My Life as a Geisha for Condenast Traveler US edition

by

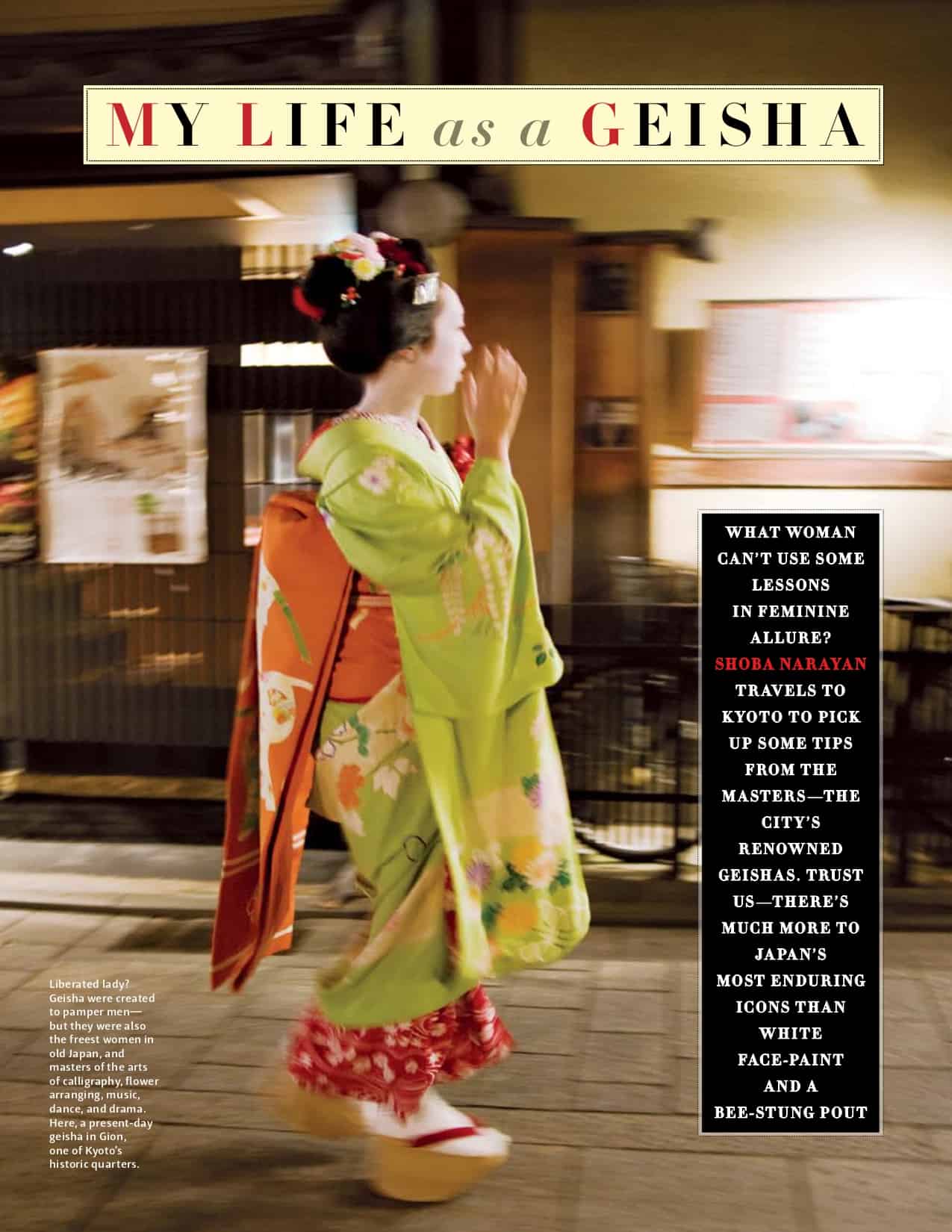

Liberated lady? Geisha were created to pamper men—but they were also the freest women in old Japan, and masters of the arts of calligraphy, flower arranging, music, dance, and drama. Here, a present-day geisha in Gion, one of Kyoto’s historic quarters.

What woman can’t use some lessons in feminine allure?

Shoba Narayan travels to Kyoto to pick up some tips from the masters: the city’s renowned geishas.

