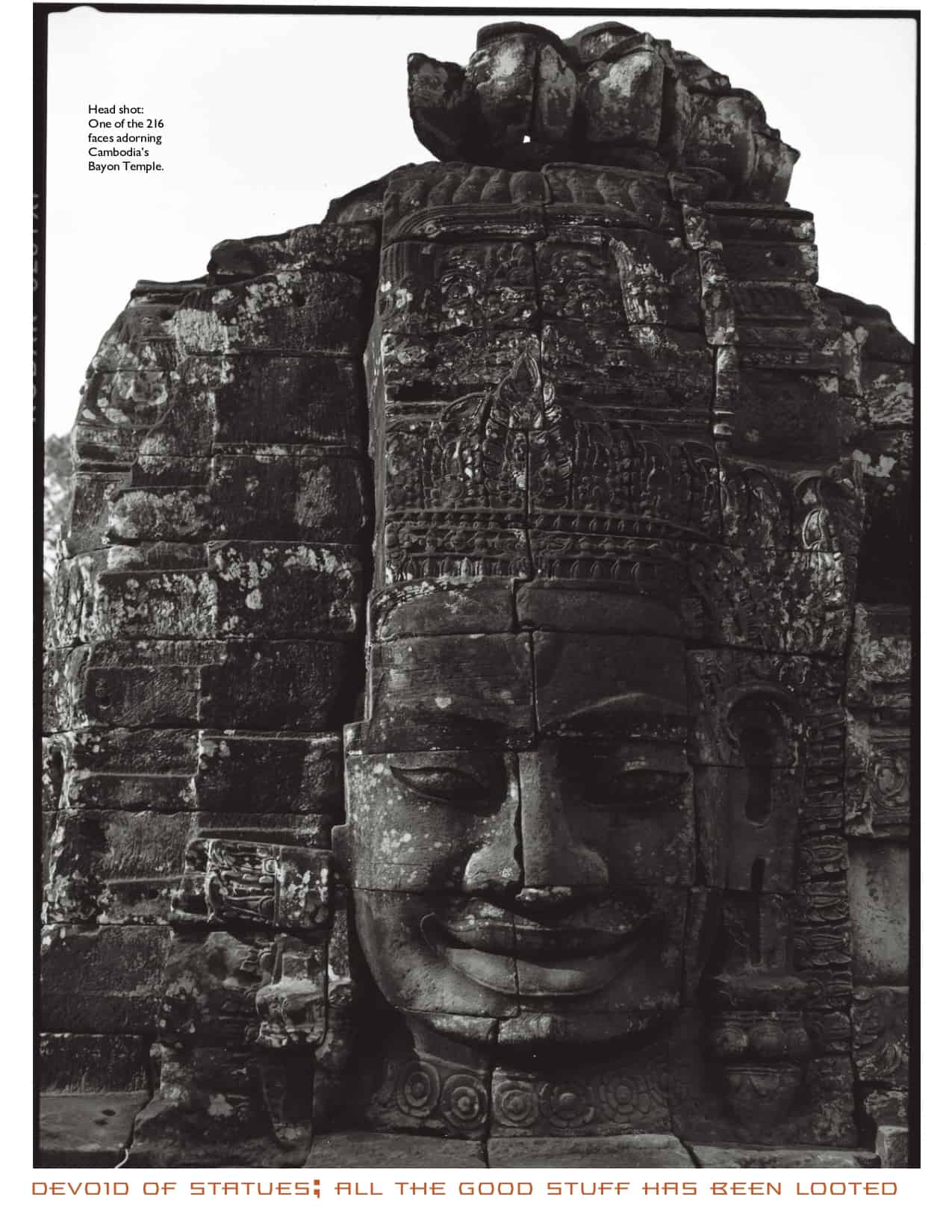

The National Museum is my first stop, and in retrospect a highlight. Most tourists hit Siem Reap and bypass Phnom Penh, which is a shame. While the temples of Angkor are Cambodia’s main draw—and justifiably so—they are mostly devoid of statues; all the good stuff has been looted. To see Khmer art, you have to visit the National Museum. Wandering its halls is an education in the Khmer aesthetic. Giant eighth–century statues of Hindu gods—Brahma, Garuda, Shiva, and Vishnu—give way to the seated Buddhas of the fourteenth century, when Buddhism percolated through the region. Hinduism and Buddhism mingle freely in Cambodia, and indeed in Laos and Thailand as well. When one Cambodian says, “We are Buddhist but have a Hindu soul,” it shocks me because Hinduism and Buddhism share a historical relationship that is analogous to Judaism and Christianity. It was a renegade Hindu prince, Siddhartha Gautama, who gave up Hinduism and established Buddhism. A Buddhist admitting that he has a Hindu soul is, in my mind, akin to a Christian claiming he has a Jewish heart.

