In anticipation of her daughter’s wedding, Shoba Narayan set out to hone her mehndhi craft

The old crone pulled me closer. I was 25, shy, and about to have an arranged marriage with a Wall Street banker. Both of us had studied in the United States, met a couple of times, but hadn’t dated in the Western sense of the term. A few days before the wedding, two Rajasthani women came to my home to apply mehndi for my 25 cousins and me. By Indian standards, we were a small family.

“What is his name?” asked my henna-lady. “The man you are going to marry.”

Ram. His name was Ram.

She frowned. She needed a longer name. She was going to hide the letters within the floral patterns on my palm.

I knew the tradition, common in North India. After the wedding rituals, surrounded by cackling relatives, the bridegroom would hold the bride’s hand and search for his name in the mehndi patterns of her palm. It was a great icebreaker, particularly in traditional marriages where the couple was seeing each other for the first time at the ceremony.

My henna-lady bent her head and began inserting the letters of my fiancée’s last name—Narayan—within the watery, wave-like lines and floral trellises that she had drawn. She wrote the letters in Hindi. They disappeared into my palms like a mirage, even as she drew them. How was my husband going to find them on our first night together?

“He won’t let go of your hand on your wedding night,” she said with a wicked smile.

That he didn’t; and hasn’t for the last 23 years that we’ve been married. Corny, I know, but hey, just in case you were wondering.

Like most Indians, I grew up with hovering grandmothers, bubbling kitchen aromas, and a henna plant in our backyard. Called mendhika in Sanskrit, marudhani in Tamil, mehndi in Hindi, and henna from the Arabic al-hinna, the flowering shrub lawsonia inermis has multiple uses, many of them involving hair. India’s indigenous medical traditions like Ayurveda and Siddha, which rarely agree upon anything, all state that henna is good for hair. It prevents dandruff, graying, hair loss, and verily old age. Indian women infuse its leaves into the coconut oil that they massage into the scalp.

Henna is also marketed as an herbal hair dye. The process is elaborate. Henna powder is mixed with brewed tea, lemon juice, and coconut oil, and left overnight in a cast-iron pot before applying it to a woman’s flowing locks, or a horse’s mane for that matter, which is what nomadic tribes used to do. In South India, we pick fragrant white henna flowers by moonlight and put them underneath our pillow for a good night’s sleep.

Henna’s greatest use however, is for adornment, a purpose it has served at least since the 4th century, when a scholar named Vatsyayana wrote the Kama Sutra. In the text, Vatsyayana outlines the various arts that a woman needs to learn in order to please and seduce. Applying mehndi on palms, shoulders, and the back, is one of them. (Breasts get designs too, but made with saffron and musk. Nearly two millennia later, Indian women continue the practice—mainly for special occasions like weddings and festivals. For visitors to India, getting a mehndi is a unique cultural experience that you can take home with you: the dye may fade, but the memory will remain.

India, Egypt, and Persia all lay claim to the origin of henna designs. Early Egyptians dipped their palms into henna paste and discovered that it cooled down their body. Indians used to draw a simple circle on their palms and cap their fingers with henna paste. South Indian women still use these traditional designs: a large circle on the palm surrounded by smaller circles, with capped fingers. For the most part however, henna designs have evolved into an elaborate art.

“Henna designs begin with common Indian motifs like the bhel or creeper-vine, mor or peacock, mango or paisley, lotus and other flowers,” says Durga Singh Mandawa, a folklorist and tour guide who has converted his family property in Jaipur into a boutique hotel called Dera Mandawa.

I am in Jaipur to get a mehndi lesson. My elder daughter has left for Carnegie Mellon University in Pennsylvania to get an undergraduate education. Like any good mother, I want to prepare for her wedding, and yes, she rolls her eyes every time I say this, which really is the point of saying it. While she is taking programming classes at CMU, I dream of painting her hands with elaborate henna designs as part of what is known in Indian aesthetics as solah shringaa. Indian aesthetics calls ‘solah shringaar,’ or the ‘16 adornments’ of the bride. I’m not content just to hire an expert. I want to adorn my daughter with my own hand.

Rajasthan boasts the mother lode of henna artists in India, but even in Bangalore, where I live, there are dozens to be found in the yellow pages. Before trekking to Jaipur, I get some recommendations from friends and meet five henna-ladies to get an initial private lesson. They all speak Hindi, except for Saba Noor, 21, who speaks fluent English. Noor works at a Bangalore start-up, does henna on the side, and is taking MBA classes at night. “Can you draw?” she asks before even agreeing to see me.