Trust us. There’s much more to Japan’s most enduring icons than white face-paint and a bee-stung pout.

I have come to Japan to learn about allure. I’ve been married for seventeen years, and while my marriage isn’t falling apart, it is fraying at the edges: a victim of minutiae like leaky taps, lost airline tickets, and PTA meetings. Nowadays when I ask my husband a fairly innocuous question such as, “Does this green dress suit me?” he gets this deer-in-the-headlights expression. I want Ram to look at me without fear and with adoration. So I have come to Japan to learn about feminine allure from its acknowledged masters: the geisha.

Suzuno-san thinks I shouldn’t even be asking questions. Suzuno-san is a Tokyo geisha. Like most Japanese, she is slim and beautiful with high cheekbones, Dior-red lips, and a chignon worn at the nape, which the Japanese consider the sexiest part of a woman. This is why geisha and maiko(apprentice geisha) wear their kimono low on the neck, the nape revealed.

Suzuno-san is in her forties, maybe fifties. I cannot ask. Geisha don’t reveal their age anyway. She teaches etiquette and bemoans the rising informality of her culture. “These manners are part of who we are,” she says. “It is what defines us as Japanese.”

We meet at Fucha-ryori Bon, a lovely restaurant with tatami-lined cubicles inside which patrons can have lunch in rice paper-screened privacy.

Over the next hour,

Suzuno-san says that peppering a man with questions is a big no-no, something she tells all her maiko. Questions put a man on the defensive. “I may know a lot about politics, but I won’t reveal it,” she says. “Instead, I will draw him out.”

This whole notion of playing dumb bothers me, and I tell her so. Hasn’t she heard of feminism? Her interpretation is different. She plays dumb not because she is a woman and he is a man. She does it because she is a professional and he is her client. It has more to do with hierarchy than gender. Japanese men play dumb with their clients too.

It is a smart answer, but it doesn’t help me with my marriage. I can’t stop asking my husband questions even though I know it puts him on the defensive. I can, however, learn what Suzuno-san calls respect for both humans and objects. Respect the tatami by leaving your shoes outside. When you cross a room, don’t just blunder across. Go behind people so that their conversations are not disturbed. Cover your mouth when you giggle. When you enter a tatami room, don’t just walk in. Sit on your haunches and slide across the threshold, then bow deeply to your host while still kneeling.

We finish lunch. My interpreter and I drop Suzuno-san at her street corner before speeding off. I turn around and watch her slide across the broad avenue. With her floral-pink kimono and erect carriage, she looks regal. Alluring.

The dictionary defines allure as “the power to entice or attract through personal charm,” which has more to do with gait and bearing than with beauty.

The geisha are masters of allure. This, I believe, is why we are fascinated by them. It isn’t that they are beautiful, although many of them are. Beauty is a wild card anyway, beyond our control. Sexy, after a certain age, borders on tawdry. Mystique is too much work. But allure, as the geisha so magnificently prove, can be taught and learned. Just like etiquette.

The Japanese call this iki, an aesthetic ideal that implies subdued elegance. Iki emerged in the eighteenth century as a kind of reverse snobbery that the working class developed toward the affected opulence of their rulers. Iki pits subtlety against gaudiness, edginess against beauty, relaxed simplicity against gorgeous formality. Loosely translated, iki means being chic or cool, but its nuances are particular to Japan—curves, for instance, are not iki but straightness is. Iki combines sassiness with innocence, sexiness with restraint. Geisha, with their giggly coquettishness, are emblematic of iki, or aspire to be.

Kyoto represents the apogee of the iki aesthetic, and that is where my journey begins. At its center is the vast Imperial Palace compound, which is surrounded by a grid of neighborhoods, a style of urban planning inspired by the Tang Dynasty’s capital city, Chang’an (now Xi’an). Bordered by mountains on three sides, this neat, green, low-rising city of 1.46 million people is almost at the geographical center of Honshu, Japan’s largest island. With its graceful Zen temples, crooked cobblestone streets, Shinto shrines, moss-covered gardens, and the meandering Kamo River, it is the country’s spiritual and cultural heart. Kyoto is the quintessential Japan, in which every icon and art form that we associate with the country blooms into perfection.

