Does science displace myth? And if so, should we care? Chandrayaan discovered water on the fifth largest satellite in the solar system and all of us in Bangalore—home to Isro—are over the moon.

Does science displace myth? And if so, should we care?

Chandraayan discovered water on the dark side of the moon and all of us in Bangalore—home to ISRO—are over the moon. While I marvel at India’s magnificent achievement in the space program, a part of me is also a tad sad. This, I guess, is where the arts and the sciences diverge. The arts are about imagery and storytelling; myth and mystique. The sciences are about the pursuit of truth. The truth is irrelevant to storytelling; and storytelling is anathema to fact-based science.

Very few objects become the nexus where the arts and sciences converge. Atoms, for instance, fascinate scientists but hold little interests to poets. Ditto for global warming, biochemistry, epidemics, and DNA, all of which made recent headlines in science journals, but scarcely made an appearance in the arts. Economics is the wildcard as David Hare’s play, ‘The Power of Yes,’ on the global financial crisis eloquently proves.

The moon, I would argue, is the exception to this art-science dichotomy. It has fascinated scientists and philosophers, astronomers and astrologers, poets and politicians. In demystifying the moon, are astronomers reducing it from a poet’s allegory to a mere astronomical object?

The Japanese held moon-viewing parties that Lady Murasaki described in what some call the world’s first novel, ‘The Tale of Genji.’ Chinese poetry is full of allusions to the moon— as a friend to the lovelorn and as an illusion that disappears after a drink. Li Bai, an ancient poet of the Tang dynasty, talks about raising his cup and beckoning the moon. “My shadow included, we are a party of three,” he said.

The moon, when you think about it, is a minor player in the galaxy. Comets, black holes and meteors are more complex and convey more force and influence. The reason the moon is important to earthlings is because of its geographical nearness; and the fact that we have always fantasized about colonizing it. The moon’s size and its dynamism make it compelling to us. It does things: waxing, waning, disappearing, reappearing. It is huge when compared to the stars and even though, we know that this is because the stars are farther away from the earth, we still cannot comprehend this galactical distance. Most of all, the moon is beautiful. It is distinct— easily spottable in that vast eternity that is the universe. So we worship it, stare at it, dream about it, keep healing crystals under its benevolent light. The moon is cool— both literally and figuratively. We chart our travels based on it; propitiate ancestors when it disappears; map tides and a woman’s hormones according to it.

For all these reasons, the moon occupies a disproportionate stature in poetry, music, verse, theater, paintings and our own psychic space. So much so that when Greek philosopher, Anaxagorus, first suggested that moon fed off the sun’s light, he was imprisoned and later exiled for removing the romance from the heavens. In partial apology, astronomers named a crater on the moon after him.

Vedic astrology, if I am not wrong, is based on the lunar calendar. This unpredictable tractable creature that Vedic sages called Soma— son of Atri and Anusuya— created many myths ranging from Rahu swallowing the moon to Ganesha cursing the moon.

Other scientific displines may arouse ire but not this level of romantic nostalgia as the moon does. Genetics, for instance, is drilling into our bodies and discovering that we Indians are neither Dravidian nor Aryan; that there is no North-South divide. We are– contrary to caste and religious predilictions—all mixed up. This recent landmark study by a team of Indian and Harvard scientists offers provocative conclusions but inspires little romance. The moon is the ultimate romantic tool. Health Minister Ghulam Nabi Azad said that television could reduce population growth. But how to control desires that waxed and waned on a coir bed under the light of the moon?

Until television became babysitter and distraction, much of India was fed under the moon. Crying infants were taken outside, securely tucked around the hip of an obliging aunt. Unenticing morsels were then thrust into the reluctant infant’s lips using the moon as distraction. ‘Ambuli kaati amudhu padaithu,’ goes a famous Tamil dialogue and it means ‘I showed you the moon and fed you nectar.’ Today, Tom and Jerry play that role.

