About the Hermes Sari. Appearing here in the Financial Times Weekend fashion pages and pasted below.

January 13, 2012 10:05 pm

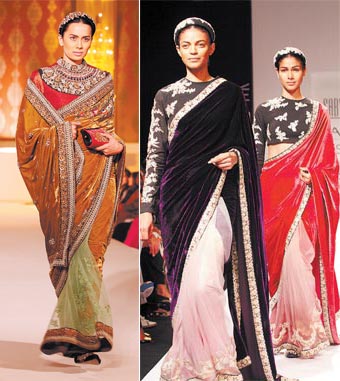

Saris from Paris?

By Shoba Narayan

At his flagship Calcutta store, fashion designer Sabyasachi Mukherjee is extolling the glories of his new Kanjivaram collection to an adoring clientele. He pulls out silk brocade saris and points out complex weaves and disappearing flower motifs, raving about the nine exclusive weavers he employs in the ancient silk weaving centre of Kanjivaram, in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu.

Then a slim twentysomething woman walks in, dressed in a short Gucci dress, with Fendi sandals, Bulgari sunglasses and Prada bag. Her sari-clad mother wants to buy her a Kanjivaram sari, priced at about £1,800. The daughter refuses, saying that the “heavy silk weaves” will make her look fat. She prefers Mukherjee’s transparent “net saris”.

“Indians are moving away from our handmade textile traditions,” Mukherjee says, mournfully. “This is why a brand like Hermès has the audacity to come in here and sell a printed sari for £5,500. The sad thing is that Indians will queue up to buy those Hermès saris but they will ignore our handcrafted weaves.”

Indeed, the launch in India of 28 limited-edition Hermès styles only two months ago has ignited an intense debate, with factions (traditional and non) facing off against one another. At issue: the fact that a French brand is selling a simple “bazaar-type sari”.

“I was so angry when I saw it,” says designer Deepika Govind, who specialises in organic, eco-friendly fabrics. “It is obnoxious to come and wave a simple printed sari in our faces and say, ‘We’ve done a sari.’ OK, but show us something we haven’t done.”

Like Mukherjee, Govind speaks reverentially about difficult weaves such as the Patan patola (a reversible weave that appears luminous on both sides); the Bagh prints of Madhya Pradesh (intricate handblocked floral prints coloured with vegetable dyes); and the geometric, multilayered ajrakprints of Rajasthan. “We are sitting on a gold mine,” she says. “If a company can take a very basic design and release it worldwide for that outrageous price, it just shows that we don’t know how to market our products. If any fool were to buy this [Hermès] sari, if any Indian were to buy it! I cannot see a reason to own this product.”

Hermès, however, says that selling a sari in India is not taking coals to Newcastle. Rather, it wants to “connect with Indian tradition and elegance,” says Bertrand Michaud, president of Hermès India. And there is precedent, thanks to Hermès’ Marwari scarves (prints inspired by the rare horses of Jodhpur) and sari-dresses designed by Jean Paul Gaultier in spring 2008 when he was creative director of the brand. Those, however, were riffs; this is a more significant collection. “It is like Indians selling wine in France,” sniffs one Indian style expert. “To sell a sari in India takes Gallic gall.”

Michaud prefers to call it homage. “The idea of the saris was to honour Indian culture and offer an Hermès interpretation of this traditional garment,” he says. Indeed, the brand’s entry into India follows its successful Shang Xia brand in China, which blends home-grown products with Hermès sensibilities.

‘It is like Indians selling wine in France. To sell a sari in India takes Gallic gall,’ says one Indian style expert

Hermès is just one of the many luxury brands thronging the Indian retail space, drawn by the fact that the Indian luxury market, which was a mere $4.76bn in 2009, is expected to grow by 20-25 per cent annually to reach $14.7bn by 2015, according to a report from the Confederation of Indian Industry.

Mayank Mansingh Kaul, a textile designer who has worked with the Indian government on policy related to handicrafts, says: “A lot of Indian designers are critical of the Hermès sari but we have to focus instead on promoting the use of saris among the younger generation – and for more occasions than weddings and festivals.”

Saris have a complicated history in India, dating back to the Indus Valley civilisation. Had Hermès launched a range of dupattas or stoles, or any other garment, the brand would not have provoked so much emotion and ire. But saris, as Rta Kapur Chishti says in her book Saris of India: Tradition and Beyond, are part of the Indian identity and represent a culture in which the woven and unstitched garment was considered not just climatically appropriate but also “an act of greater purity and simplicity”.

Still, not everyone is so critical of Hermès. Handloom researcher Uzra Bilgrami points out that for all their criticism of Hermès, Indian designers themselves don’t wear saris, choosing instead to “run around” in blue jeans. Bandana Tewari, fashion features director of Vogue India, who calls herself a big supporter of Indian handicrafts, says: “The Hermès sari is a nice modern print; completely anti-bling. It isn’t over the top or trying to compete with the textile artisans based in Rajasthan. Hermès is just doing what comes naturally to them,” – ie printed silk. However, though sometimes a sari is just a sari, it can also be a political hot potato.

nice article! you should write a story about people in India who buy this sari eventually and their reasons for it! I am curious for one…

Good idea, V. Thanks.

OMG, been here yet?

http://sarangithestore.com/

Yup!!