Artist Sudarshan Shetty and I are sitting on the steps of the Pushya Mahal ghat in Thiruvaiyaru town and chatting. The river Cauvery, so resonant to us south Indians, is flowing in front of us. Flowing is an overstatement. There are islands of sand in between large puddles of water.

This discernment has percolated down to Srinivasan. I first met her in New York over 10 years ago. She came for a few months to study cultural anthropology at Columbia, and art history at Parsons and The New School. I tried securing an apartment for her, but the Fifth Avenue apartment she found—on her own and in two days—was far better. We visited each other. Once, I took her shopping at Bergdorf’s, where she bought French aroma candles and well-chosen accessories. Then we lost touch.

Just before this Independence Day issue, I reached out to her through her son, Gopal, and asked if she would talk about the “TVS brand”. Reluctantly, she agreed. So here we are at her home, talking over fresh juice. The staff, clad in white, hovers nearby as she talks about growing up in the Mylapore area of Chennai and volunteering for the freedom movement as a girl of 13. Srinivasan comes from a family of scholars and professionals and when she got married, she was taken in and “spoilt” by her mother-in-law, Lakshmi, a woman of simple tastes, who always wore khadi and cotton saris.

“We were never given diamonds or silks and there was no glamour or personal amassment of wealth,” says Srinivasan. “Now all that has changed with spouses coming in from different parts.” Both her in-laws had just six sets of clothes which they would use and give away before acquiring the next set. Today, she says: “We all have closets and closets of things that we rarely use. But all this happened only after I moved to Madras.”

The few luxuries that the family enjoyed in the early days were fresh fruits and vegetables and a personal dhobi (washerman). “My father-in-law used to say, ‘Vaithiyannu kudukarathukku bathila vanniyannukku kodu(Instead of giving money to the doctor, give it to the fruit merchant)’, so we always took care of what we ate. And cleanliness was very important.”

