Those who still call space “the final frontier” have clearly not experienced the sea—vast, deep, mysterious. For humans, the sea is the ultimate other, requiring adaptations that seem intuitive but actually are not. There are three kinds of people in the world—those who feel “at home” in the water, those who don’t, and a large group in the middle (including me) who view open water with a mixture of awe, fear and pleasure.

India with its 8,000 kilometres of coastline is particularly suited to “water babies” you would think, but you would be wrong. Go to the beach in most cities and you will see folks sit gingerly on the sand without venturing into the sea. That seems to be changing—Goa boasts a community of open water swimmers who regularly go into the Arabian Sea to swim as a group. Bengaluru, despite being landlocked, has a community of scuba divers who travel to different parts of the world to dive. Sports shops routinely sell snorkelling gear to city slickers.

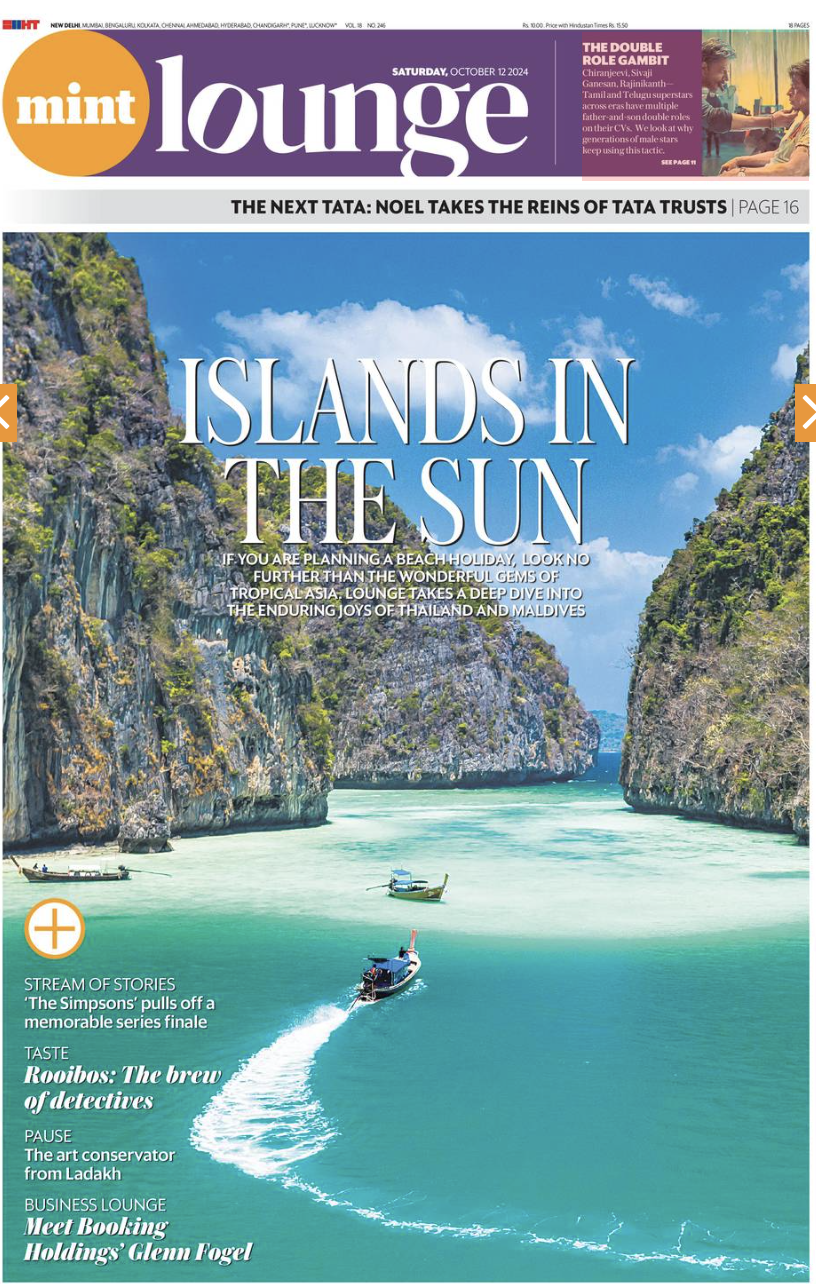

All of this crossed my mind as I waded into the turquoise waters of the Maldives with my snorkelling gear—mask and flippers. For Indians who engage with open water on a regular basis, the Maldives are a no-brainer. “The atolls are safe, the currents are gentle, you get to see large marine animals like sharks and manta rays because visibility is great,” says Bengaluru-based Nikhil Chengappa, who has trained over 2,000 people in scuba diving through his company, Fleetfoot Adventures.

I learnt scuba diving in the Maldives, although these days, I mostly snorkel. If you are with family or friends who are not crazy about diving, snorkelling is a great option because it allows you to engage with marine life in a way that doesn’t overwhelm. Just outside my cottage at the Soneva Fushi resort, for instance, was a coral reef. Several times a day, I walked out into the sea and start swimming with my flippers. A few feet away was a deep drop. This edge between shallow water and a deep trench is the sweet spot for snorkelling. Unlike diving, snorkelling doesn’t require too much gear or preparation. A German guest I befriended at lunch got up after dessert, wore her flippers and jumped off the floating restaurant into the water to snorkel. She was going to follow the reef around the island, she said.