Over her lunch break, she starts to unpack the mysteries of henna for me.

“There are three trends,” she says. “The Arabic design is linear with big flowers. Lots of empty spaces. Indian design has Radha-Krishna, peacocks and floral motifs. Indo-Arabic fusion has geometric triangles along with flowers.”

So begins the education of Shoba—potential henna-artist extraordinaire.

Noor shows me designs and patterns that I must endlessly repeat on paper with a black pen—not pencil. Henna is unforgiving and doesn’t allow for mistakes, so it’s important to practice without an eraser. The paisley-peacock-floral motifs, familiar to generations of Indians, are repeated not just in henna but also in India’s woven saris, block-printed textiles, carved wood furniture, stone sculptures in temples, wall frescoes, and the rangoli-patterns that adorn courtyards.

All designs start with a circle; then you draw petals around the circle, fill in the petals with straight lines, and go from there. After a few weeks of practice, you make a paste with atta or wheat flour that is about the consistency of cake icing. The flour paste will not stain so the novice can now experiment with impunity. Noor, my first teacher, is a purist and makes her own mehndi-cones with plastic. Most others buy them readymade.

Over several days, I practice drawing floral vines across my palms and geometric “bangles” around my wrist using flour paste. They smudge. They’re not uniform. They’re disproportionate. Still, I can see myself getting better.

“Don’t worry,” says Noor kindly. “True henna artists have three things in common: patience, persistence, and an eye for proportion.”

She encourages me to go to Rajasthan, where it all began.

Some of the best henna comes from Sojat town in Pali District, Rajasthan. Here, the henna shrub spreads as far as the eye can see. Women in Rajasthan apply mehndi throughout the year: for festivals such as Dussehra, Diwali, Teej, and Karva Chauth, and for family weddings.

“Professional mehndi women were an oxymoron in Rajasthan until about 15 years ago,” says Mandawa over a meal of aloo paratha (potato flatbread), dal, and okra curry. “Until recently, women used to apply mehndi on each other’s hands, singing folk songs.”

He sings a popular ballad, “Bhanwar puncho chodo hatha me rach rahi mehndi.”

“Oh my beloved. Leave my wrist.

You will smudge my mehndi.

You yourself got the mehndi

It is for you that I adorn my hands.”

Another folk song talks about the choicest mehndi that has been brought from the Malwa Plateau “very lovingly for this beautiful girl who everyone dotes on,” and then lists all the relatives—uncles, aunts, grandfather, grandmother, cousins, and brothers—who brought the bride the orange paste that will stain her fingers.

Traditional Rajasthani families disdain henna leaves. Instead they harvest the fruit in season, and store it in a box for use through the year. They take out small quantities when needed, mashing and mixing it with a mortar and pestle.

“In Sojat, machines harvest mehndi—taking in fruits, leaves, bark and stem,” says Mandawa, curling his mustache with a frown.