Kyoto represents the apogee of the iki aesthetic, and that is where my journey begins. At its center is the vast Imperial Palace compound, which is surrounded by a grid of neighborhoods, a style of urban planning inspired by the Tang Dynasty’s capital city, Chang’an (now Xi’an). Bordered by mountains on three sides, this neat, green, low-rising city of 1.46 million people is almost at the geographical center of Honshu, Japan’s largest island.

With its graceful Zen temples, crooked cobblestone streets, Shinto shrines, moss-covered gardens, and the meandering Kamo River, it is the country’s spiritual and cultural heart. Kyoto is the quintessential Japan, in which every icon and art form that we associate with the country blooms into perfection. In AD 794, the dour Emperor Kammu, freaked out by a series of accidents and natural disasters, moved the imperial capital from Nara to nearby Kyoto. He named his new capital Heian-kyo, Place of Peace and Tranquillity. Here, during the country’s thousand years of relative seclusion from neighboring China and Korea, courtiers composed poetry, painted landscapes, drank sake, and held moon-viewing parties in autumn. The elegant Lady Murasaki wrote The Tale of Genji, widely considered the world’s first novel (its influence still permeates Japan).

The city’s fortunes wavered according to the whims of warring rulers, and Kyoto was taken over by successive feuding clans, shogunates, and armed samurai until the capital moved to Tokyo in 1868. This checkered history has contributed mightily to Kyoto’s layered character. Within Japan, the city is viewed with a combination of envy and disdain. Ask a Tokyo teenager what he thinks of Kyoto-ans and he will use words like snobbish and conservative. Kyoto people never talk straight, he will say. They don’t reveal their feelings, and consider you a native only if you have lived there for generations. Theirs is Japanese reserve multiplied by ten.

At twilight, the city comes alive. Swarms of jeans-clad office workers make way for kimono-clad matrons hurrying off to buy pickles and eel at the bustling Nishiki Market. Every now and then, a geisha appears, standing incongruously under a neon sign advertising lingerie.

For a modern feminist like me, it is difficult not to view the geisha culture as archaic and sexist—and perhaps it is. But having grown up in the East, I know that perception doesn’t equal reality. Contradictions exist within cultures—particularly in Japan, where myth and mystique are like a silken skein that shows but doesn’t reveal. Yes, geisha were created to pamper Japanese men, but they were also the freest women in old Japan. “Successful geisha were strong-willed businesswomen,” says Japan expert Alex Kerr. “Unlike the typical sheltered Japanese wife, they’d been out in the world.”

An American who speaks fluent Japanese, Kerr is an acclaimed author, calligrapher, and art collector. I meet him at an Origin Arts workshop he conducts in Kyoto. Superbly designed and executed, his experiential workshops offer insights into the traditional Japanese arts: tea ceremony, calligraphy, flower arranging, music, dance, and drama—all arts that a geisha must master. The word gei-sha, after all, means arts person, and mai-ko means dancing girl. For two days, I will receive some of the training that the geisha undergo for years.

Geisha have always played a key role in preserving the arts. This was how they differentiated themselves from the courtesans of the Pontocho pleasure quarters—by studying the arts with a discipline that would give a Russian ballet dancer a complex. In winter, it is said, they would dip their hands in icy water and then sit outside in the freezing cold and play the samisen, a traditional stringed instrument, until their frozen fingers bled.

I remember this during my next lesson, which involves quite literally turning myself into a geisha. Kyoto has several shops that offer to transform you into a geisha or, for men, a samurai. My guide, Koko Ijuin, tells me that they are very popular with visiting Koreans and Chinese.

Koko-san, as I call her, is a dainty woman who spent part of her childhood in America. Trained in the classical Japanese arts, she tells me that there is a proper way to do everything, including opening a fusuma, or sliding door. It goes like this: Kneel directly in front of the fusuma,; place your fingertips in the handle; slide the fusuma, open two inches; place the same hand on the frame, about nine inches above the floor; push the fusuma open halfway; change your hand and push the fusuma, open the rest of the way; stand up and back away. I am speechless at the level of precision. This, I think, is the secret of Japan: to see greatness in small things and smallness in great things.