Almost every tourist goes to the Foreign Correspondents Club at least once, and that is where I go for lunch. There is something oddly reassuring about staring at the Mekong while munching french fries. Cambodian food has its delicacies, but after the cultural overload of the museum, I feel like retreating into mind–numbing junk food. The FCC enjoys a great riverfront location, and its yellow walls display interesting posters and tidbits about the war correspondents who covered Cambodia. The second–floor restaurant has a pool table, a television, and great drinks but mediocre food.

The midday heat drives me back to my hotel. Le Royal is humming. The pool area is full of tourists—napping, reading, sunbathing. The spa is booked solid. My driver recommends a massage at Seeing Hands, which is operated by blind people, but even that is full. The only choice left is a siesta.

There are many ways to experience Asia. A popular one is to check into one of the uncommonly good hotels and pretty much stay there. The continent’s five–star hotels offer good service, great value, and respite from the heat and dust. But for those who are willing to brave the chaos in order to access the culture and history, Asia offers the opportunity for a mind–bending vacation.

One of Phnom Penh’s perilous pleasures is its markets. Sure, you’re accosted by beggars, but once you get past them you glimpse a world that is a cross between Aladdin’s cave and Alice’s rabbit hole. Anything can happen here, and usually does. What happens to me in the cool cavernous interior of the Central Market is that I lose my blessed dollar. I go in one afternoon and buy silk handbags, ruby bracelets, sunglasses, and fried spiders, which the locals munch like beer nuts. Most of the stalls quote prices in dollars and take U.S. currency.

That evening, over a fine French meal at Elsewhere, I examine my wallet and find the monk–inscribed dollar missing. I am crushed. I feel like I have lost my chance at wealth, that the universe is giving me a message—a bad one.

The next morning, I go back to the Central Market, and this time I do the accosting. I ask the boy who sold me several jasmine garlands if I can see the dollar bills I gave him. I don’t want my money back, I say, I just want my blessed dollar. The child offers me more garlands. When I shake my head, he takes me to his boss—a woman who runs one of the ruby stalls. She shoos me away. “No exchange,” she says. I again launch into my earnest explanation. The ladies from the neighboring stalls converge and confer. Finally they understand. The boy leads me through a warren of stalls to the back of the market, where a woman sits selling noodle soup. I shake my head in frustration. I don’t want soup; I want money. The boy whispers to the woman, who pulls out a wad of dollar bills. She rifles through them and pulls out my dollar. The boy grins. With surprising dignity for one so young, he regally hands the bill to me. I bow as I accept it, acknowledging the irony of the situation: I am receiving alms from the poor.

For those who have seen Bangkok’s Royal Palace and Emerald Buddha, Phnom Penh’s version of them will seem familiar. Curving naga heads rise gracefully from the red–tiled roof. Murals depicting the ubiquitous Ramayana—or the Reamker, as it is called in Khmer—enliven the throne room’s ceiling. The best part is the royal costume room, where for a small tip a woman will tie a jewel–toned silk sarong around your hips. When I visit, a group of German tourists are standing in line to be saronged and photographed.

In the neighboring Silver Pagoda, hundreds of Buddhas exhibiting a variety of mudras (hand gestures) are crammed into the dim room. The two–hundred–pound solid–gold Buddha and the “emerald” Buddha (made of green Baccarat crystal) are the highlights. The floor is sterling silver. As in all Buddhist temples, visitors are expected to cover their shoulders and legs.