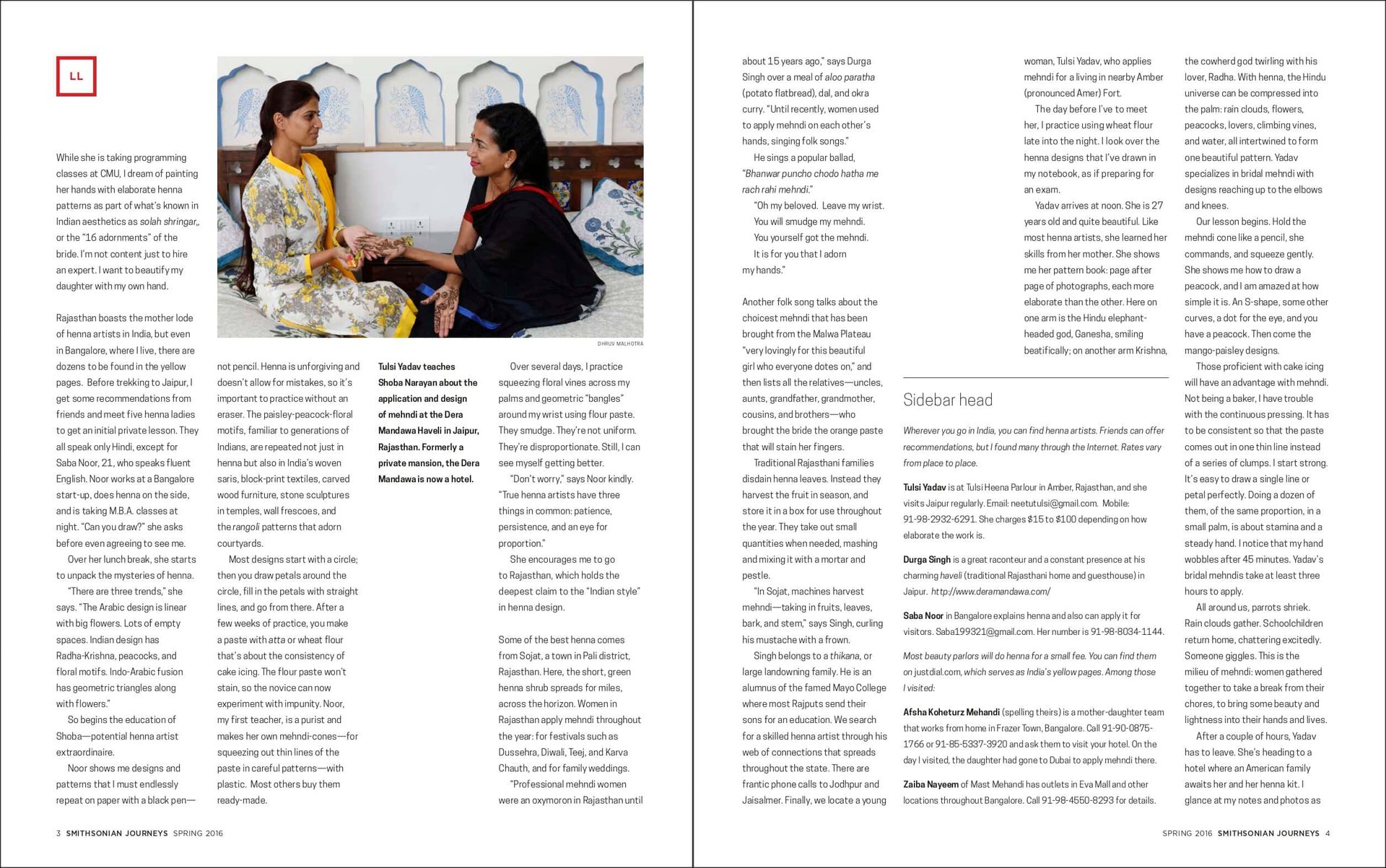

Mandawa belongs to a “thikana” or large landowning family. He is an alumnus of the famed Mayo College where most Rajputs send their sons for an education. We search for a skilled henna artist through his web of connections that spreads throughout the state. There are frantic phone calls to Jodhpur and Jaisalmer. Finally, we locate a young woman, Tulsi Yadav, who applies mehndi for a living in nearby Amber (pronounced Amer) fort.

The day before I am to meet her, I practice using wheat flour late into the night. I look over the henna designs that I have drawn in my notebook, as if preparing for an exam.

Yadav arrives at noon. She is 27 years old and quite beautiful. Like most henna artists, she learned her skills from her mother. She shows me her pattern-book: page after page of photographs, each more elaborate than the other. There on one arm is the Hindu elephant-headed god, Ganesha, smiling beatifically; on another arm Krishna, the cowherd god twirling with his lover, Radha. With henna, the Hindu universe can be compressed into the palm: rain clouds, flowers, peacocks, lovers, climbing vines, and water, all intertwined to form one beautiful pattern. Yadav specializes in bridal mehndi with designs reaching up to the elbows and knees.

Our lesson begins. Hold the mehndi cone like a pencil, she commands, and squeeze gently. She shows me how to draw a peacock and I am amazed at how simple it is. An S-shape, some other curves, a dot for the eye and you have a peacock. Then come the mango-paisley designs.

Those proficient with cake icing will have an advantage with mehndi. Not being a baker, I have trouble with the continuous pressing. It has to be consistent so that the paste comes out in one thin line instead of a series of clumps. I start strong. It is easy to draw a single line or petal perfectly. Doing a dozen of them, of the same proportion, in a small palm, is about stamina and a steady hand. I notice that my hand wobbles after 45 minutes. Yadav’s bridal mehndis take at least three hours to apply.