Yume Miru Yume, where Koko-san takes me, is a tiny makeup studio near a shrine. Three women descend on me like fluttering sparrows and whisk me up a flight of stairs to the kimono room. The Japanese love of seasons is reflected in their kimono, and because it is spring, the ones I am shown are decorated with azaleas, weeping willows, and cherry blossoms. I choose a royal-blue kimono with red and green flowers climbing up the sides. My obi, the wide brocade belt tied around the kimono, is black and gold. It is thirteen feet long. Old Japan was designed for a woman wearing a kimono—the squatting toilets, temple steps, and furniture-less houses. Now, they are all but invisible in the streets.

Two attendants dress me, and then we adjourn to the makeup studio below, where the kao-shi, or face master, smears a white herbal paste all over my face and neck. My lips are drawn thinner than they are and are painted bright red, like a rosebud. Then comes a wig with an elaborate hairstyle—not the famous split-peach one, suggestive of the vagina, but another updo. The hairstylist adorns my wig with lacquer combs, tortoiseshell bow-clips, and hanging silk flowers.

Finally, I am permitted to look in the mirror.

An exotic stranger stares back—white face, red lips. I look Japanese.

“Kawaii!”, exclaim the girls. “Cute!”

Kyoto represents the apogee of the iki aesthetic, and that is where my journey begins. At its center is the vast Imperial Palace compound, which is surrounded by a grid of neighborhoods, a style of urban planning inspired by the Tang Dynasty’s capital city, Chang’an (now Xi’an). Bordered by mountains on three sides, this neat, green, low-rising city of 1.46 million people is almost at the geographical center of Honshu, Japan’s largest island. With its graceful Zen temples, crooked cobblestone streets, Shinto shrines, moss-covered gardens, and the meandering Kamo River, it is the country’s spiritual and cultural heart. Kyoto is the quintessential Japan, in which every icon and art form that we associate with the country blooms into perfection.

In a.d. 794, the dour Emperor Kammu, freaked out by a series of accidents and natural disasters, moved the imperial capital from Nara to nearby Kyoto. He named his new capital Heian-kyo, Place of Peace and Tranquillity. Here, during the country’s thousand years of relative seclusion from neighboring China and Korea, courtiers composed poetry, painted landscapes, drank sake, and held moon-viewing parties in autumn. The elegant Lady Murasaki wrote The Tale of Genji, widely considered the world’s first novel (its influence still permeates Japan).

The city’s fortunes wavered according to the whims of warring rulers, and Kyoto was taken over by successive feuding clans, shogunates, and armed samurai until the capital moved to Tokyo in 1868. This checkered history has contributed mightily to Kyoto’s layered character. Within Japan, the city is viewed with a combination of envy and disdain. Ask a Tokyo teenager what he thinks of Kyoto-ans and he will use words like snobbish and conservative. Kyoto people never talk straight, he will say. They don’t reveal their feelings, and consider you a native only if you have lived there for generations. Theirs is Japanese reserve multiplied by ten.

At twilight, the city comes alive. Swarms of jeans-clad office workers make way for kimono-clad matrons hurrying off to buy pickles and eel at the bustling Nishiki Market. Every now and then, a geisha appears, standing incongruously under a neon sign advertising lingerie.

“Kawaii!” is a word used to describe maiko—their girlish giggles and presumed innocence. An American woman I meet later tells me that she detests the word; to her, it seems to wipe out a century of feminism. Japanese men, however, love this non-threatening cuteness. In fact, young maiko are told not to look men in the eye because it is disrespectful. Instead, their eyes “skitter,” says Koko-san.

It is showtime. I slip my feet into the high-heeled geta clogs and step into the sunshine. People start taking photographs—me holding a fan, an umbrella; simpering and skittering. I hobble up the cobblestone street to the Yasaka Shrine. “Softly,” says Koko-san. “Don’t stride. Make a figure eight with your feet.” Koko-san calls the elegant shuffle of the Japanese ladies shinayakasa. It suggests softness and ripples—like the waves, with one movement blending into the other. Young Japanese girls who have never worn a kimono “do not experience such movement,” says Koko-san. “This makes them look very ugly when they put on the kimono for the first time.” For a few minutes, I achieve my fantasy, if not my goal. I am a Kyoto geisha, but it is only as deep as my painted white skin; I have not yet been able to get under their skin and learn their secrets.

