FROM CONDENAST TRAVELER OCTOBER 2006.

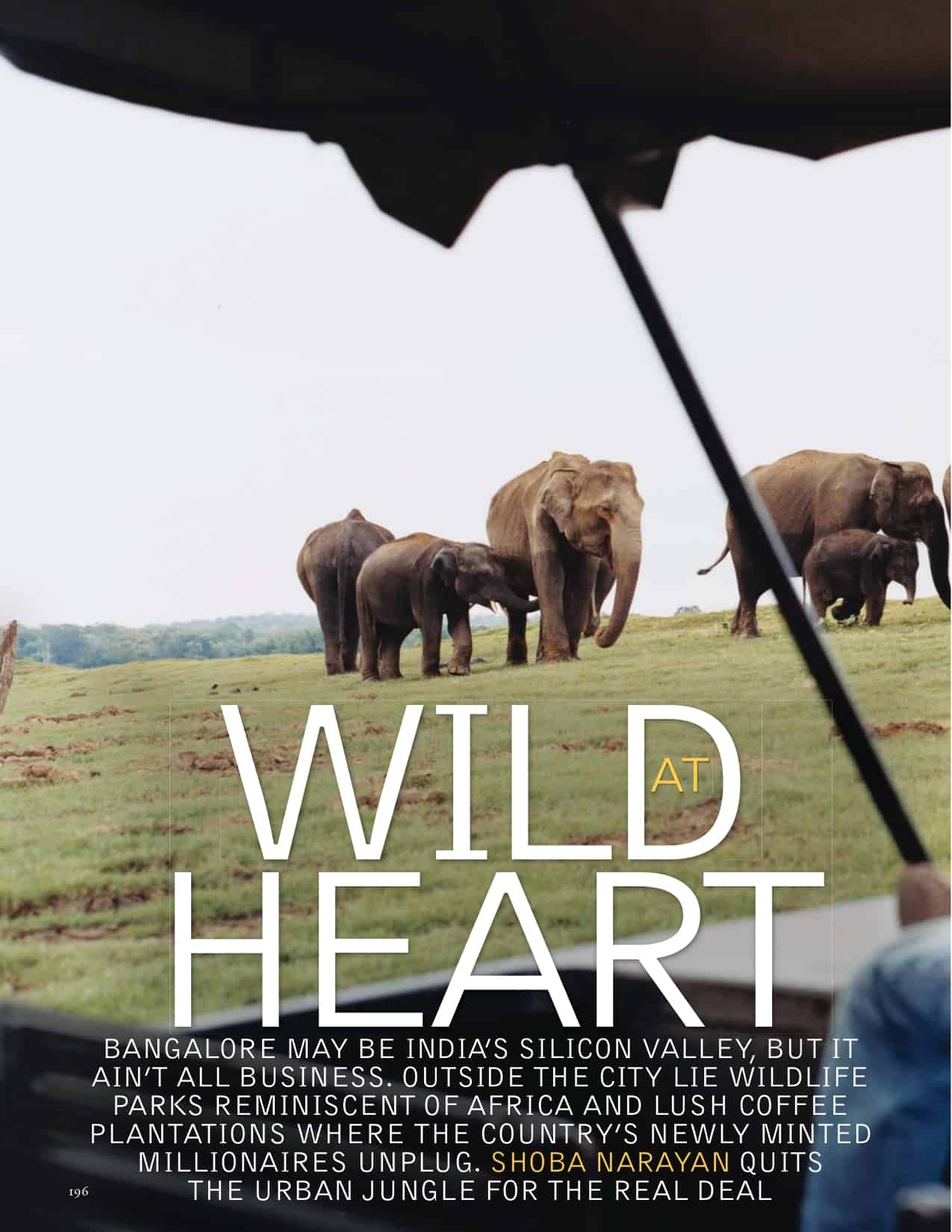

Bangalore may be India’s Silicon Valley, but it ain’t all business. Outside the city lie wildlife parks reminiscent of Africa and lush coffee plantations where the country’s newly minted millionaires unplug.

Shoba Narayan quits the urban jungle for the real deal

Bangalore is home. I didn’t always live here—until two years ago I lived in New York. But now this is the city where my kids go to school, where I hail auto rickshaws for bone-rattling yet perversely exciting rides to work and meetings, where I prowl pubs and malls in search of stories and sales, and where I go to Namdharis Fresh supermarket to buy organic grapes, too-hard bagels, and much-too-soft cream cheese in an attempt to replicate the Sunday morning brunches at my Upper West Side apartment.

Turns out that Bangalore, the capital of the southern state of Karnataka, is also home to some twenty thousand expats who work for Citibank, General Electric, Honeywell, Philips, Texas Instruments, and hundreds of other multinationals. The numbers are small compared with, say, Hong Kong, which has an estimated seventy thousand expats, but foreigners are thronging Bangalore at a rate that is alarming locals. “Are we being Bangalored in Bangalore?” screamed a recent headline, alluding to the growing number of local jobs being taken by foreigners. Eager for international experience, hundreds of freshly minted American MBAs sign on with Indian IT firms. One of them, Nate Linkon, keeps a blog detailing his transition from Milwaukee to Bangalore.

But it isn’t just the techies. Two new Indian airlines, Air Deccan and Kingfisher, are headquartered in Bangalore and are expanding rapidly. With an acute shortage of Indian pilots, they have resorted to hiring Australians, Brits, and Russians, leading to incongruous accents on domestic flights. French and Belgian chefs headline many city hotels. The man overseeing the building of Bangalore’s ambitious new international airport is Swiss. My yoga teacher is from Iran, my daughter’s piano teacher is from Hungary, and one of the reasons I go for a haircut at Talking Headz, on busy Brigade Road, is to get a jolt of stylist Seth Lombardi’s Brooklyn accent.