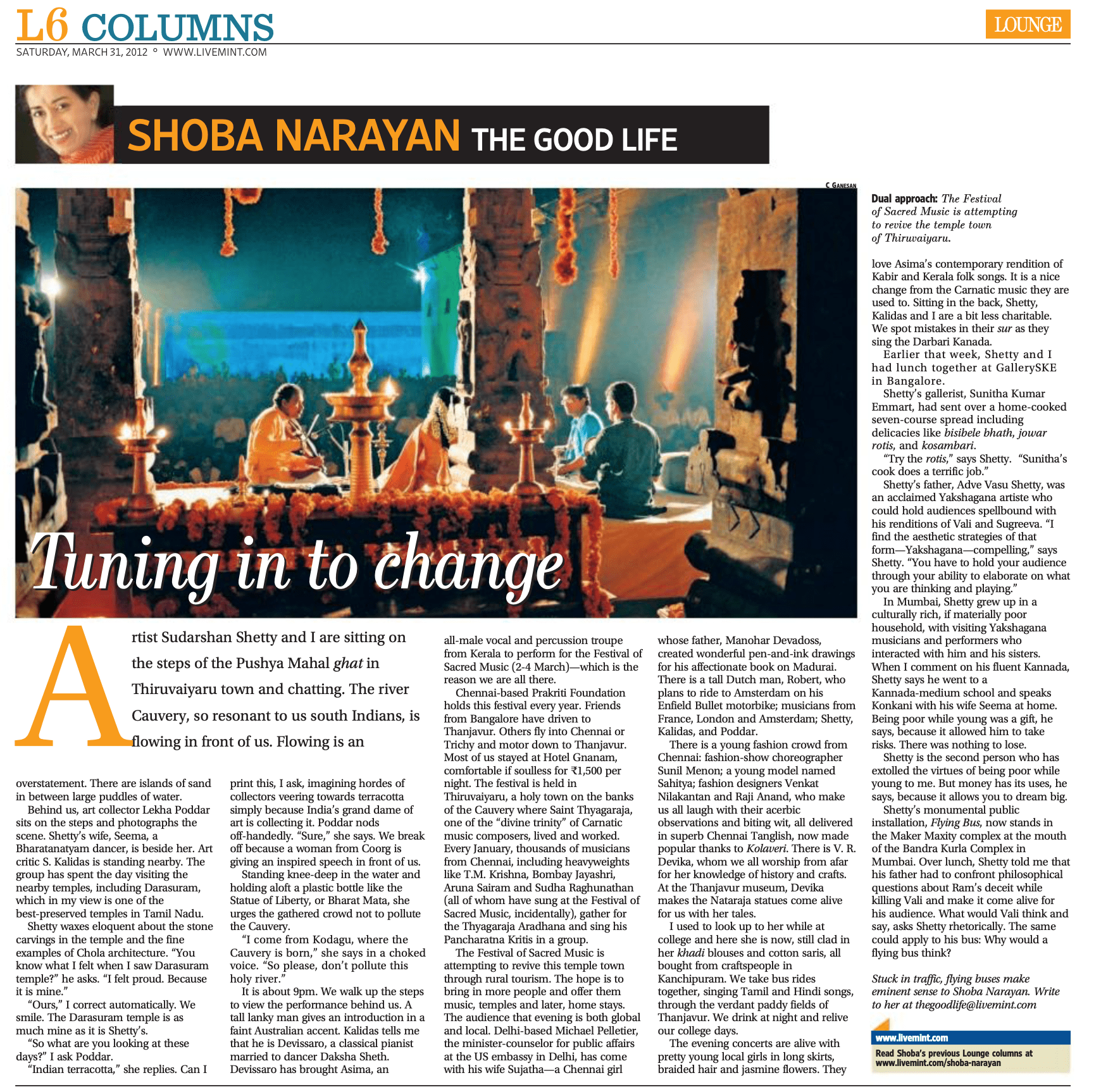

The Festival of Sacred Music is attempting to revive this temple town through rural tourism. The hope is to bring in more people and offer them music, temples and later, home stays. The audience that evening is both global and local. Delhi-based Michael Pelletier, the minister-counselor for public affairs at the US embassy in Delhi, has come with his wife Sujatha—a Chennai girl whose father, Manohar Devadoss, created wonderful pen-and-ink drawings for his affectionate book on Madurai. There is a tall Dutch man, Robert, who plans to ride to Amsterdam on his Enfield Bullet motorbike; musicians from France, London and Amsterdam; Shetty, Kalidas, and Poddar.

There is a young fashion crowd from Chennai: fashion-show choreographer Sunil Menon; a young model named Sahitya; fashion designers Venkat Nilakantan and Raji Anand, who make us all laugh with their acerbic observations and biting wit, all delivered in superb Chennai Tanglish, now made popular thanks to Kolaveri. There is V. R. Devika, whom we all worship from afar for her knowledge of history and crafts. At the Thanjavur museum, Devika makes the Nataraja statues come alive for us with her tales.

I used to look up to her while at college and here she is now, still clad in her khadi blouses and cotton saris, all bought from craftspeople in Kanchipuram. We take bus rides together, singing Tamil and Hindi songs, through the verdant paddy fields of Thanjavur. We drink at night and relive our college days.

The evening concerts are alive with pretty young local girls in long skirts, braided hair and jasmine flowers. They love Asima’s contemporary rendition of Kabir and Kerala folk songs. It is a nice change from the Carnatic music they are used to. Sitting in the back, Shetty, Kalidas and I are a bit less charitable. We spot mistakes in their sur as they sing the Darbari Kanada.

Earlier that week, Shetty and I had lunch together at GallerySKE in Bangalore.

Shetty’s gallerist, Sunitha Kumar Emmart, had sent over a home-cooked seven-course spread including delicacies like bisibele bhath, jowar rotis, and kosambari.

“Try the rotis,” says Shetty. “Sunitha’s cook does a terrific job.”

Shetty’s father, Adve Vasu Shetty, was an acclaimed Yakshagana artiste who could hold audiences spellbound with his renditions of Vali and Sugreeva. “I find the aesthetic strategies of that form—Yakshagana—compelling,” says Shetty. “You have to hold your audience through your ability to elaborate on what you are thinking and playing.”

In Mumbai, Shetty grew up in a culturally rich, if materially poor household, with visiting Yakshagana musicians and performers who interacted with him and his sisters. When I comment on his fluent Kannada, Shetty says he went to a Kannada-medium school and speaks Konkani with his wife Seema at home. Being poor while young was a gift, he says, because it allowed him to take risks. There was nothing to lose.

Shetty is the second person who has extolled the virtues of being poor while young to me. But money has its uses, he says, because it allows you to dream big.

Shetty’s monumental public installation, Flying Bus, now stands in the Maker Maxity complex at the mouth of the Bandra Kurla Complex in Mumbai. Over lunch, Shetty told me that his father had to confront philosophical questions about Ram’s deceit while killing Vali and make it come alive for his audience. What would Vali think and say, asks Shetty rhetorically. The same could apply to his bus: Why would a flying bus think?

Stuck in traffic, flying buses make eminent sense to Shoba Narayan. Write to her at [email protected]

Also Read | Shoba’s previous Lounge columns

Leave A Comment