All around us, parrots shriek. Rain clouds gather. School children return home, chattering excitedly. Someone giggles. This is the milieu of mehndi: women gathered together to take a break from their chores, to bring some beauty and lightness into their hands and lives.

After a couple of hours, Yadav has to leave. She is heading to a hotel where an American family awaits her and her henna kit. I glance at my notes and photos as she walks out. “Practice,” she says encouragingly. “Don’t give up. It will get easier.”

After Yadav departs, all I can do is loll around in bed. Covered with henna designs that need to set, my hands are useless. I dab a solution of sugar water and lemon juice periodically over the mehndi to deepen its color. After a half hour, I rub my hands together over a rose bush. Dry green henna flakes fall like pixie dust over the plant.

Women do many things to deepen henna’s orange color. They apply eucalyptus, or any other oil; sleep overnight with the henna wrapped in plastic gloves; and don’t wash with water once it is removed. The average henna “tattoo” lasts about three weeks. If you are constitutionally what Ayurveda calls ‘pitta’ or “high in heat,” denoted by a ruddy face, prone to red rashes, and early balding, the color is darker—like dark chocolate. Mine is the color of Bordeaux wine.

That evening, I go to Bapu Bazaar in downtown Jaipur. At the entrance, a line of migrant men from different parts of Rajasthan sit on makeshift stools, drawing henna designs on passersby for a small fee. I chat with one young man named Rajesh. He learned the art from his brother, he says. He glances at my hands quizzically. “Why one hand good and the other hand bad?” he asks.

“This hand, teacher did. This hand, I did,” I reply, imitating his English.

He smiles. “Don’t give up. It took me six months to get perfect,” he says.

Henna is a child of leisure, or in the case of Indian women, the mother of leisure. It engenders relaxation. It gives them time and space to pause, removing them briefly from the responsibility of running homes. It also turns them into gossipy, giggling youngsters.

Two college girls sit across from Rajesh and put out their palms. With lightning hands, he draws the designs I’ve become familiar with: petals and peacocks, Radha and Krishna. The girls chat and chortle as a tapestry of tradition is painted on their hands. It reminds them of home perhaps, just as it does for Indians of the diaspora in Chicago and Queens, who get orange patterns drawn on their palms during holidays.

I glance at the peacock on my palm that Yadav executed with quicksilver strokes. It seems to be winking at me. I watch the henna artists all around, fiercely concentrating on the outstretched hand in front of them. Will I get that good? I have a few years. My daughter is just a sophomore, swimming in advanced calculus and thermodynamics classes. She doesn’t know my “secret plans and clever tricks,” to quote Roald Dahl. I will get better. Tradition is a transmission, involving delivery, handing over, and for the student, surrender along with practice. With mehndi, I am reaching back into the mists of India’s hoary history to grab what is tangible and beautiful to shrink into the palm of my hand.

Sidebar:

Wherever you go in India, you can find henna artists. Friends can offer recommendations, but I found most of my henna artists through the Internet. Rates vary from place to place.

Tulsi Yadav is at “Tulsi Heena Parlour.” Website: www.tulsiheenaparlour.com. Email: [email protected]. Mobile: 91-9829326291. She charges $15-100 depending on how elaborate the work is.

Durga Singh Mandawa is a great raconteur and a constant presence at his charming haveli (traditional Rajasthani home). http://www.deramandawa.com/

Saba Noor explains henna and also do it for visitors. [email protected]. Her number is +91 98-80-341144

Most beauty parlors will do henna for a small fee. You can find them on justdial.com, India’s yellow pages. I visited several.

Afsha Kohetur Mehandi (spelling theirs) is a mother-daughter team that operates from their home in Frazer Town, Bangalore. Call +(91)-9008751766 or +91-8553373920 and ask them to come to your hotel, which they will. On the day I visited, the daughter had gone to Dubai to apply Mehndi.

Zaiba Nayeem of Mast Mehandi has outlets in Eva Mall and other locations throughout Bangalore. Call +91 98-45-508293 for details.

Walk down Commercial Street, Bangalore’s shopping thoroughfare and you will spot beauty parlours with hennaed hands on the signboards. If you want a flavor of mehndi, just duck in.

Leave A Comment