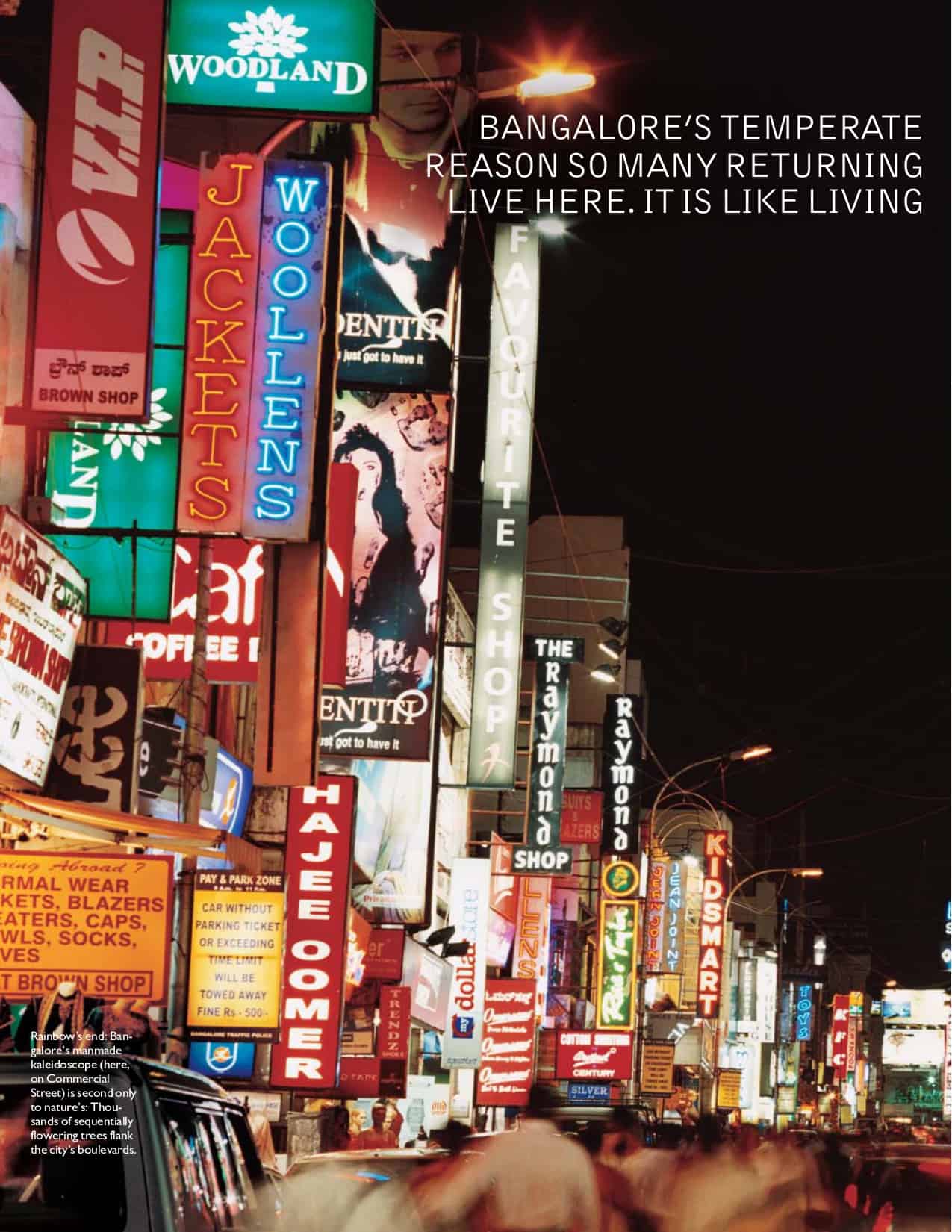

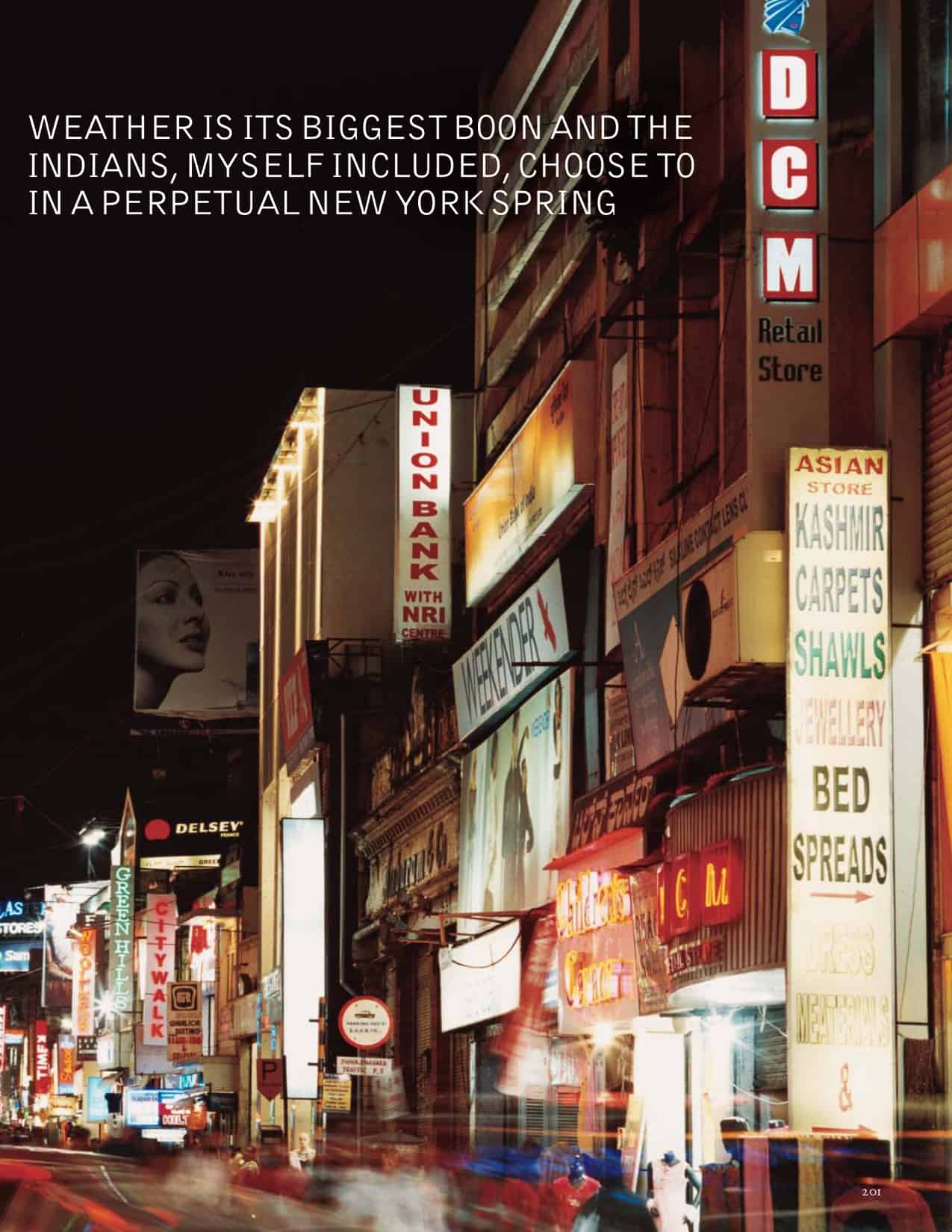

Besides the foreigners who live and work in Bangalore, thousands fly in every day for meetings and conferences or to clinch a deal. They stay at one of the city’s pricey hotels, savor its pubs, buy sandalwood oil and silk scarves, and drive to Electronic City for their meetings. In fact, if you only take in the glass-and-steel high-rises of South Bangalore and ignore the beggars, flower sellers, squeegee men, vegetable vendors, and holy cows, it is possible to imagine that you are driving through California’s Silicon Valley. The banners come quick and bold—Cisco Systems, Google, Hewlett-Packard, Microsoft, Sun Microsystems, Yahoo—and together they give this city its rather uninspired moniker: India’s Silicon Valley.Bangalore is not a valley. It squats atop the Precambrian Deccan Plateau, at approximately three thousand feet above sea level (about the same elevation as Caracas). Winter temperatures rarely drop below the fifties, and even the hottest two months of the year—April and May—see average temperatures only in the high seventies. Bangalore’s temperate weather is its biggest boon and the reason so many returning Indians, myself included, choose to live here. It is like living in a perpetual New York spring, replete with thousands of flowering trees.

Two men—a sultan and a German—were responsible for planting the trees and making Bangalore India’s Garden City. The first, Hyder Ali, who ruled the Deccan Plateau in the eighteenth century, was so taken by Mogul gardens that he resolved to duplicate them. In 1760, Ali set aside 240 acres for the Lalbagh, or Red Garden (named for its roses), and planted trees