Can India’s Silicon Valley make it as a megacity?

Sometimes, in Bengaluru, you still feel you’re in a small town. The cantonment area, where Indian military barracks have replaced the British army’s, retains some of the green spaciousness (and English street names) of colonial times. Bengaluru’s famously gentle climate, India’s best, with temperatures rarely exceeding 30C, helped persuade the British to set up here. The cantonment’s roads were built for the occasional officer’s car, and for cycling Indians.

But today those roads are jammed with traffic. In 2022, Bengaluru had the world’s second most congested city centre (after London), calculated satellite navigation maker TomTom. Bengaluru has shot from about 700,000 inhabitants at independence to 14 million or so today, far more than London or New York. The population has doubled just since 2005 — stunning growth even for a developing-world city. To the western visitor, Bengalureans look weirdly young: India’s median age is 28.

The one-time sleepy southern “Pensioner’s Paradise”, where shops opened late, has become “India’s Silicon Valley”. It feels as dizzyingly dynamic as Manchester must have mid-Industrial Revolution. Now Bengaluru has reached a fork in the packed road: will it become a superstar city like New York or a dysfunctional one like Mumbai? Success will require handling the challenges facing all developing cities: tame the traffic, protect the local environment, cope with climate change and allow migrants from different places to live together in peace. Bengaluru’s history as a tech hub goes back to 1909, when the now world-beating Indian Institute of Science was founded. Countless educational institutions followed, and today the city’s talent works in start-ups, call centres, the research centres of global companies or the headquarters of Indian tech corporations like Infosys. Each new software developer creates jobs for maids, waiters and delivery riders, so Bengaluru expands, almost daily, through both gated communities and slums.

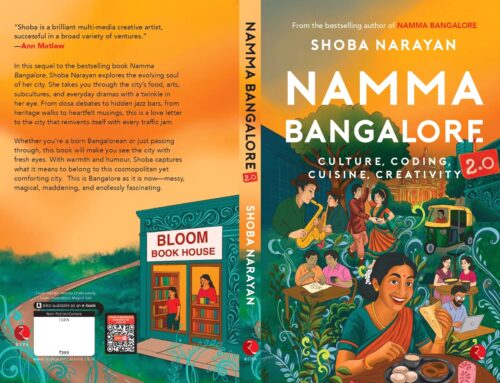

Migrants change a city, and the city changes them. In a functioning metropolis, new arrivals don’t merely get richer. They fulfil themselves in ways they couldn’t back home. “In Bengaluru, you can weave your way through the traffic and find yourself,” said author Shoba Narayan at this month’s Bangalore Literature Festival, where youthful crowds were another sign of the city’s cultural blossoming.

One young migrant, a woman from Kolkata, told me: “Youngsters make the rules here.” In historically tolerant Bengaluru, they can live in sometimes mixed-gender flatshares, flirt in the bookshops on Church Street, go on dates in the city’s booming pub scene and make their own marriage markets away from their parents. Women here can wear jeans and T-shirts, and go out at night with less fear than in Delhi.

Bengaluru’s problem is liveability. The city is “crumbling under its own success”, write Malini Goyal and Prashanth Prakash in Unboxing Bengaluru. The one-time “garden city” is now often redubbed the “garbage city”. The vast majority of its famous lakes have been built over, threatening drinking water supplies. The rich are cordoning themselves off in new suburbs, diluting what should be the creative alchemy of a great city. These suburbs need to become accessible hubs, so that Bengaluru can acquire multiple centres faster than Paris or London did.

Bengaluru’s advantage is its late expansion. That means it can avoid the blunders of 20th-century megacities, which remade themselves for cars only to find that the endless flyovers ruined liveability and ended up clogged too. Cars can be a solution for small towns, but cities of millions can’t squeeze them in. Bengaluru’s subway only opened in 2011, but it’s expanding fast. The city needs to construct almost immediately the local rail infrastructure that London built over nearly two centuries. The logical complement would be bike lanes — a return to India’s cycling past — but these now seem unthinkable, as the cars leave no space.

Some great cities won’t survive climate change. Bengaluru starts from a better place than boiling, smog-clogged Delhi or flood-prone coastal Mumbai, but the heat is worsening here. Last year was the city’s wettest on record.

All multicultural cities face another threat: ethnic conflict, especially in Narendra Modi’s Hindu-supremacist India. By 2011, 107 languages were spoken in Bengaluru, the highest number in India. Some Kannada-speaking locals, nostalgic for their lost paradise, grumble about the newcomers, especially poorer migrants from northern India.

Good governance could manage these problems, but good governance isn’t a Bengaluru tradition. It’s probably already too late for the city to become a New York. But there’s still time to do better than Mumbai.

Leave A Comment