“Here,” said my mother, pressing a dark-brown slab of one of her mysterious cooking ingredients into my hands. “Smell this.”

I was nine. I obeyed.

“It smells stinky,” I said, wrinkling my nose as I turned over the hard, pockmarked resin in my palm. “Like a…,” I giggled, unable to say the rude word.

My mother smiled, as if I had understood some fundamental cooking concept. “It’s asafetida,” she said. “You sprinkle it on foods like beans and lentils so they won’t give you gas.”

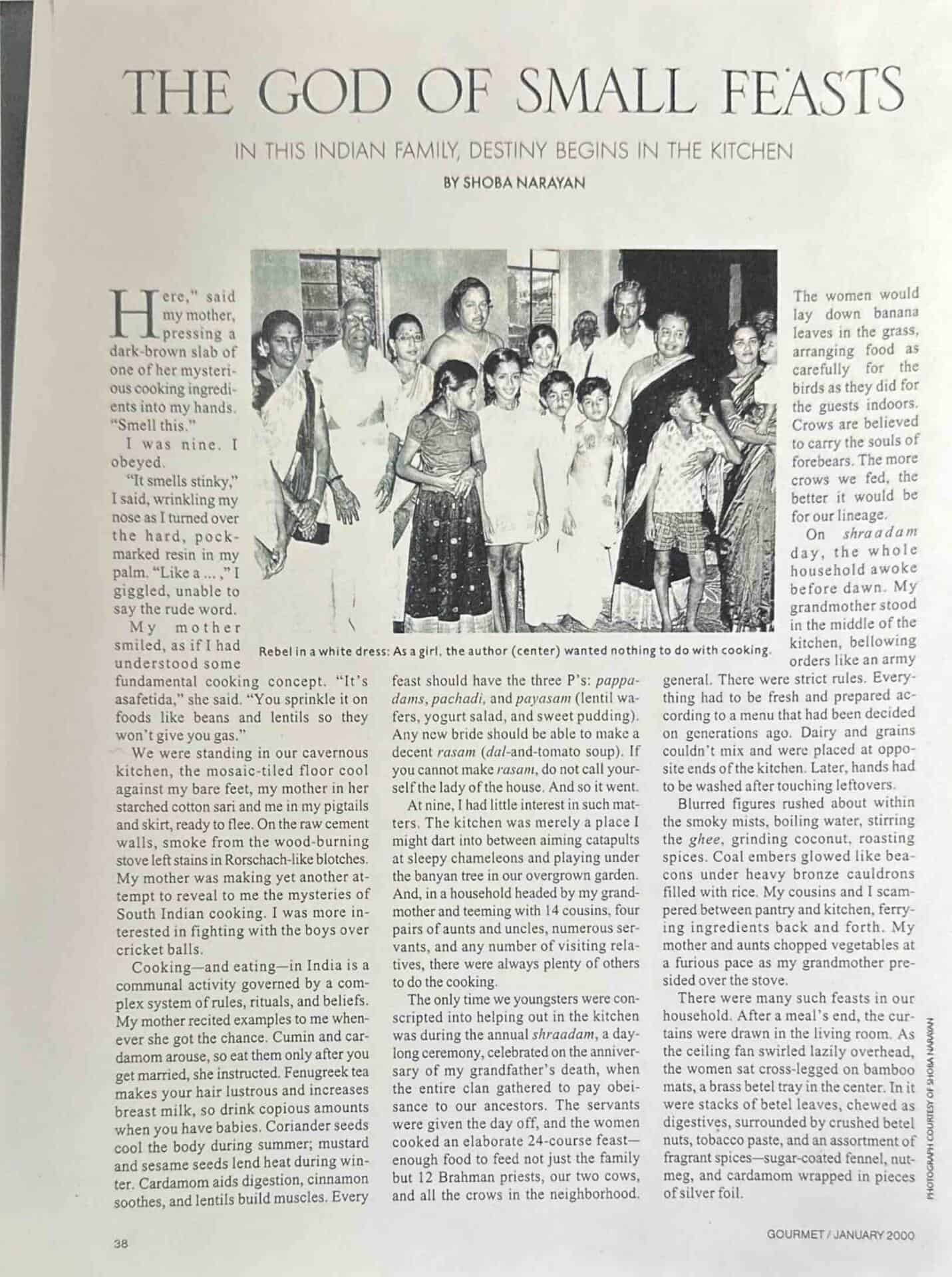

We were standing in our cavernous kitchen, the mosaic-tiled floor cool against my bare feet, my mother in her starched cotton sari and me in my pigtails and skirt, ready to flee. On the raw cement walls, smoke from the wood-burning stove left stains in Rorschach-like blotches. My mother was making yet another attempt to reveal to me the mysteries of South Indian cooking. I was more interested in fighting with the boys over cricket balls.