from all over the world. Emissaries from foreign lands were encouraged to bring plants as gifts. Today, Lalbagh is a thriving park with two-hundred-year-old trees, three-billion-year-old rock formations, dog walkers, joggers, and members of Bangalore’s many laughter clubs—senior citizens who get together every morning just to giggle and guffaw.

It was a German horticulturist who took Hyder Ali’s vision to near-poetic heights. Handpicked by the maharaja to landscape the palace gardens, Gustav Krumbiegel left his stamp all over Bangalore. It was Krumbiegel’s idea to flank the boulevards with sequentially flowering trees: pink tabebuia in January, red bottlebrush in February, purple jacaranda in March, scarlet gulmohar in April and May, brilliant yellow raintree from June through August, golden cassia in September, amherstia in October and November, and fragrant white millingtonia in December.

Like the rest of India, Bangalore contradicts itself all the time. Jobs are so intense that few claim to have the time to read, and yet the city has four newspapers and a magazine called 080 (Bangalore’s area code), and secondhand-book stores abound. The civic infrastructure is under constant threat of collapse, but there are an astonishing number of eco-friendly buildings with solar panels and rainwater harvesters. The roads are potholed, and yet one of them will take you to Soukya, a world-class holistic health center on thirty acres that has attracted the likes of Tina Turner, the Duchess of York, and Archbishop Desmond Tutu. Most youngsters work in fluorescent-lit call centers all night but go hiking, mountain biking, and rock climbing during the day in the craggy terrain surrounding Bangalore.

