I am wrestling with the whole notion of culture, identity, tradition, aesthetics, and how to infuse them into my life. How to embody these things? By wearing a sari? After years of being an atheist and then becoming a agnostic, I am taking baby steps to the other side. Someone– Pratap Bhanu Mehta, I think– wrote a nice piece a while ago, stating that you can be religious and secular at the same time. I come from a religious family. I have rebelled against it all my life. Now, slowly I am trying to see the merit in it. I am doing navarathri (golu) for the first time this year (with sincerity rather than snarkiness and scorn). Trying to chant– mostly because meditation is too hard. Trying to follow the specific/regional aesthetic of my mother. Not sure whether I will go back to my skirt-and-boots wearing days or see that the glove actually fits.

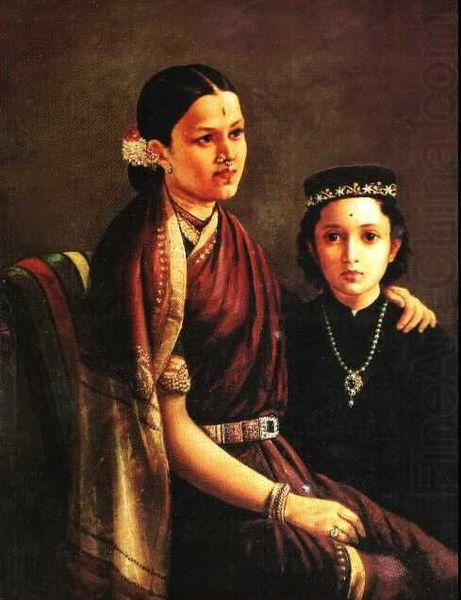

Here is a piece in which I have tried to get other womens’ gyan on this idea. Love the Raja Ravi Varma painting that goes with this. Let me clarify, as a painter, I don’t think Raja Ravi Varma was very good. He was a portrait painter– not original. Copied ideas from the English and Dutch painters. His paintings are like Vermeer, or Rembrandt. But I love the aesthetic that he portrays. So am including some of my favorite photos of his in this link. Below is my favorite of his paintings because it portrays the Indian notion of beauty so nicely. Straight parting, round face, calm eyes. Notice the blouse style. Notice the casual drape of the sari. Not the jewels.

Below is another favorite. I love the way the sari is draped around the shoulder. M.S Subbulakshmi did the same thing as did my grandmother.

When one lens views it all

Today, most cultures emulate the catwalk notion of beauty, which in turn is largely defined by American and French fashion

Shoba Narayan

First Published: Sat, Sep 28 2013. 12 10 AM IST

![Raja_Ravi_Varma,_Galaxy_of_Musicians[1]--621x414](https://shobanarayan.com/cdn-cgi/imagedelivery/6XNcUQBAHMs3VCC3obG3FQ/shobanarayan.com/2013/09/raja_ravi_varma_galaxy_of_musicians1-621x414-4.jpg/w=621)

A Raja Ravi Varma painting shows Indian women dressed in regional attire. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

At a time when the Indian-American winner of the Miss America contest has evoked ire and hate mail online, it seems appropriate to talk about notions of beauty. Japanese culture valued the nape of the neck as a woman’s most beautiful feature: Witness the low collar of the kimono in the back. Chinese culture has fairly specific ideas of what constitutes a beautiful woman—eyebrows arched like willow leaves and lips that are soft and pouty like a rosebud are but two of them. All these are ancient cultural prescriptions. Today, most cultures emulate the catwalk notion of beauty, which in turn is largely defined by American and French fashion.

In his book, Monoculture: How One Story Is Changing Everything, author F.S. Michaels explores how most of the dominant ideas of today are seen through the prism of economics. In fairly Orwellian terms, Michaels describes his thesis as: “The governing pattern a culture obeys is a master story—one narrative in society that takes over the others, shrinking diversity and forming a monoculture. When you’re inside a master story at a particular time in history, you tend to accept its definition of reality. You unconsciously believe and act on certain things, and disbelieve and fail to act on other things. That’s the power of the monoculture; it’s able to direct us without us knowing too much about it”.

The economic monoculture that Michaels talks about has far-reaching impact on everything from creativity to culture to aesthetics.

Recently, I posted a query on a terrific Bangalore-based “secret” Facebook group, called The Friday Convent, about regional Indian dressing styles. What did your grandmother wear, was the question. The range and specificity of the responses was thrilling in its plurality. Here is a sample, edited for space.

Saritha Hegde: Bunt women from Mangalore wore eight-stone diamond earrings with gold, sari tied slightly short, centre parting, bun, puffed-sleeve blouse, nose-rings and toe-rings, gold bangles and most importantly, the karyamani, i.e. the black beaded mangalsutra. Interestingly, the bride’s mother ties the mangalsutra on the bride the night before the marriage. We are a matrilineal community.