The allure of snorkelling is this on-off agility. On the day we arrived, my husband had no desire to jump into the water. He sat reading on the beach, while I waded in. I saw about 20 species of marine life, including a small shark, which breezed past at the edge of my eyeline. Sharks are the tigers of the marine ecosystem. If there is a healthy population of sharks, you know that all is right. Beginning snorkellers usually require supervision but soon learn that if you treat marine life with respect and keep a safe distance, you can snorkel alone, particularly if you are near land.

On another day, we went on a snorkelling trip to Noonu Atoll near Soneva Jani, a sister property. Our guide was AJ, a Maldivian training to be a free diver. I asked him how long he could hold his breath underwater. “Two minutes,” he replied and demonstrated by removing his snorkel gear and diving deep into the darkness. It was scary to watch, let alone do, but for divers, the action lies deep within the bosom of the sea, for this is where one encounters turtles, eels, and if you are lucky, an octopus.

The most important skill one needs in order to engage with open water is the ability to slow down one’s breath. You need to do this when you scuba dive or free dive. Snorkelling is easier because you have the breathing tube that stays above the water. But the sea always holds surprises. When I jumped into the sea from the boat, the water was cooler than I anticipated and rougher—even in gentle seas like in the Maldives. The best way to deal with this new environment is to take slow breaths and mimic the graceful micro movements of the fish you see. When I snorkel, I can go for 20 minutes— floating in one spot, watching the fish duck in and out of the colourful coral—swimming below me in choreographed schools. These coral reefs are vital for marine life, and are of huge importance not just for the swimming and diving community but also for tourism in the Maldives.

Sonu Shivdasani, the British founder of Soneva, has set an ambitious goal. “Scientists say 90% of the coral that exists today will have died by 2030—in only six years,” he says. “Our goal is to bring our reefs back to the state that Eva (Malmstrom; his Swedish wife) and I remember from our first visit to the Maldives in the 1980s.” Born to wealth, Shivdasani and his wife travelled around the world for their honeymoon before choosing the Maldives to start their luxury hotel venture in 1995 by combining their names into a brand— Soneva. Today, Shivdasani has turned his brand-focus into wellness, and speaks and writes often and publicly about being a cancer survivor and of his commitment to coral regeneration.

The good news is that several luxury brands like the Four Seasons, Baglioni, Anantara and Soneva are making efforts to restore the coral reefs by growing new coral. Solène Jonveaux, from France, is the assistant manager of the Soneva Coral Project. She talked about techniques like mineral accretion technology (MAT) and micro-fragmentation to rapidly grow and transplant resilient coral colonies. In plain English, this means growing coral in controlled conditions before releasing them into the ocean. At their coral spawning and rearing lab, we were shown tiny polyps that were being grown over weeks in bubbling tanks before a team of scuba divers would transplant them into the sea. Subconsciously, I had lumped coral with marine flora—they looked like stationary plants to me. I learned, somewhat sheepishly, that corals are actually part of marine fauna—they are invertebrates.

At Soneva Jani in Baa Atoll, my husband and I snorkelled at the house reef and found metal tables on the sea floor where new coral was growing. It is a delicate and pain-staking process because it requires specific conditions for the zooxanthellae which provides “food” for coral growth inside the polyps to thrive. Mother nature creates these conditions effortlessly until we humans go and muck them up. “If the conditions aren’t right, the zooxanthellae will abandon the polyps causing it to die,” said our tour guide.

Without coral, the sea loses its colour and much of the marine life that transfixes us humans. Island nations like the Maldives with a huge influx of tourists seeking to dive and snorkel on their seas depend on the beauty of corals to keep up their economy. Several partnerships between the Maldives government and luxury resorts have been fostered to ameliorate the devastating effects of global warming and the El Niño currents. For resorts like Soneva Jani, where the overwater villas literally sit over the sea, coral reefs are an essential part of their charm. It is what brings people to the place. Says Gerhard Stutz, the German general manager of Soneva Fushi, “For resorts like ours that are part of the fragile marine ecosystem in the Maldives, sustainable tourism cannot just be about reusing towels. It has to be about regenerating our waters.”

On my last day, as I snorkelled in the house reef at Soneva Jani, I floated about the metal tables and observed tiny coral polyps waving in the currents. They were of different sizes. Having seen them in the lab, I could tell which ones were the “babies,” just a few weeks into the water, and which were the older ones with larger polyps. Already fish were swimming around the polyps attracted by the small invertebrates that it had spawned. Soon the manta and eagle rays would show up and then the sharks. The circle of life—in this tiny part of the Indian Ocean—would begin again.

Shoba Narayan is an independent writer based in Bengaluru and has been a long-time contributor to Mint.

Shoba Narayan is Bangalore-based award-winning author. She is also a freelance contributor who writes about art, food, fashion and travel for a number of publications.

-k4lD-U204025897261YmH-250x250%40HT-Web.jpg)

Very interesting!