Come April and May, Bangalore all but closes down: Schools shutter and the city empties out. Earlier this year, I resolved to spend the holiday taking my kids around the region—it was time they got to know their home state. Plotting the itinerary proved half the battle. Karnataka advertises itself as “One State, Many Worlds”—not as catchy as Kerala’s “God’s Own Country” but probably more accurate. As I researched Bangalore’s environs, I discovered many options. To the west are the beaches along the pristine 140-mile Konkan Coast, but they are twelve hours away by car or train and are still developing in terms of tourist facilities. I wanted to visit the twelfth-century temples of Belur and Halebid and the fourteenth-century temple of Hampi (a UNESCO World Heritage Site), but they are far from each other and not conducive to a single itinerary. The only thing we all agreed upon was wildlife. I warned my girls that it would be nothing like the game we saw in Africa a few years back. This is India: There are a billion people and, consequently, a lot fewer animals—and few associate Karnataka with wildlife, probably because Bangalore and its outsourcing success soak up all the attention.The emergence of one company is changing all that. Jungle Lodges & Resorts (JLR) is an offshoot of the government’s tourist department but functions as a private enterprise, which may be the secret to its success. Since its inception in 1980, JLR has set up twelve eco-resorts all over Karnataka and claims to be “the largest ecotourism company in India.” Its operating principle is simple: JLR acquires large tracts of land in remote parts of the state and then nurtures the forest habitat so that the wildlife returns.