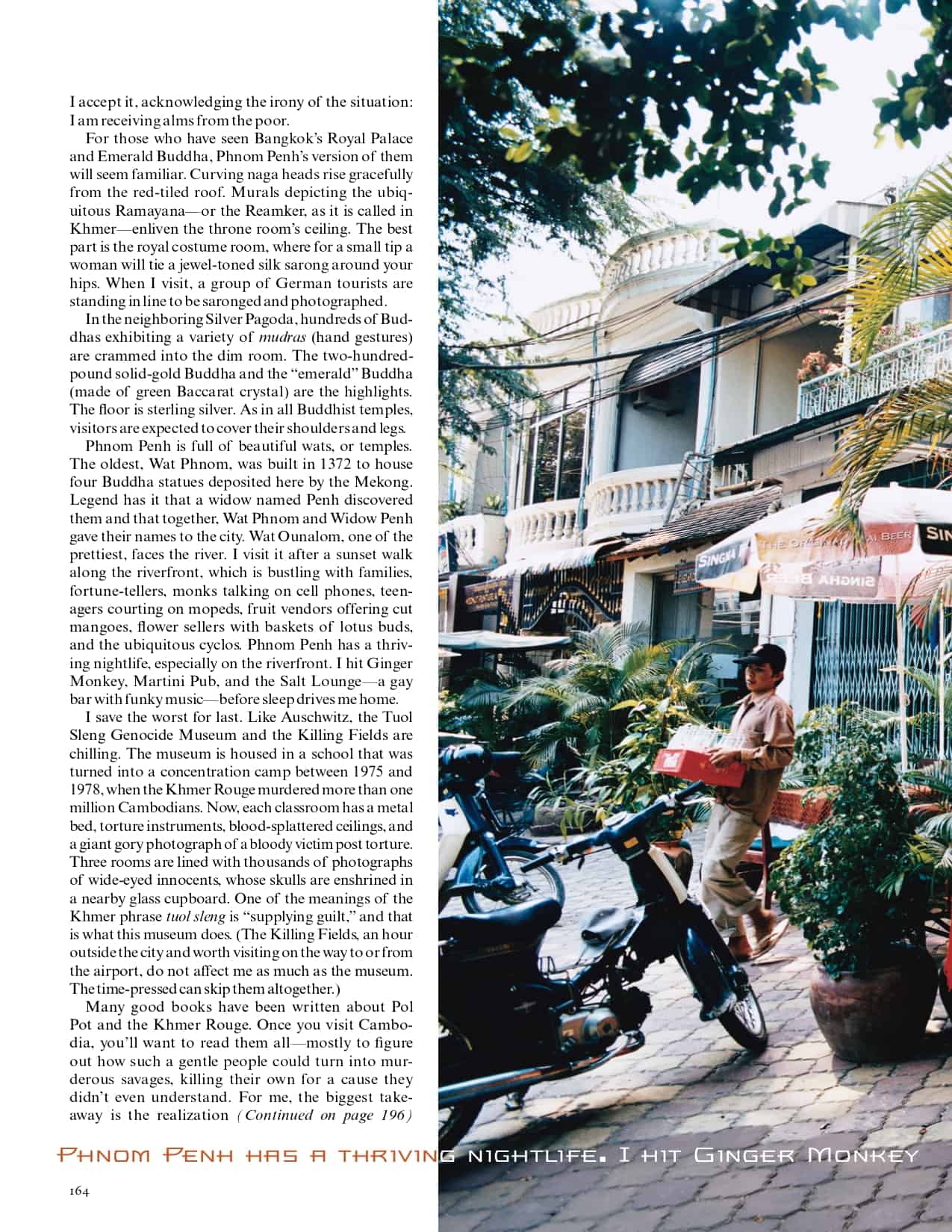

Phnom Penh is full of beautiful wats, or temples. The oldest, Wat Phnom, was built in 1372 to house four Buddha statues deposited here by the Mekong. Legend has it that a widow named Penh discovered them and that together, Wat Phnom and Widow Penh gave their names to the city. Wat Ounalom, one of the prettiest, faces the river. I visit it after a sunset walk along the riverfront, which is bustling with families, fortune–tellers, monks talking on cell phones, teenagers courting on mopeds, fruit vendors offering cut mangoes, flower sellers with baskets of lotus buds, and the ubiquitous cyclos. Phnom Penh has a thriving nightlife, especially on the riverfront. I hit Ginger Monkey, Martini Pub, and the Salt Lounge—a gay bar with funky music—before sleep drives me home.

I save the worst for last. Like Auschwitz, the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum and the Killing Fields are chilling. The museum is housed in a school that was turned into a concentration camp between 1975 and 1978, when the Khmer Rouge murdered more than one million Cambodians. Now, each classroom has a metal bed, torture instruments, blood–splattered ceilings, and a giant gory photograph of a bloody victim post torture. Three rooms are lined with thousands of photographs of wide–eyed innocents, whose skulls are enshrined in a nearby glass cupboard. One of the meanings of the Khmer phrase tuol sleng is “supplying guilt,” and that is what this museum does. (The Killing Fields, an hour outside the city and worth visiting on the way to or from the airport, do not affect me as much as the museum. The time–pressed can skip them altogether.)

Many good books have been written about Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge. Once you visit Cambodia, you’ll want to read them all—mostly to figure out how such a gentle people could turn into murderous savages, killing their own for a cause they didn’t even understand. For me, the biggest takeaway is the realization that this insane purge is not something I can dismiss as a fascist horror of my parents’ era. The Khmer Rouge was a nightmare of our time; it happened when I was a teenager.

