Recently, conservationists in Bengaluru had a huge win. The State Board of Wildlife, headed by the Karnataka chief minister, approved a proposal to deem 5,010 acre of grasslands, about 25km outside the city, as the Greater Hesaraghatta Conservation Reserve (GHCR). This was after successive chief ministers over a decade had rejected the proposal. Conservationists quietly rejoiced and waited for the official order.

A week after the news broke on 7 October, filmmaker Amoghavarsha J.S. posted an Instagram reel about his role in saving the Hesaraghatta grasslands. As a storyteller with over one lakh followers, Amoghavarsha said he was simply “sharing his happiness” at the news. There was one problem: Many felt the filmmaker, whose role had been minimal, was hijacking a conservation story that had involved an entire community and they hadn’t been credited or tagged. It brings up the question: Who owns the conservation narrative?

Siddharth Goenka, a former member of the Karnataka State Wildlife Board, says the proposal to give Hesaraghatta a Conservation Reserve (CR) status came from three petitioners in 2013: Hesaraghatta resident and photographer Mahesh Bhat, the late Ramki Sreenivasan, and Seshadri K.S., fellow-in-residence at Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (Atree).

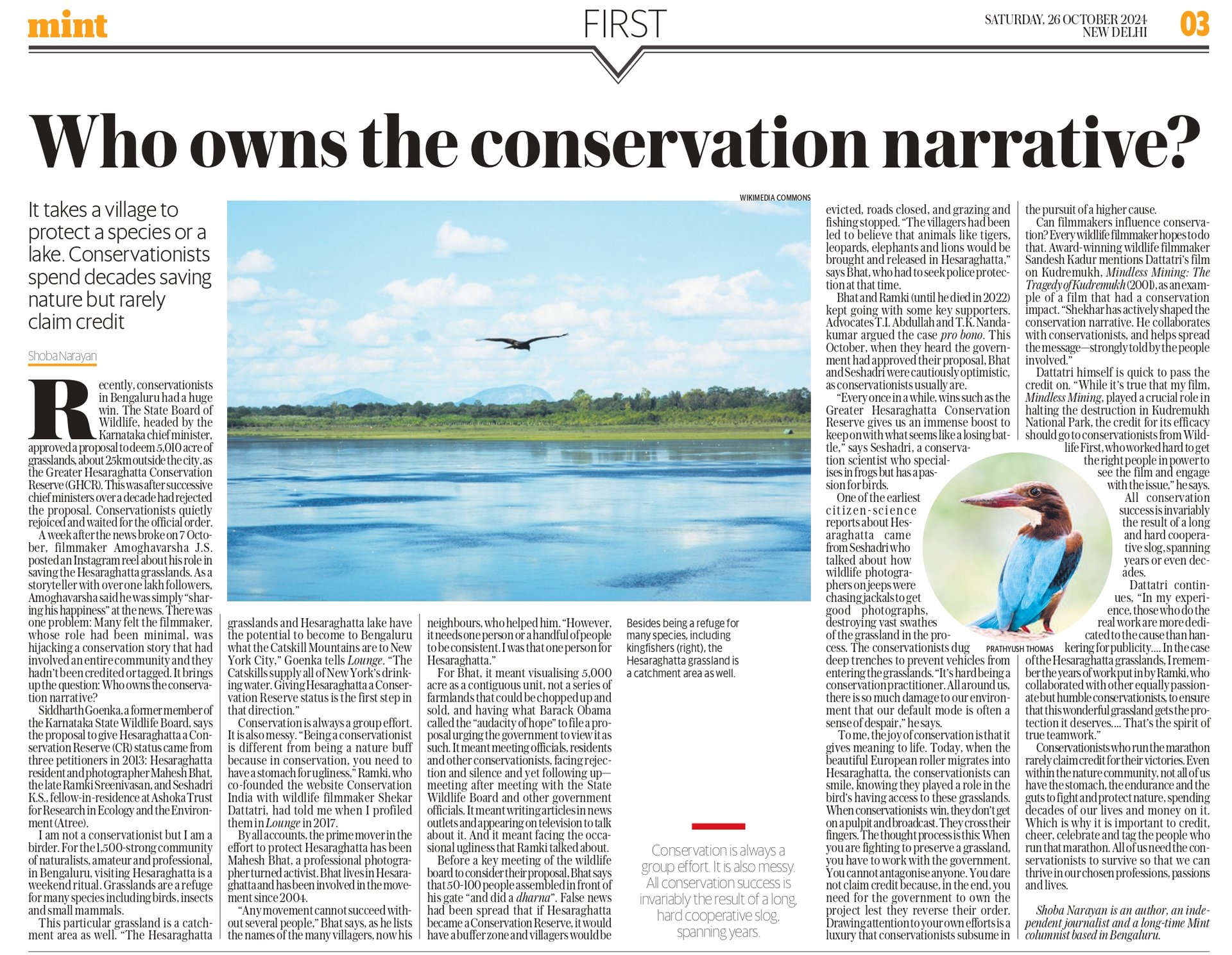

I am not a conservationist but I am a birder. For the 1,500-strong community of naturalists, amateur and professional, in Bengaluru, visiting Hesaraghatta is a weekend ritual. Grasslands are a refuge for many species including birds, insects and small mammals. This particular grassland is a catchment area as well. “The Hesaraghatta grasslands and Hesaraghatta lake have the potential to become to Bengaluru what the Catskill Mountains are to New York City,” Goenka tells Lounge. “The Catskills supply all of New York’s drinking water. Giving Hesaraghatta a Conservation Reserve status is the first step in that direction.”