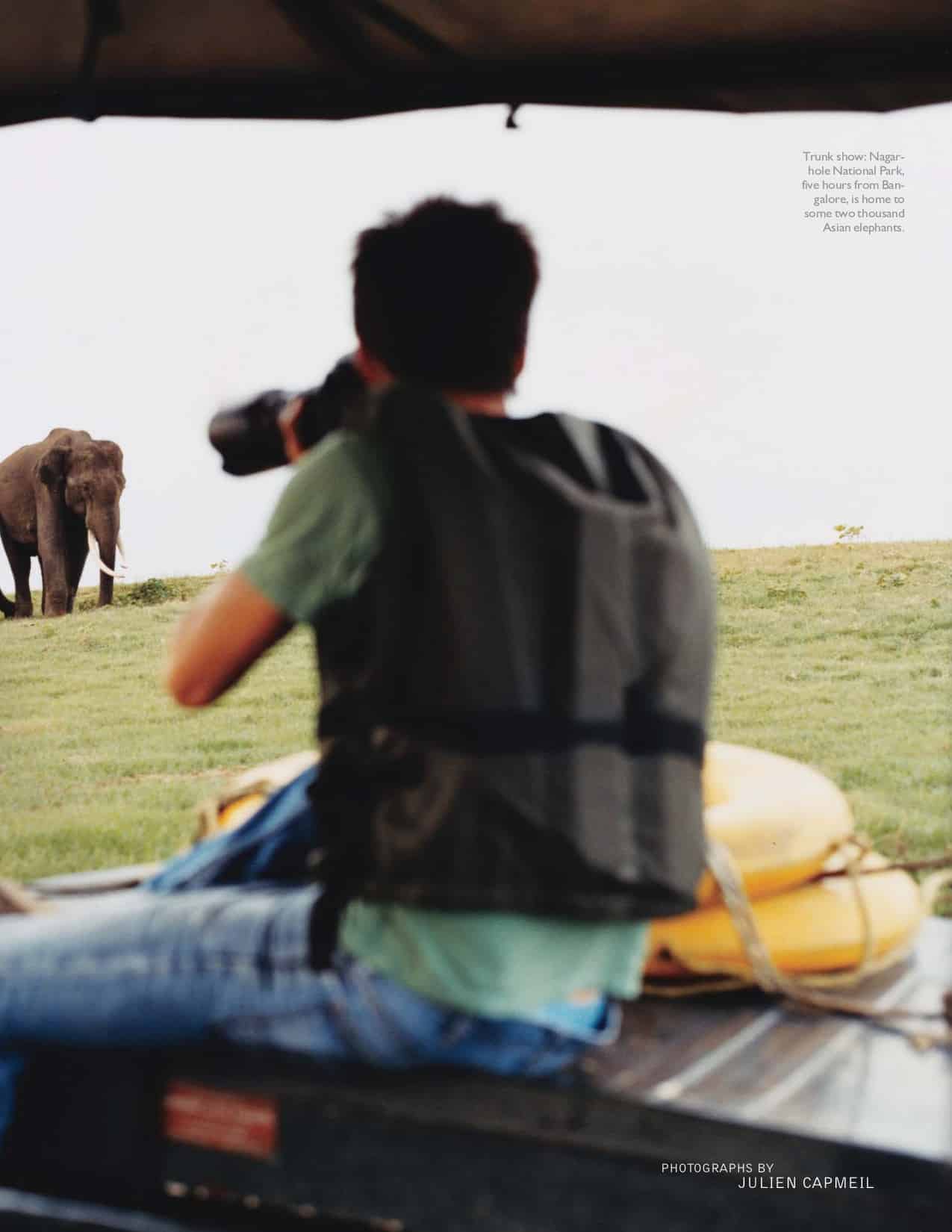

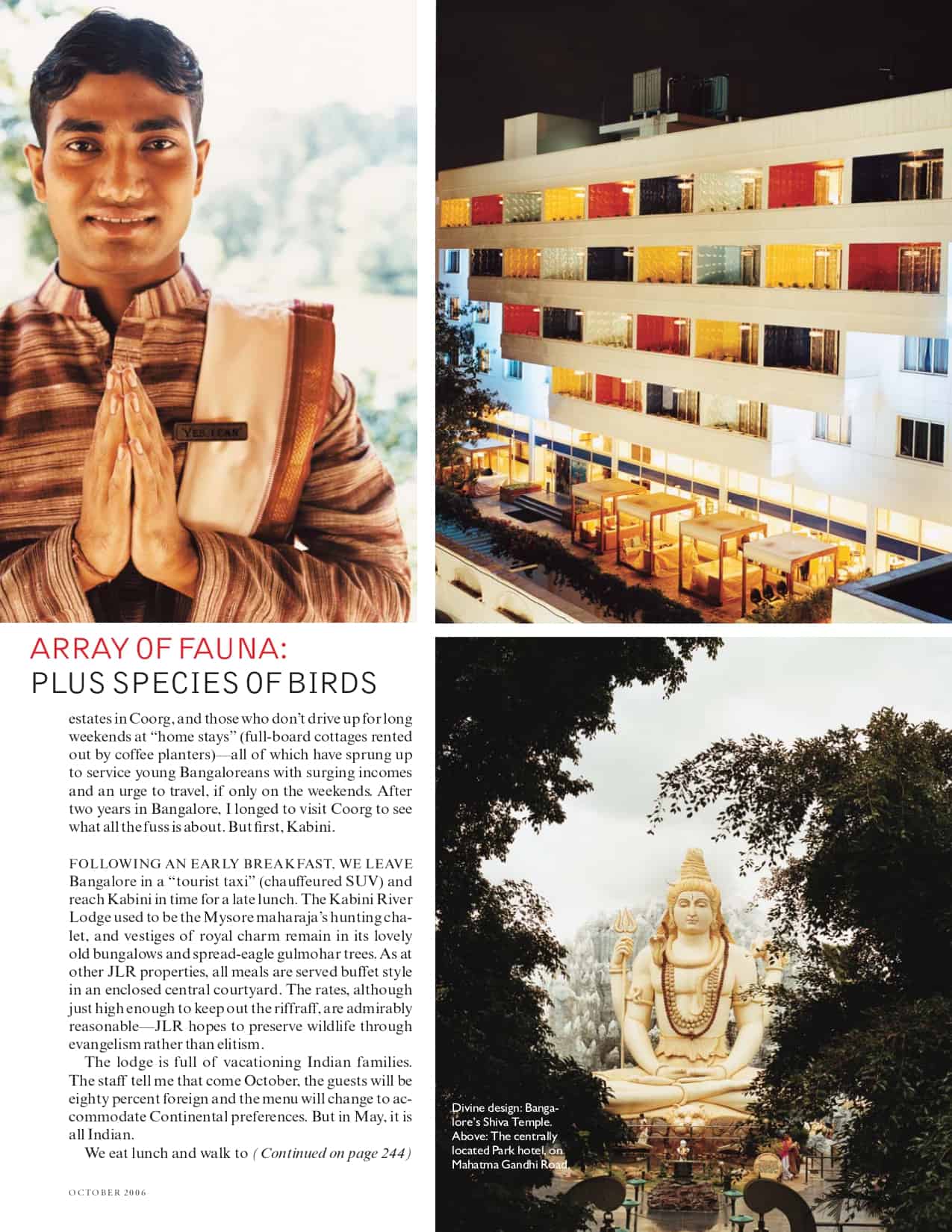

Kabini River Lodge is the company’s flagship. Five hours southwest of Bangalore, it is nestled on the fringes of Nagarhole National Park—which, along with adjoining Bandipur (home to another JLR property), is part of the 1.3 million–acre Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve, which spans three southern states. Nagarhole is home to a spectacular array of fauna: 2,000 Asian elephants, Indian gaur (bison), deer, panthers, leopards, some 50 tigers, and more than 250 species of birds. Tiger enthusiasts prefer the sanctuaries of North India, but if you want to see elephants, then Karnataka and neighboring Kerala are the places to go.