Cambodians are still consumed by the tragedy. Ask anyone you see in Phnom Penh—cabdriver, monk, tour guide, waiter—about the Khmer Rouge and you will get a shockingly graphic account of mothers watching their children starve and die, of families going insane with grief as one member after another was murdered, all told in flat tones that discourage pity.

When I visit the Royal University of Fine Arts, a dispiriting campus that belies its name, I ask Preung Chhieng, the dean of choreographic arts, about the challenge of reviving traditional Apsara dance given that only thirty of Cambodia’s three hundred dancers survived the Khmer Rouge. Chhieng, a graceful man with high cheekbones and fine features, enjoyed the patronage of the royal family and was with them in Beijing during Pol Pot’s reign. After returning to Phnom Penh in 1978, he traveled through the provinces trying to round up all the remaining dancers. Together, they began a twenty–year effort to rejuvenate Khmer art forms. “The mission of preservation is ongoing,” Chhieng says, “but the arts are finally not endangered.”

Chhieng’s student Sophiline Cheam Shapiro, a dancer whose story was part of the anthology Children of Cambodia’s Killing Fields, is keeping the faith in her own way. She and her American husband founded the Khmer Arts Academy, in Long Beach, California, and she is on campus during my visit to train Khmer dancers for an upcoming American tour, taking the art forms of her old country to her new one.

I too am following a trail from an old country to a less old one: the path of the golden Phra Bang Buddha. The statue was a present from the Cambodian king Jayavarman on the occasion of his daughter’s marriage to King Fa Ngum, who in 1353 founded the neighboring kingdom of Lan Xang—or Laos, as it is now called. Fa Ngum took the Phra Bang Buddha north to spread the Theravada branch of Buddhism in his country, and it was this Buddha that gave his royal capital its name: Luang Prabang.

Most people don’t even know where Laos is. Yet this landlocked country less than half the size of France looms large among Americans for one reason: Between 1962 and 1973, the CIA rained more than three million tons of bombs on Laos to stop the Vietnamese and Pathet Lao troops from bringing arms up the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The CIA successfully hid this war from the American people but failed miserably in its mission. Vietnamese troops kept marching on, and unexploded bombs remain to this day, maiming and killing a few Lao each year.

Laos has hardly known a moment of peace. It has been successively invaded by the Burmese, the Thais, the Vietnamese, the French, and finally the Americans. It was only in 1975 that the Lao People’s Democratic Republic was formed under French–educated Prince Souphanouvong. In 1994, the Australians built the Friendship Bridge between warring Thailand and Laos, and an uneasy peace prevails between the two neighbors. The routing of traffic over the bridge is itself emblematic of Thai–Lao relations: Thailand follows British road rules, while Laos sticks to the French system. As a result, there’s an awkward intersection in the center of the bridge where traffic on the right gets routed to the left, and vice versa. I avoid the confusion by flying into Vientiane from Phnom Penh on Lao Airlines.

Originally called Viangchan, or Sandalwood City, Vientiane could be mistaken for a village rather than a nation’s capital. The center of activity, at least for tourists, is Nam Phou Fountain, which is surrounded by restaurants and several Internet cafés. King Setthathirath moved his royal capital from Luang Prabang to Vientiane in 1560 and erected the revered That Luang Stupa, a phallic eyesore with way too much gold paint. King Setthathirath also built the more sedate Wat Ho Phakeo, which housed the famous emerald Buddha until the Thais looted the temple and installed the statue on the grounds of Bangkok’s Grand Palace. Most exquisite of all is Wat Sisaket, containing 6,840 Buddha images. It is prized because it survived the Thai rampage of Vientiane in 1828.

Rampage and restoration is a consistent theme in Vientiane. Lao silk, for instance, has long been celebrated for the quality of its weave, and now educated Lao and foreigners are working hard to reclaim that neglected heritage. Carol Cassidy, an engaging American who has spent much of her adult life in Laos, trains locals to weave Lao silk to world standards. At her workshop sit forty shy Lao women, clicking away on custom–designed looms to produce cushions, draperies, shawls, and wall hangings destined for America.

While enjoying a sunset drink at one of the makeshift restaurants lining the Mekong, I run into the South African couple who stood behind me in the airport visa line. Because Laos is a small country and most tourists follow the same itinerary, such coincidences are not uncommon. It is oddly companionable to see the same strangers again and again. So I gather tips from the Long Island woman who has “done” Asia many times over, avoid the English drunks who show up at every restaurant I visit, and share the flight to Luang Prabang with the German tour group I met on the way in.