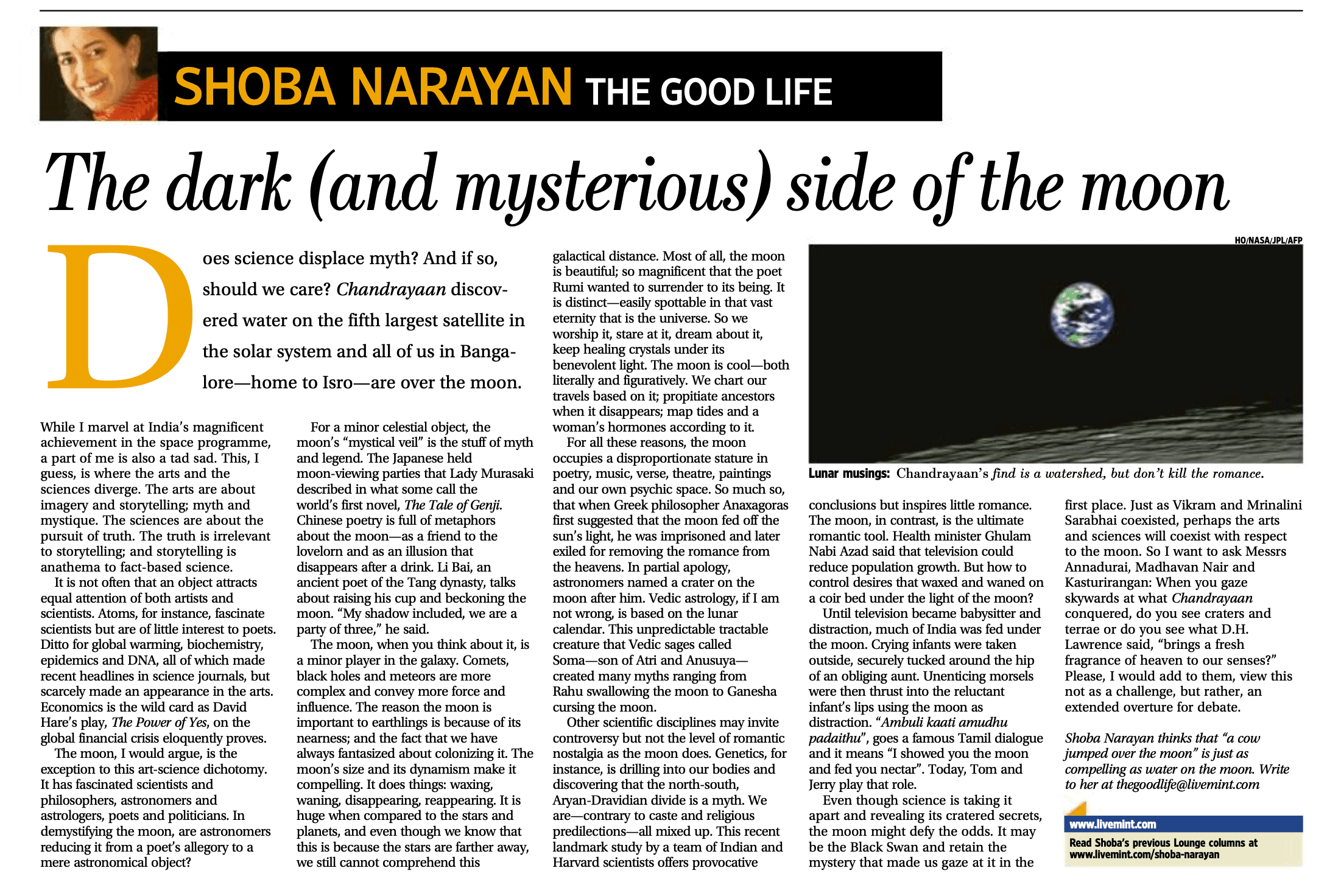

Even though science is taking it apart and revealing its cratered secrets, the moon might defy the odds. It may be the Black Swan and retain the mystery that made us gaze at it in the first place. Just as Vikram and Mrinalini Sarabhai coexisted, perhaps the moon will remain fascinating to both scientists and artists. So I want to ask Messrs. Annadurai, Madhavan Nair and Kasturirangan: when you gaze skywards at what Chandraayan conquered, do you see craters, terrae and riboleths or do you see what D.H. Lawrence said, “brings a fresh fragrance of heaven to our senses?”

Shoba Narayan thinks that ‘a cow jumped over the moon,’ is just as compelling as water in the moon.

4 min read . Updated: 01 Oct 2009, 09:27 PM IST

Leave A Comment