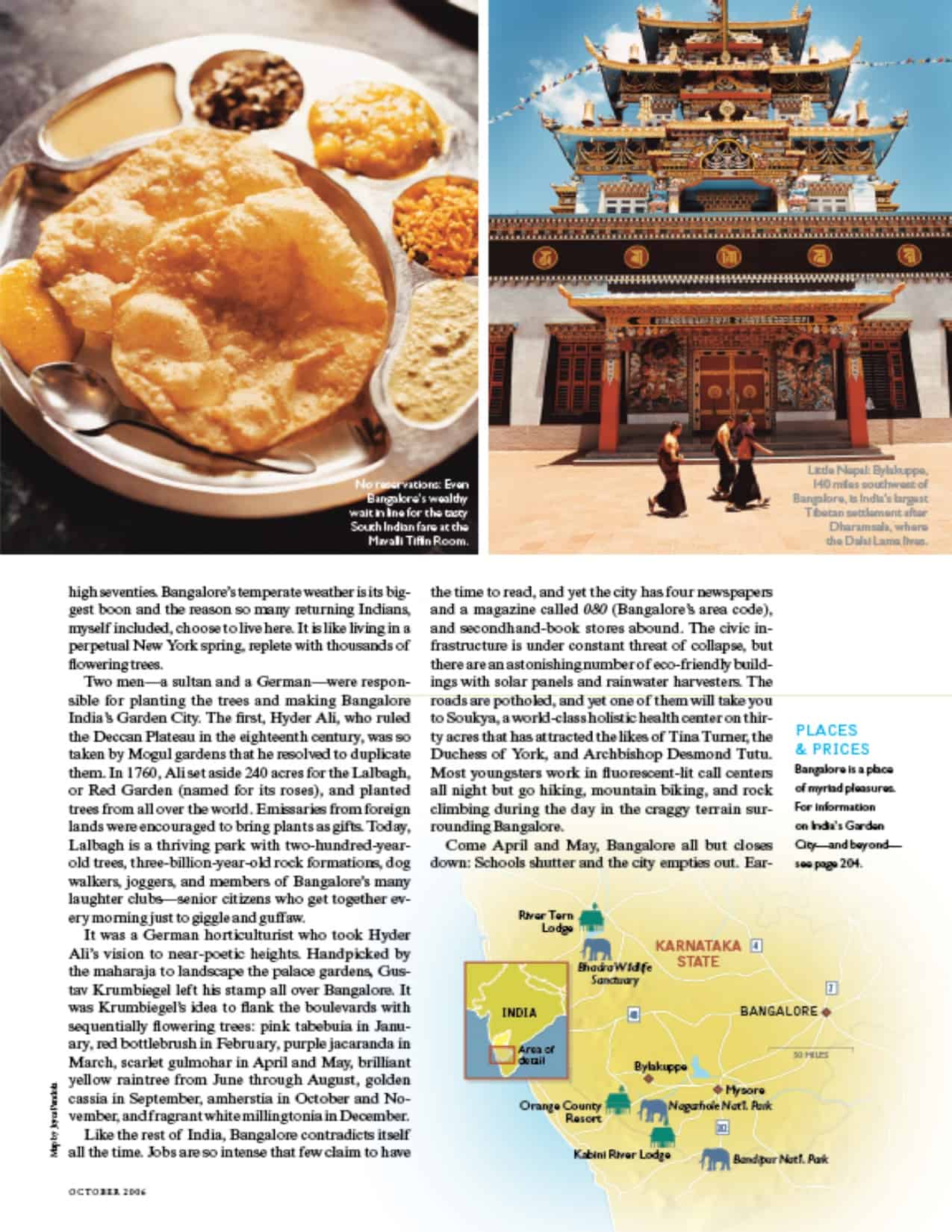

My plan was to spend two days at Kabini, followed by a day in Bandipur and two nights in Coorg, where misty coffee plantations give way to shimmering waterfalls and the second-largest Tibetan settlement in India (after Dharamsala, where the Dalai Lama lives). Coorg is to Bangalore what the Hamptons are to New York City. Most of Bangalore’s boldfaced names have estates in Coorg, and those who don’t drive up for long weekends at “home stays” (full-board cottages rented out by coffee planters)—all of which have sprung up to service young Bangaloreans with surging incomes and an urge to travel, if only on the weekends. After two years in Bangalore, I longed to visit Coorg to see what all the fuss is about. But first, Kabini.

Following an early breakfast, we leave Bangalore in a “tourist taxi” (chauffeured SUV) and reach Kabini in time for a late lunch. The Kabini River Lodge used to be the Mysore maharaja’s hunting chalet, and vestiges of royal charm remain in its lovely old bungalows and spread-eagle gulmohar trees. As at other JLR properties, all meals are served buffet style in an enclosed central courtyard. The rates, although just high enough to keep out the riffraff, are admirably reasonable—JLR hopes to preserve wildlife through evangelism rather than elitism.

The lodge is full of vacationing Indian families. The staff tell me that come October, the guests will be eighty percent foreign and the menu will change to accommodate Continental preferences. But in May, it is all Indian.

We eat lunch and walk to our spacious, comfortable cottage, which has high ceilings and dark wood furniture. Right in front is a tree house surrounded by a giant rope trampoline that looks like a spiderweb on steroids. Watching my kids bounce around on it gives me a beatific sense of satisfaction. They may have access to gizmos galore—iPods, Game Boys, and the like—but give them a ball or a trampoline and they become innocent again. They aren’t jaded, I tell myself. I haven’t messed up.I glare at her. There is no TV, I tell her.

At teatime, the rangers line up in their green camouflage. One of them gives us a pep talk about conservation and Kabini before separating us into teams. I tap my feet, wishing we would get a move on. There’s wildlife to see, tigers to spot.

At 4:30, about ten vehicles speed out of the property and into the jungle along separate trails. Almost immediately, we see herds of chital (spotted) and sambar deer jump across the tracks right in front of us. We hear a peacock cry and then watch a giant male loft itself up toward a distant tree. There are brilliant blue kingfishers, golden-backed woodpeckers, hornbills, hawks, black-and-white hoopoes, and crested eagles. Then we round a bend and come upon our first elephant. The driver brakes hard and turns off the engine. The elephant turns desultorily toward us before continuing to tear down bamboo foliage with its trunk and stuff it into its mouth with rhythmic grace. Some of the people in my jeep bring their palms together and begin praying. To Hindus, the elephant represents Lord Ganesh, the popular elephant-headed god who removes obstacles. Almost every animal in the forest has a connection to a Hindu god: The peacock is Lord Muruga’s vehicle of choice, the fierce goddess Durga rides a tiger, the monkey is venerated as the powerful Hanuman, and snakes adorn Lord Shiva’s neck. Even the humble boar has its place as an avatar of Lord Vishnu. Wildlife conservation in India is happily aided by this Hindu predilection for viewing most animals as gods.

This particular elephant-god isn’t alone. As we watch, another comes out of the bushes, then another, and then, to our delight, a calf. The arrival of the calf seems to make the elders nervous. Swaying their trunks, they amble majestically, as only elephants can, before reentering the forest. We drive on. Langur monkeys with long black tails and white faces swing down from the trees and chatter with one another, occasionally taking a break to remove lice from their young. At first, we stop every time we see them, but soon they become as plentiful as the deer and don’t interest us anymore. The gaur are another matter. Giant beasts with limpid eyes, these buffalo are the vehicle of the god of death in Indian mythology. Lord Yama, we are told, sits atop a buffalo and throws his noose around a dying man before hauling him away. Kabini’s gaur, on the other hand, have no desire to haul humans anywhere. As soon as they spot us, they turn around and disappear into the bushes.

