Is there an Indic approach to leading a good life? I asked some scholars who are part of an online group called “Bharatiya Vidwat Parishad,” focusing on Indic thought. Here below is a compilation of their answers along with my own thoughts.

Early humans, whether in Egypt, China or India venerated and propitiated nature because their survival depended on it. They worshipped the sun god, fire and wind. So too in India, where early Vedic hymns worshipped the earth, water and fire. Should we return to this approach, especially given that Mother Nature is showing her temper by unleashing cyclones, forest fires and melting glaciers? Should we view nature with the same reverence that our ancestors did– as a powerful being that needs to be cared for and propitiated? To me, putting the sacred back into our relationship with nature will give an added fillip to our efforts to stave off climate change.

Besides nature, the umbrella against which the good life is measured in Hinduism are the four purusharthas: dharma, artha, kama, and moksha. Dharma is difficult to translate, but let us call it purpose. Artha means prosperity, not just monetary but also abundance in all its aspects. Kama is love and pleasure. Moksha is salvation from the vagaries of human existence. These four worthy goals intertwined with the idea of timing or the four ashramas (stages) of life set the cadence for a life well-lived. Do what you need at the right time. When you are a student, study. Once you have fulfilled your duties as a householder, retreat to the forest.

These are macro concepts linked to life-cycles. What about simple material wishes about promotion, business victories and the kind that we look to self-help books for? These things are covered in the tail-end of many Hindu texts, according to Nagaraj Paturi, Dean, Indica. They are called ‘phala shruthis’ or a list of blessings that you get by chanting a certain powerful strotram or hymn. For example, the Lalitha Sahasranamam or the 1000 words of Goddess Lalitha, has an end-note that describes what benefits you accrue by chanting these praises to Lalitha. They include cures from disease, prevention of unnatural or early death, wealth, good children, essentially everything that the average person longs for. This same approach defines folk and tribal songs to various gods. The idea is that you sing a song of worship and gain a blessing.

This is reflected in the way elders bless us in India, or the things we ask for during a puja or havan (fire-ritual). The list is rather long but encompasses many of our longings: kshema (safety and security), sthairya (stability or tranquility), veerya (energy, virility), Vijaya (victory), ayur (longevity), arogya (good health), aishwarya (abundance, prosperity), abhi-vridh-yartham (let it increase). The priest also asks for all auspicious things (mangala) for the family and for all the discomforts (duritha) to be pacified.

In Vedic times, the word for the good life was Swasthi. It refers to well-being, and occurs many times in the Vedas: “With Swasthi (well-being), we will go forth.” In fact, the swastika is the symbol for the kind of good life envisaged by our ancestors, hence they drew the design on the walls of their homes.

One idea unique to Indic thought has to do with boundaries, the notion of having enough, which is really about sustainability. So of course you can be ambitious and want to earn money, find pleasure, but the point is that resources are finite and limited and therefore must be shared by family, community and indeed the whole world. And this plays into the adage of “Vasudaiva Kutumbakam,” or the whole world is my family, and therefore desires and ambition must be tempered by moderation because without that sense of restraint, you could want and accumulate without limit. Tempering ambition with moderation—and doing so in a way that sustains all beings creates a blueprint for the good life. With the urgency of climate change, this notion of balance, moderation, restraint, sharing, and embracing the world as your own is arguably the most sustainable way to live.

The problem is that happiness, peace or wealth are not static. They come and go. The meaning of the word Shambhu—which is another name for Shiva—means source of bliss. You could argue that the good life is when you have enough Shambhu in your life to counteract or withstand every calamity. So you do prayers and good deeds in order to accrue this “source of bliss” or Shambhu in your life.

In an excellent lecture, available on YouTube called “Hinduism explained, philosopher Alan Watts talks about how the dharmic life which includes stints in the forest to discover your true self would lead to a point where death itself feels cheated because there would be nothing left to deprive the individual of. As Watts says, “Death comes and will find no one to kill. For while you are identified with your role, with your name, with your ego, there’s someone to kill. But when you’re identified with the whole universe death finds you already annihilated. And there’s no one to kill.”