Luang Prabang deserves its reputation as the jewel of Southeast Asia and a jet–set stop du jour. Even Henri Mouhot, the patronizing Frenchman who is often credited with “discovering” Angkor Wat, said that Luang Prabang reminded him of the beautiful lakes of Como and Geneva. “Were it not for the constant blaze of a tropical sun… the place would be a little paradise,” he wrote.

Bordered by the Mekong and Nam Khan rivers, Luang Prabang has Manhattan’s riverine geography but none of its frenzy. The town literally has three streets: one by the Mekong and another by the Nam Khan, with Royal Sakkarine Road in the center. There are no beggars and no traffic jams, in fact none of the maladies that plague most Asian cities. Rather, Luang Prabang is clean—and safe. When I ask for a lock to go with my rented bike, I am told that locks aren’t necessary because there are no thieves.

I am wandering through the golden stupas and gardens within the beautiful Wat Xieng Thong when an eighteen–year–old monk named Somphong appears, points at the dot on my forehead, and asks if I am Hindu. I nod. Suddenly excited, he leads me to the back and points at carved wooden panels depicting, yes, the Ramayana. The setting sun casts a dazzling glow on the gold leaf. Somphong grins triumphantly, and I try to feign surprise. “Wow,” I say, “the Ramayana.” Again.

As we walk outside, he tells me his story. He is from a mountainous province up north and joined the monastery to get an education. He plans to go to college and study astronomy, he says.

“Astronomy,” I repeat, as if it were perfectly normal for a saffron–swathed monk to aspire to NASA. “Any particular reason?”

“Come to the National Museum tomorrow and I will tell you,” he says cryptically.

Dawn brings one of the town’s most extraordinary sights. As the mist swirls, townspeople and tourists gather to give alms to a procession of five hundred monks, who pad barefoot through the silent streets in a blur of orange, saffron, and vermilion robes that conceal lacquer begging bowls. Devout Buddhists kneel and offer rice balls, spiced fish wrapped in banana leaves, fruit, cans of tuna, instant noodles, and even candy bars, which make the young novices break out in smiles. As the sun comes up, the monks disappear like ghosts into the monasteries to pray and study before eating their last meal of the day by noon.

Somphong meets me outside the National Museum at 2 p.m. He takes me to the room in front, which contains gifts from various governments to the Lao. There are Buddha figures and friendship flags, silver crucibles from the Thais, a pearl–inlaid rifle from the Soviets, and finally a moon rock given by President Nixon. Somphong points at the awkwardly shaped rock, no bigger than a fist.

“Next time, a Laotian will go on the moon and get that rock,” he murmurs. “Not receive it as a gift from the Americans.”

In Luang Prabang, the Mekong is never far, either physically or psychologically. Early one morning, I take a boat trip to the Pak Ou Caves, where successive Lao kings brought Buddhas to be consecrated. The musty caves are now lined with thousands of Buddhas, smiling beatifically at the huffing and puffing tourists. On the way back, I stop at Ban Xang Hai, or Jar–Maker Village, to sample the potent rice liquor known as lao–lao, stirred up by diminutive women who could outdrink an Irishman. I buy a few colorful Lao silk scarves, drawn as much by the round–eyed Lao children as by the ten–dollar price tag, before catching the longtail boat home.

In Laos, the Mekong becomes slow moving and languorous, spreading itself over banks planted with peanuts and cucumber. As the boatman poles us along, naked children dive into the coffee–colored waters, using car tires and rubber tubes as makeshift rafts. Women pan for gold, and men, standing knee–deep in the river, scrub water buffaloes.

I furtively drop my monk–inscribed dollar into the Mekong. The boatman yells and fishes it out. The monk who is bumming a ride home with me smiles mysteriously. I tell him about the Cambodian monk’s blessing. I have to drop the money in the Mekong, I explain, so that it will come back to me multiplied tenfold. The monk gazes at the bill, then turns it over and examines the writing closely. He says something in rapid, urgent tones. When I frown in confusion, he breaks into halting English. “This means ‘unfulfilled desire,’ not ‘money in Mekong,'” he says. “You must come back to fulfill your desire.”

I am unable to accept what I am hearing. Was the Cambodian monk playing a trick on me? Or has the meaning been lost in translation? I am not sure.

I carry the Pali–scripted dollar bill in my pocket to this day. It reminds me of the monk’s blessing and of the Mekong. Someday, I tell myself, I will go back and drop the bill into the river. And then I’ll be rich. The voice of the New Yorker inside me says, “Yeah, right. In your next life.”

END

Shobha I loved reading this. Immediately transcended me to Laos and Cambodia, can’t wait to visit now

Thank you Hiral