This, then, seems to be the key difference between wildlife sightings in Africa and in India. In Africa, I have watched a lioness with her cubs from twenty feet away; I have sat in a jeep amid a herd of elephants and gotten close enough to touch a giraffe. But here in Kabini, the wild animals are somehow wilder. They are skittish; they run away from humans—as wild animals should.Over the next two days, I see all kinds of creatures: wild boars grunting as they run in packs, hundreds of elephants in distant herds, black-eyed bison peering through foliage thinking they have fooled us because only their curved horns are visible. Hundreds and hundreds of chital and sambar deer. And even a sloth ambling through the bushes. But I don’t see a tiger.

After our last game drive, I am disappointed as we exit the national park. And then, on the road, it happens. We hear a roar and then another. The ranger in our jeep stands up and peers into the bushes with his binoculars. “It’s a tiger,” he whispers. “Right near the road. It is eating its prey.” We all stare at where he is pointing. I think I see some stripes, some movement, but am not sure. Someone says they see two tigers. After a while of squinting into the bushes, we drive on.

Two hours later, we reach Bandipur Safari Lodge. This is a smaller JLR property (only twenty-four guests, compared to Kabini’s fifty) but similarly organized. The staff wake us up at 6 a.m. with hot tea or coffee and biscuits. We gather for a game drive at 6:30 and nap or read in the afternoon before heading out again. By this time, we are veterans. We spot dozens of elephants and even take a ride on one of them, an experience that the kids enjoy but which I don’t, mostly because of the surly mahout. At night, we sit around the campfire and teach our fellow guests “Kumbaya.”

On our last day, we skip the game drive and hike into the forest with a ranger, who warns us about snakes and scorpions. My daughters listen agog to his descriptions of how elephants can climb steep mountains—he shows them elephant dung at the higher elevations as proof. The tribal people who live in the forests have ears and eyes so keen that they can point to tigers moving noiselessly through the bushes, he says.

The Orange County Resort in the Coorg district is a world away from the forests of Bandipur. Spread out over three hundred acres, with the legendary Cauvery River on one side and the fifty-thousand-acre Dubare Reserve Forest on the other, the resort looks like a sprawling planter’s bungalow with tiled roofs and teak beams. Cardamom, cinnamon, and coffee scent the neatly paved paths.

On the trees are tacked mom-and–apple pie maxims that seem strangely out of place amid all the luxury: “Humility usually wins the race of life”; “Keep your mind away from all ego, desires, and attachments.” There are three good restaurants that serve both Western and Indian cuisine, the decor is tasteful, and there are a slew of activities to keep everyone busy. I enjoy reading books in the library and drinking endless cups of cappuccino made with homegrown coffee beans while my kids spend most of their time in the activity center, playing chess and table tennis and making friends.

On our first morning, we take a group hike through the forest with a guide who points out chili bushes, silver oak trees imported from New Zealand, and cardamom and cashew trees, as well as several types of coffee bushes. After an hour’s walk, we reach the Cauvery. Frolicking in a river is an experience that doesn’t come often to us city dwellers, and we enjoy it immensely. My nine-year-old learns from an older boy how to skim a rock over the water; Malu simply dips her feet into the water and squeals every time a fish nibbles at her toes. In India, rivers are viewed as young, tempestuous women, and I can see why. I enter knee-deep water that gushes and gurgles around my feet.The following day, we go to the Dubare Elephant Camp, next door, where for a fee you can give elephants a bath as they loll in the river. I learn that elephants have tough skin and giant rumps. I also learn that an elephant can defecate while you are washing him, and that if you aren’t careful you will be covered with dung-laden water from the ensuing splash—all of which makes me look like an idiot but elicits peals of laughter from my kids. Thankfully, I have brought a change of clothes.

Next, we drive to Bylakuppe to see the Tibetan settlement. When the Dalai Lama took refuge in India in 1959, about a hundred thousand people came with him. In 1974, the Karnataka government allocated two hundred acres of land for these Tibetan refugees, and thus began the second-largest settlement in India. Today, Bylakuppe has a thriving Tibetan monastery with some five thousand resident monks, many of them sponsored by American Buddhists. Busloads of tourists come, especially on weekends, to see the Namdroling Monastery. Inside is a temple containing three giant golden statues that look down benevolently on the devotees. Prayer flags flutter, Tibetan women sell beads, young monks run around in sandals, and the grizzled ones sit in a corner drinking butter tea. One of them fans himself furiously. I smile. They have traded the Himalayas for the heat, but they seem happy. What an odd place, I think—a slice of Tibet in interior Karnataka.

Soon it is time to return to Bangalore. My girls exchange e-mail addresses with their newfound friends and promise to keep in touch. We buy a packet of Siddapur coffee in the gift shop before checking out.

As we drive back, I wonder what it is about nature that so inspires us. Spotting wildlife, no matter where, is a startling experience; it raises the hair on the back of our necks, makes us go still. Of course, one reason is that the animals are so rare, but I also believe that seeing them touches a primitive part of us that layers of evolution have covered up. In wildlife, we see the part of ourselves we’ve left behind; the part that is freer and more formidable but also—in today’s world—more vulnerable.