Cheating death by living the good life is a profound concept.

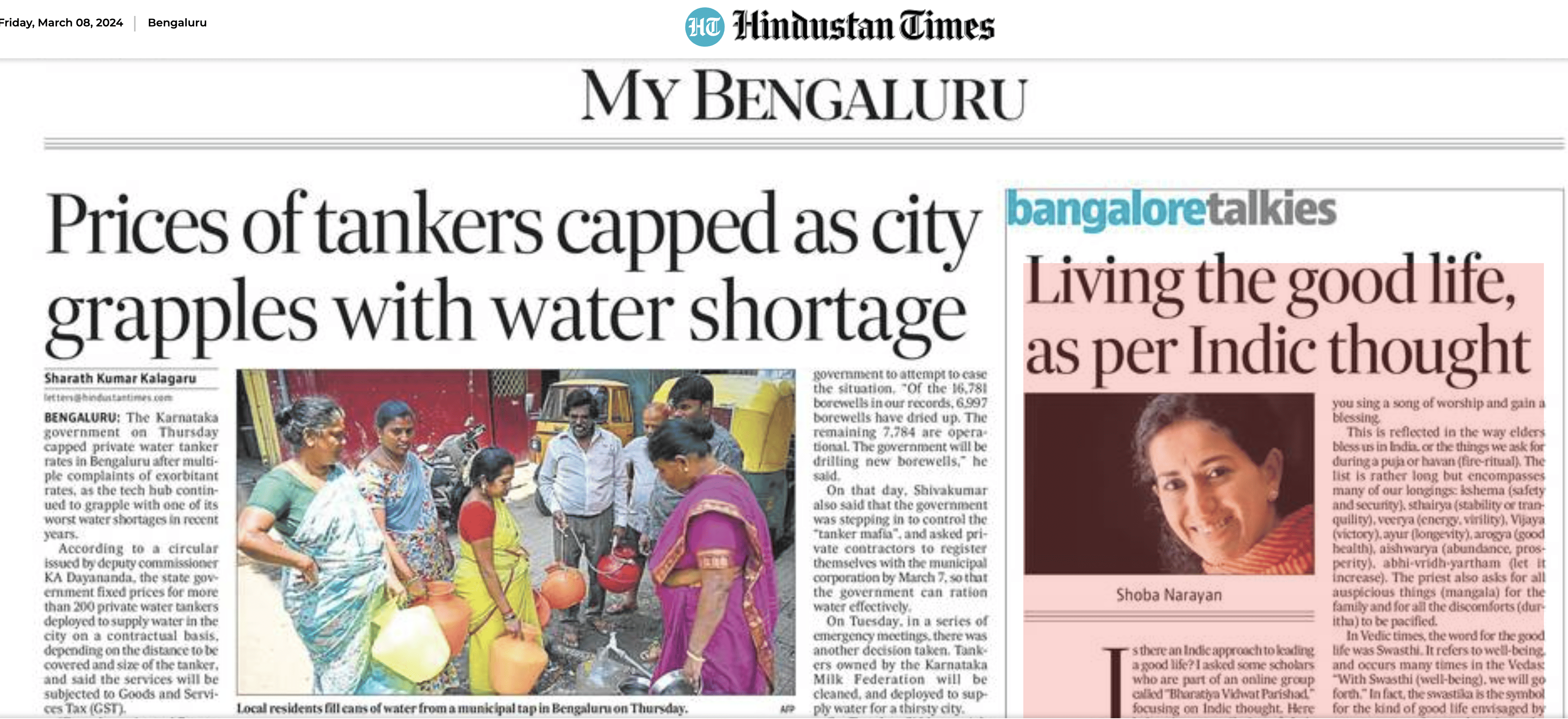

Shoba Narayan is Bangalore-based award-winning author. She is also a freelance contributor who writes about art, food, fashion and travel for a number of publications.

-k4lD-U204025897261YmH-250x250%40HT-Web.jpg)

Leave A Comment