That evening, I walk through the five geisha districts of Kyoto, also known as hanamachi, or flower towns. Light spills through the lattice screens and dapples the puddles in the road. Beautifully made-up geisha and maiko hurry between teahouses, going from one appointment to another. Tourists’ cameras click. The scene is at once thoroughly modern and utterly timeless.

The geisha’s karyukai, or “flower and willow world,” is both exacting and secret—one that prizes discretion (geisha rarely marry and if they do, they retire and never reveal the father of their child or children), yet is open to misinterpretation. When the American GIs occupied Japan, they stood in Tokyo’s Ginza district and chanted for “geesha girls,” or prostitutes. Today’s geisha go to great lengths to explain that they are sophisticated entertainers, not prostitutes. They may hint at their sexuality using double entendres and sexual jokes delivered with the most innocent of faces; they may draw out a man’s sorrows by listening to him sympathetically and pouring more sake; but they certainly do not sleep around. Rather, they occupy a rarefied realm in which women are both divas and directors.

The earliest geisha were in fact men who played the role of court jester to the feudal lords of the thirteenth century. During the Edo period, merchants, shoguns (army commanders), samurai, and feudal lords spent their time traveling between Tokyo, the new capital, and Kyoto, where they might remain for months finishing deals or monitoring projects. Kyoto teahouses were built to entertain these travelers. Many of the early geisha were daughters of these teahouses, a tradition that continues to this day, with geisha being “adopted” by the okiya (teahouse) mother—okaasan.

Naosome, the geisha I spend an afternoon with, has been adopted by the Nakazato teahouse. She is all of nineteen. Our meeting is almost a roundtable conference: me, Koko-san, the fixer who got us the interview—a beautiful lady called Hamasaki-san—Naosome, the okaasan, and her assistant, who brings in cups of green tea.

Naosome is of erect bearing, exquisitely polite, charming, and, for a geisha, candid. Actually, she is not yet a geisha but will be in a few weeks. The fact that she is becoming a geisha at nineteen shows how good she is at what she does, Koko-san says later. This means that she has found a danna, or patron, who will fund her studies and perhaps have a relationship with her. In her orange kimono with her scrubbed face and frequent giggles, Naosome looks far too young to have a danna, let alone be a geisha. When I mention how young she looks, she laughs. Compared with her friends back home in her village, she is very mature, she says. She has been to fancy restaurants and parties; met and interacted with important businessmen and dignitaries. “I can call them oniisan [big brother], laugh and joke with them,” she says. “Plus I get to wear a kimono, practice my dance, and live in this world of beauty.”

By now, I am starstruck by her poise. What, I ask, does she do to maintain her beauty? Yoga, a special diet? She giggles again. “I only avoid things that affect my work.” She pauses for a beat. “Such as garlic,” she ends with great comic timing. The room erupts in laughter.

I ask the okaasan how she picks the girls that she molds into geisha. She pauses for a moment and lets out a heavy sigh. “They have to be beautiful, of course,” she replies, “and disciplined, because they work long hours with few holidays. They have to be smart and learn quickly how to play instruments, dance, do tea ceremony.” After all, it takes three years to just get the basic stuff right: posture, hand gestures, and what she calls “piling up experiences.” But in the end, it is a gut feeling that she gets. “A geisha is like the sun,” says the okaasan. “When she walks into a room, it becomes brighter.”

I sigh—at the poetry of the words, at the audacity of my attempt to emulate the geisha. I can try to sit ramrod straight all I want. I can even learn how to put on makeup. But flirting with decorum requires skill; innuendo while maintaining propriety requires talent. A good geisha knows when to flirt, and how to do the right thing at the opportune moment—like Brooke Astor and Nan Kempner, who would have made excellent geisha. Geisha have an uncanny ability to light up a party and switch on the atmosphere; they understand and prize the art of conversation. They know exactly what to say to the shy wallflowers to draw them out without making them feel self-conscious. The Japanese call this _kikubari_paying careful attention to others and understanding their desires before they vocalize them.

One evening, Naosome entertains me and my children at her teahouse. My daughters are six and eleven, dressed in recently purchased kimonos and looking slightly bemused by the unfamiliar Japanese food in front of them. Right off the bat, my six-year-old announces that the food tastes “weird.” How will Naosome handle us? She doesn’t speak English, and we don’t speak Japanese. The evening is going to be a washout, I decide.