It is late afternoon when we reach Bangalore. Traffic is at a standstill, horns honk, and there is concrete as far as the eye can see. I miss the verdant green of Kabini, the cool waters of the Cauvery, and the unpolluted air of Coorg. I miss the majestic elephants, the elusive tiger, and the inquiring gaze of the langurs. At a stoplight, we rear-end the car in front of us. A furious man gets out, and I steel myself for yet another wildlife encounter—the bipedal kind.

Places & Prices

Bangalore is temperate throughout the year. It is also a progressive city, so women can wear anything, including halter tops. Orient yourself by taking one of the witty and knowledgeable three-hour city tours offered by BangaloreWalks (98455-23660; bangalorewalks.com; $11 per person). It is safe to hire taxis and auto rickshaws in Bangalore; the drivers are honest and use a meter to record the fare.

The country code for India is 91. A visa is required. Prices quoted are for October 2006.

Lodging

The opulent Leela Palace is arguably the city’s best hotel (80-2521-1234; theleela.com; doubles, $450–$620). The leafy, white Taj West End, which opened more than a century ago, reflects Bangalore’s British colonial past and has the wonderful assurance of a grande dame (80-5660-5660; tajhotels.com; doubles, $420–$425). Well-situated on Mahatma Gandhi Road—MG Road to locals—are the sprawling yet serene Oberoi (80-2558-5858; oberoihotels.com; doubles, $400–$475); the edgy, design-conscious Park Bangalore (80-2559-4666; theparkhotels.com; doubles, $350); and the businesslike Taj Residency (80-6660-4444; tajhotels.com; doubles, $290–$400). The Grand Ashok—a favorite of politicians and dignitaries—is across from a golf course and has a spanking-new spa (80-3052-7777; bharathotels.com; doubles, $325–$400).

Jungle Lodges & Resorts operates all of the wildlife retreats mentioned in the article, and can arrange transportation to and from the city (80-2559-7021; junglelodges.com; doubles, $80–$240). Orange County is the largest resort in Coorg (80-2558-2380; trailsindia.com; doubles, $183–$300), though home stays in rustic but comfortable bungalows are available at a fraction of the price (see “Reading” for where to find them).

Dining

I-talia, at the Park Bangalore, serves genuinely fine Italian food (14/7 MG Rd.; 80-2559-4666; entrées, $10–$13). The Legend of Sikander does fantastic kebabs in a vaguely Egyptian setting (Garuda Mall, 4th fl.; 80-5125-2333; entrées, $3–$6). Mainland China serves Indian-Chinese fusion cuisine to a packed house (14 Church St.; 80-2559-7722; entrées, $3–$7). The Mavalli Tiffin Room doesn’t take reservations, so you’ll have to queue up for the rich, tasty South Indian food (14 Lalbagh Rd.; 80-2222-0022; entrées, $2–$3). Olive Beach, an outpost of Mumbai’s acclaimed Olive, is set in a lovely Moorish bungalow. The kitchen is still finding its feet but has a lovely meze and a delicious lobster risotto (16 Wood St.; 80-4112-8400; entrées, $7–$19). Rim Naam, at The Oberoi, has great Thai food, including stir-fried squid with cashews and lemongrass (39 MG Rd.; 80-2558-5858; entrées, $10–$18). Sunny’s, a local institution, makes superb salads and thin-crust pizzas (34 Vittal Mallya Rd.; 80-4132-9366; salads and pizzas from $4). Citrus, at the Leela Palace, has the best Sunday brunch in town. Book way in advance (23 Airport Rd.; 80-2521-1234; buffet brunch, $17).

The Daily Bread chain makes excellent bread, muffins, and pastries; the one near Ulsoor Lake is particularly good (Forum Mall, inside the Fabmall outlet).

When you pass through Mysore en route to Kabini or Coorg, have lunch at the opulent Lalitha Mahal Palace hotel, just below Chamundi Hill (821-247-0470; entrées, $5–$11).

Spas

Decleor does one of the best facials in town (32 Cuningham Rd.; 80-2235-5881; facials from $25). Rejuve, at the Grand Ashok, has a color therapist who aims to balance your energy using colors, prisms, and gemstones (80-3052-7777; color therapy from $120). Soukya, an hour from Bangalore, has half- and full-day packages that include a hot-stone massage and lunch (Soukya Rd., Whitfield; 80-253-18405; soukya.com; half-day, $40). The Spa at the Leela Palace is a great place to get your eyebrows “threaded” into shape—the preferred method among Indian women (80-2521-1234; eyebrows threaded, $4). Dr. Bhanu Moorthy, of Prithvi Natural Healing & Yoga, will provide private yoga instruction in your hotel room (80-4116-1666; $50 per hour).

Shopping

Government-owned Cauvery Arts & Crafts is a one-stop shop for souvenirs from sandalwood idols to incense to handicrafts (45 MG Rd.). Nearby, PN Rao Tailors has been in business for generations and can deliver a bespoke suit in 24 to 48 hours (69 MG Rd.). The Vintage Shop has lovely curios and will ship purchases abroad (15 Rustum Bagh Main Rd.). Crossword (Bannerghatta Rd.) and Gangarams (72 MG Rd.) are good bookstores in the center of town.

Reading

For an up-to-date listing of events and shops, pick up a free Explocity guide in your hotel (explocity.com). Bangalore & Karnataka (Stark World, $16) and the Food Lover’s Guide to Bangalore (Taste & Travel, $2) are also good and are available at any city bookstore. Weekend Breaks from Bangalore has a list of home stays (Outlook Traveller, $5).

Leave A Comment