Cooking—and eating—in India is a communal activity governed by a complex system of rules, rituals, and beliefs. My mother recited examples to me whenever she got the chance. Cumin and cardamom arouse, so eat them only after you get married, she instructed. Fenugreek tea makes your hair lustrous and increases breast milk, so drink copious amounts when you have babies. Coriander seeds cool the body during summer; mustard and sesame seeds lend heat during winter. Cardamom aids digestion, cinnamon soothes, and lent¬ils build muscles. Every feast should have the three P’s: pappadams, pachadi, and payasam (lentil wafers, yogurt salad, and sweet pudding). Any new bride should be able to make a decent rasam (dal-and-tomato soup). If you cannot make rasam, do not call yourself the lady of the house. And so it went.

At nine, I had little interest in such matters. The kitchen was merely a place I might dart into between aiming catapults at sleepy chameleons and playing under the banyan tree in our overgrown garden. And, in a household headed by my grandmother and teeming with 14 cousins, four pairs of aunts and uncles, numerous servants, and any number of visiting relatives, there were always plenty of others to do the cooking.

The only time we youngsters were conscripted into helping out in the kitchen was during the annual shraadam, a daylong ceremony, celebrated on the anniversary of my grandfather’s death, when the entire clan gathered to pay obeisance to our ancestors. The servants were given the day off, and the women cooked an elaborate 24-course feast—enough food to feed not just the family but 12 Brahman priests, our two cows, and all the crows in the neighborhood. The women would lay down banana leaves in the grass, arranging food as carefully for the birds as they did for the guests indoors. Crows are believed to carry the souls of forebears. The more crows we fed, the better it would be for our lineage.

On shraadam day, the whole household awoke before dawn. My grandmother stood in the middle of the kitchen, bellowing orders like an army general. There were strict rules. Everything had to be fresh and prepared according to a menu that had been decided on generations ago. Dairy and grains couldn’t mix and were placed at opposite ends of the kitchen. Later, hands had to be washed after touching leftovers.

Blurred figures rushed about within the smoky mists, boiling water, stirring the ghee, grinding coconut, roasting spices. Coal embers glowed like beacons under heavy bronze cauldrons filled with rice. My cousins and I scampered between pantry and kitchen, ferrying ingredients back and forth. My mother and aunts chopped vegetables at a furious pace as my grandmother presided over the stove.

There were many such feasts in our household. After a meal’s end, the curtains were drawn in the living room. As the ceiling fan swirled lazily overhead, the women sat cross-legged on bamboo mats, a brass betel tray in the center. In it were stacks of betel leaves, chewed as digestives, surrounded by crushed betel nuts, tobacco paste, and an assortment of fragrant spices—sugar-coated fennel, nutmeg, and cardamom wrapped in pieces of silver foil.

The women brushed the tender betel leaves with tobacco paste, filled them with the nuts and spices, then folded the leaves into triangles called paan. They popped these into their mouths, chewing gently until their tongues and teeth were stained red from the opiate combination.

With each paan they chewed, their jokes grew more risqué, their gossip more personal, and their bodies more horizontal. Soon, the room would be full of red-toothed, shrieking, laughing, swaying women that I hardly recognized as the same harassed housewives who were constantly shooing us children out of the way.

I would rest my head on my grandmother’s squishy abdomen and feel her soft flesh rumble as she belly-laughed her way to tears. Although I didn’t realize it at the time, this would be the closest I’d ever come to feeling totally at peace.

Inevitably, however, the conversation would turn toward errant offspring and how young girls ought to learn cooking as preparation for later life. I would sneak a betel leaf and scurry away. I had no intention of being court-martialed by a bevy of relatives trying to entice, entreat, or threaten me into the kitchen.

I continued to spurn cooking into my adolescence. When I reached 14, by some mysterious alchemy—was it genes? destiny?—a passion for the sensuality of food slowly, slowly began to take root. Ever the rebel, I kept it a secret.