Sheena Agarwaal: Being a Rajasthani Baniya, my grandmother was adorned in a chaniya choli. Head covered. Tattooed around the chin and sides of the temple (apparently a sign of puberty), red and green bangles made of glass. Toe-ring. Anklets. Earrings that had this string to be hooked to the hair. In all, as we say, solah sringar!

Suhasini Rao-Kashyap: As for the Maharashtrian nine-yard—there are three major versions—the brahmin (Deshasta and Konkanstha), the Deshavarchi (Marathas) and the Koli fisherwomen. The first is what you’ll mostly see on telly in Jhansi ki Rani type serials. Distinguishing features—worn paay-ghol (touching the toes). There is a kashta (the bunch of pleats at the waist) and a padar (dupatta) that is long and covers the shoulders, like a shawl. The deshavarchi nav-vaari (nine-yard) is trimmer. Silk is common amongthe better off. Usually a kambar-patta (cummerbund or gold belt) of heavy, solid gold is worn over the sari. The last one—kolniwada—is worn at the knees. Usually cotton, for obvious reasons. Legs are left free, to wade through water while dealing with the fish.

Anne Helena Devasahayam: Christian Nadar women from Tirunelveli, Tamil Nadu, and the surrounding areas wore handwoven silk/cotton saris. Neatly parted, oiled hair tied in a low bun. Elegant gold attigais. Large, long ear piercing with heavy gold earrings.

Sudha Mathew: Kerala Syrian Christian ladies till my grandmother’s generation wore only white. They wore a plain white blouse called the chatta, which came till the waist and a seven-yard-long piece mundu that was worn in such a way that there would be a fan like pleating at the back. No midriff showing! When they went out, they wore another peace of white cloth called the kavani over the chest, much like a dupatta. Imagine wearing white all the time! However the way they tried to differentiate was the material of the kavani. For special occasions, ladies would use very fine materials for the kavani to stand out from the crowd, sometimes sourced from abroad…. Only from my mum’s generation, they started wearing saris. Another thing that is still more or less observed in the Syrian Christian community is a preference for wearing white or pastel saris to church, especially in Kerala…. The Kerala Muslim and Hindu women also wore something similar to the chatta-mundu. Except that the Muslim women wore a white headdress and more colourful blouses and the Hindu mundus had a line of colour at the edges.

Rubina Guleria: A Kumaoni Rajput, from Nainital, Uttarakhand. Kumaoni women wear a neckpiece like a choker called guloband and chunky bracelets called paunchee—which are gold beads like the Coorgi gold beads woven in tight bracelet. A full cover blouse with sleeves and sidha pallah sari. Massive nose-ring and sindhoor right over to the nose at times. Kumaoni women wore real bright colours and had their head always covered, and wore the nath (nose-ring).

Minal Hajratwala: The Gujarati style of sari is worn with the pallu in the front. My great-grandmother was a widow and therefore wore only white cotton and a cotton blouse which was string-tied in the back (no hooks, etc.).

Aparna Raman: My grandmother wore a Kanjeevaram nine-yard sari called madishaar, she wore nose-rings on both sides and the traditional four-clove diamond called thodu as earrings. Toe-rings, called metti, were a must. The forehead had to be always decorated with a pottu. In Karnataka, green bangles are popular and very traditional Bengali married women, from what I remember of my childhood, wore red and white bangles and a loha (iron) bangle.

Priya Sunder: My grandmother was a Tam-Brahm brought up in Maharashtra, but lived in Varanasi after marriage. She wore her sari the Maharashtrian way (with the sari going between her legs), cooked Banarasi- and UP-type foodat home, spoke Tamil and wrote letters in Hindi.

The aesthetic of The Friday Convent is largely Western. At events, women wear shift dresses and scarves; slim-fit jeans and boots. But their comments tell me that India’s sartorial past still resonates with them; the soft silks and intricate jewellery that are our birthright and aesthetic oeuvre still tug at our hearts. Next week, I plan to visit Kalakshetra in Chennai to see it in action.

Shoba Narayan abhors monoculture.

Shoba one of my friends recently shared that his wife (also an arts graduate turned homemaker) had lately begun to explore all sorts of Asian (including Indian) things. It struck me as a similar theme – kids now growing up into independent personalities and parents not being able to “keep up”, as it were, hence all the arguments etc.

My friend told his wife she was perhaps “losing her grip” (meaning attention, not control), and after a long discussion she agreed. In the early years she was “fully needed” i.e. to take care of the kids etc – stuff her husband could not really do, then she became “mostly needed”, again to sort of handle the home – organize office and birthday parties, play dates, events and such, and then she became “occasionally needed” – to when the kids “needed” to talk but otherwise were in a wholly different direction than parents, and finally, when kids were mostly self sustaining, she became “rarely needed”.

My friend suggested she pick up a proper hobby that would channel and utilize her talents, but she replied, “the hobby won’t really *need* me, either.”

Sad, I thought, but true.

I hope the lady finds her bliss, Naina.