Conservation is always a group effort. It is also messy. “Being a conservationist is different from being a nature buff because in conservation, you need to have a stomach for ugliness,” Ramki, who co-founded the website Conservation India with wildlife filmmaker Shekar Dattatri, had told me when I profiled them in Lounge in 2017.

By all accounts, the prime mover in the effort to protect Hesaraghatta has been Mahesh Bhat. Bhat lives in Hesaraghatta and has been involved in the movement since 2004. “Any movement cannot succeed without several people,” Bhat says, as he lists the names of the many villagers, now his neighbours, who helped him. “However, it needs one person or a handful of people to be consistent. I was that one person for Hesaraghatta.”

For Bhat, it meant visualising 5,000 acre as a contiguous unit and having what Barack Obama called the “audacity of hope” to file a proposal urging the government to view it as such. It meant meeting officials, residents and other conservationists, facing rejection and silence and yet following up—meeting after meeting with the State Wildlife Board and other government officials. It meant writing articles in news outlets and appearing on television to talk about it. And it meant facing the occasional ugliness that Ramki talked about.

Before a key meeting of the wildlife board to consider their proposal, Bhat says that 50-100 people assembled in front of his gate “and did a dharna”. False news had been spread that if Hesaraghatta became a Conservation Reserve, it would have a buffer zone and villagers would be evicted, roads closed, and grazing and fishing stopped. “The villagers had been led to believe that animals like tigers, leopards, elephants and lions would be brought and released in Hesaraghatta,” says Bhat, who had to seek police protection at that time.

Bhat and Ramki (until he died in 2022) kept going with some key supporters. Advocates T.I. Abdullah and T.K. Nandakumar argued the case pro bono. This October, when they heard the government had approved their proposal, Bhat and Seshadri were cautiously optimistic, as conservationists usually are.

“Every once in a while, wins such as the Greater Hesaraghatta Conservation Reserve gives us an immense boost to keep on with what seems like a losing battle,” says Seshadri, a conservation scientist who specialises in frogs but has a passion for birds. One of the earliest citizen-science reports about Hesaraghatta came from Seshadri who talked about how wildlife photographers on jeeps were chasing jackals to get good photographs, destroying vast swathes of the grassland in the process. The conservationists finally had the government dig deep trenches to prevent vehicles from entering the grasslands. “It’s hard being a conservation practitioner. All around us, there is so much damage to our environment that our default mode is often a sense of despair,” he says.

To me, the joy of conservation is that it gives meaning to life. Today, when the beautiful European roller migrates into Hesaraghatta, the conservationists can smile, knowing they played a role in the bird’s having access to these grasslands. When conservationists win, they don’t get on a pulpit and broadcast. They cross their fingers. The thought process is this: When you are fighting to preserve a grassland, you have to work with the government. You cannot antagonise anyone. You dare not claim credit because, in the end, you need for the government to own the project lest they reverse their order. Drawing attention to your own efforts is a luxury that conservationists subsume in the pursuit of a higher cause.

Can filmmakers influence conservation? Every wildlife filmmaker hopes to do that. Award-winning wildlife filmmaker Sandesh Kadur mentions Dattatri’s film on Kudremukh, Mindless Mining: The Tragedy of Kudremukh (2001), as an example of a film that had a conservation impact. “Shekhar has actively shaped the conservation narrative. He collaborates with conservationists, and helps spread the message—strongly told by the people involved.”

Dattatri himself is quick to pass the credit on. “While it’s true that my film, Mindless Mining, played a crucial role in halting the destruction in Kudremukh National Park, the credit for its efficacy should go to conservationists from Wildlife First, who worked hard to get the right people in power to see the film and engage with the issue,” he says.

All conservation success is invariably the result of a long and hard cooperative slog, spanning years or even decades. Dattatri continues, “In my experience, those who do the real work are more dedicated to the cause than hankering for publicity…. In the case of the Hesaraghatta grasslands, I remember the years of work put in by Ramki, who collaborated with other equally passionate but humble conservationists, to ensure that this wonderful grassland gets the protection it deserves. Had he lived to see this dream come true, I know he would have downplayed his role and acknowledged everyone else’s contribution. That’s the spirit of true teamwork.”

Conservationists who run the marathon rarely claim credit for their victories. Even within the nature community, not all of us have the stomach, the endurance and the guts to fight and protect nature, spending decades of our lives and money on it. Which is why it is important to credit, cheer, celebrate and tag the people who run that marathon. All of us need the conservationists to survive so that we can thrive in our chosen professions, passions and lives.

Shoba Narayan is an author, an independent journalist and a long-time Mint columnist based in Bengaluru.

-k4lD-U204025897261YmH-250x250%40HT-Web.jpg)

Leave A Comment