Shoba Narayan prepares a meal.

‘Monsoon Diary: A Memoir with Recipes’ Shoba Narayan’s Book Celebrates Family and Food

Shoba Narayan tastes a recipe in her New York City kitchen.

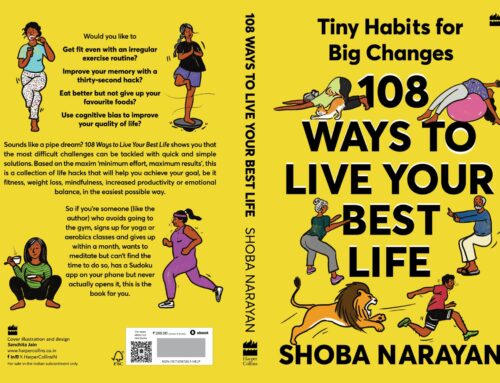

Cover for Narayan’s book, ‘Monsoon Diary: A Memoir with Recipes’ (Villard Books)

Narayan prepares vegetable dosa for lunch.

The world of author Shoba Narayan is a rich mixture of her native India and her adopted home, America. Narayan has written about her journey from southern India to the United States in her new book

Monsoon Diary: A Memoir with Recipes. Narayan tells NPR’s Lynn Neary that cooking was part of her destiny — she absorbed the secrets of southern Indian cuisine watching her mother and grandmother prepare meals, and also learned much about her family and her world by observing the relationship between Indians and food. “And when she decided she wanted to attend college in the United States, it was cooking which sealed her fate,” Neary says. “Her family didn’t want her to go. After endless arguments, an uncle suggested a solution — make a feast.” The meal was so good, Narayan says, her family finally consented. Narayan’s house is filled with the aroma of Indian spices. Her kitchen is typical of a New York City apartment — small, yet filled with all the modern conveniences. Sometimes, she says, all the conveniences take away from the tactile experience of authentic Indian cooking. But the spices always remind her of her true roots.

“All Indian cooking, says Narayan, begins with the spices. She has an entire kitchen cabinet filled with spices — many of them are homemade, sent to her from India by her mother,” Neary says. Family is the central theme of Narayan’s cooking, and also

Monsoon Diary. Food and recipes, like family ties, are celebrated for their life-affirming qualities. Much more than a cookbook,

Monsoon Diary is a reminder of how food is as much a vehicle of culture and identity as language and history. Below, an excerpt from

Monsoon Diary, with a recipe for ghee, the clarified butter that is a staple of the Indian diet and a signature flavor in many Indian dishes: “Ghee is the vegetarian’s caviar: slightly sinful, somewhat excessive, but oh so delicious. For Indians, ghee offers the same rich — if guilty — pleasures that chocolates do for the dieter. My sister-in-law Priya is known far and wide as an exceptional cook. She says that just a teaspoon of ghee makes all the difference in flavor — like ice cream versus fat-free sorbet. While Indians may skimp on ghee in their daily life, they go overboard when it comes to ghee sweets. Bus travel through Rajasthan, Maharashtra, and most other North Indian states affords the particular pleasure of eating hot rotis (flat breads) made right before one’s eyes at tiny roadside stalls and served on banyan leaves with a dash of hot ghee on top. These rotis are made from different grains — bajra, jowar, ragi — each with its own distinctive taste. But they are all topped with ghee. Ghee keeps at room temperature for about two months, longer in the winter. It should be used like a condiment, in small quantities. Indians typically brush ghee on their breads, spoon it into rice, or stir it into their soups. Makes about 1/2 cup 2 sticks (1 cup) unsalted butter, cut into 1-inch pieces 1. Bring butter to a boil in a small heavy saucepan over medium heat. 2. Once foam completely covers the butter, reduce the heat to very low. Cook, stirring occasionally, until a thin crust begins to form on the surface and milky white solids fall to bottom of pan, about 8 minutes. 3. Continue to cook, watching constantly and stirring occasionally to prevent burning, until the solids turn light brown and the butter deepens to golden and turns translucent and fragrant, about 3 minutes. 4. When the ghee stops bubbling, you can safely assume that it’s done. Remove it from the heat, let it cool, and pour it into a jar.”

Leave A Comment