Madras, India, 1986. At 18, I have just been accepted into Mount Holyoke College, in South Hadley, Massachusetts, but the consensus in my family is that I shouldn’t go. America is full of muggers and all kinds of criminals, my teenage pest of a brother proclaims. No unmarried girl should venture into such a promiscuous society, my septuagenarian grandmother adds. Why go abroad to study when there are world-class Indian institutions to choose from here? An uncle asks. Get married first, my mother says with finality—then go to Timbuktu if you want.

After days of pleading, the elders relent a bit. I am to cook them a vegetarian feast with the perfect balance of spices and flavors. It is a test, one they are sure I will fail. And in it lies my destiny. If my meal is a success, I can go to the United States.

The elders pick a Friday, considered an auspicious day by many Hindus, for my debut as a cook. Though they’ve given me this advantage, they try to hide their smirks as they inform me that I need not stretch myself. They are not looking for complex masalas or complicated curries, merely good food.

I begin with tender green beans, forgiving and flexible, which I cut into small pieces and sautæ in oil with mustard seeds and urad dal. I sprinkle the beans with desiccated coconut, watching as the thin strips flutter downward: falling tea leaves foretelling my future.

I chop cucumbers, tomatoes, and red onions for the pachadi and douse them in thick yogurt, over which I arrange fresh green cilantro in concentric swirls. Under the yogurt-white landscape the red onions appear like bluish veins. Red tomatoes, white yogurt, and blue onions. Red, white, and blue. Is it an omen, or just my imagination?

I tease some spinach over a low flame until it blossoms into a green as deep and bright as the eye of the ocean—and smile with secret satisfaction. The spinach is for palak paneer, the one dish in my menu that is not from South India and that will stand out as a misfit. Renegade food made by a rebel; the thought pleases me. I puræe the spinach and stir in asafetida, tomatoes, pearl onions, and cubes of creamy fried paneer—fresh cheese with the texture of warm tofu—suppressing a bubble of laughter.

Tomatoes brew in tamarind water with turmeric and salt as I cook red lentils. I blend them in, garnishing the rasam with cilantro, mustard seeds, and roasted cumin. The scent of cilantro perfumes the air and soothes my soul.

Tomato rasam is the vegetarian’s equivalent of chicken soup. It’s the only comfort food I know. When the monsoons ravaged the red earth of my homeland, my grandmother would puræe the rasam with sticky rice and add a spoonful of warm ghee. We would watch the swaying trees arch under the sheets of rain, contentedly spooning the rasam-rice mixture from silver bowls.

I hover over virgin rice, cooking it until each grain is softened but doesn’t stick. I stir in turmeric soaked in lemon juice, then ginger, peanuts, and curry leaves I’ve fried in oil. The rice looks like a painter’s palette. Cadmium yellow speckled with burnt sienna.

As sweet butter turns into golden ghee, the food of gods, the litany I learned at my mother’s knee echoes in my head: Ghee promotes growth, ginger soothes, garlic rejuvenates. My grandfather eluded the cholesterol police by drinking a tumblerful daily and living till 104.

Dessert is a simple payasam, rice pudding, with roasted pistachios, plump rai-sins, and strands of saffron strewn on top. The feast ends with aromatic South Indian coffee, a mixture of ground plantation and peaberry beans with a dash of chicory. I filter the coffee powder through a muslin cloth, then mix it with boiling cow’s milk that froths on top and, following my mother’s prescription, just enough sugar to take out the bitterness but add nothing to the taste.

The elders arrive, resplendent as peacocks in their silk saris and gleaming white dhotis made from spun Madras cotton. Even my teenage cousins are dressed to kill. They survey the ancient rosewood table that totters under the weight of the stainless-steel containers I have filled. I arrange banana leaves on the floor and invite everyone to sit down on the bamboo mats.

My guests pick and sample, judiciously at first. They don’t want to eat, but they can’t stop themselves. They fight over the last piece of paneer, taste overtaking caution. Grandma leans back and belches unapologetically.

I can go to America.

Slurp ! Not a foodie but your article tickled my palate as well as my funny bone ! Am sure you would have enticed the Americans too with all this cooking – being groomed by your grand mom & extended family & your innate culinary interest .

Thank you for spelling out in such an evocative manner how Indian women use food rituals as a way of self-expression. The mother-daughter dynamic at the beginning of your story has a universal appeal. Our mothers are indeed rather skilled at teaching us cultural intricacies without us even noticing, even though as youngsters we are inevitably opposed to them at first.

Sweet food story. Have just finished milk woman of Bangalore so enjoyed reading that you also use banana leaves as plates.

Thanks so much