What Naosome does—after treating us to a traditional fan dance—is play games. She teaches my girls a song that provides the background beat to several rock-paper-scissors-like games. Within minutes, my kids are entranced—by Naosome’s grace, her laughter, the softness of her touch as she hugs them when they win. The evening passes in a whirl of perfume and giggles.

“Most foreigners think geisha only play games,” says Sayuki, an Australian geisha, whose condition for meeting me is that I will list her Web site, sayuki.net. Such straightforward negotiation seems normal in modern business but comes across as blunt in a world where a geisha’s time is measured by the number of incense sticks used while she entertains. In the wispy smoke trailing from the stick lies the key to an entire subculture.

It is near the end of my time in Japan, and while I know I shouldn’t say this—being Indian, I’ve been treated to my own share of cultural stereotypes—I am convinced more than ever that Japan’s aesthetic is singular, so distinct that it can make the country feel, at times, almost impenetrable. Consider: Most ancient civilizations base their notions of beauty on symmetry. Think of the Taj Mahal, the Pyramids, the Parthenon. But Japan worships asymmetry. Most Japanese rock gardens are off-center; raku ceramics have an undulating unevenness to them.

What’s also unusual about Japan is how highly evolved, almost modern, its ancient aesthetic traditions are. Fragmentation, for instance, is a modern photographic idea, but the Japanese had it figured out aeons ago. Japanese paintings, for example, often depict a single branch instead of a tree. A fragmented moon hidden by clouds is considered more beautiful than a full in-your-face moon. They call this mono no aware, which implies an acute sensitivity to the beauty of objects, the “ahhness of things,” as the Japanese would have it. Mono no aware attunes people to the fragile and the transient. It values the soft patina of age more than the sparkle of newness.

Another important concept in Japanese aesthetics is wabi-sabi, which again is contrarian. The Japanese are a perfectionistic people, yet wabi-sabi honors the old and the vulnerable; the imperfect, the unfinished, and the ephemeral. While other ancient cultures emphasized permanence and endurance (Indian stone sculptures were built to last forever, as were the Sphinx and the Sistine Chapel), Japan celebrated transience and impermanence. The tea ceremony, which is often considered the acme of Japanese arts, leaves behind nothing but a memory. Wabi-sabi connotes “spiritual longing” and “serene melancholy,” which sounds pretentious but makes perfect sense when you visit rural Japan. The cherry blossoms are ephemeral and therefore wabi-sabi; the tea ceremony connotes loneliness and longing for a higher spiritual plane, hence it is wabi&-sabi. The old cracked teapot, the weathered fabric, the lonely weeping willow are all wabi-sabi.__

Geisha, however, are anything but. “Just as the tea ceremony represents the wabi-sabi aspect of Japanese culture, geisha represent the opposite—the effervescence of the culture,” says Toru Ota, a scholar and confectioner who teaches at Kyoto Women’s University and owns Oimatsu, one of Kyoto’s best sweets shops. I meet Ota-san above his shop, where bejeweled pastries in candy pink, baby blue, and melting orange are displayed like works of art. A slim man who vaguely resembles Jackie Chan, Ota-san looks ascetic but is in fact an aesthete, pursuing a life revolving around beauty. He is a painter, a tea master, a confectioner, and a patron of the arts—a Japanese Renaissance man. He invites me to witness a tea ceremony at his rural retreat in Ohara, an hour outside Kyoto, for my final lesson in the Japanese arts.

The tea ceremony is exquisite. For those accustomed to the casualness creeping into the modern world, it can seem long-winded and needlessly formal. There are at least sixteen steps, including cleaning the utensils, admiring the teapot, exchanging greetings, eating the tea sweets, and then drinking the matcha (strong) and sencha (light) tea. In ancient Japan, Chado, or the Way of Tea, was considered the essence of civilization.

In a dark tatami room lit by candles, Ota-san mixes powdery matcha tea with hot water and offers it to us in a bowl. Just as I am about to sip, he casually lets it drop that the bowl I am drinking from is worth a million dollars. I carefully put it down, and we all laugh. The next round of tea, which is more dilute, is offered in a bowl that he picked up in Brazil, he says. It is almost worthless, he says, and laughs.

I gaze at the bowl from Brazil. The two countries could not be more different. Brazil, with its colorful, straightforward exuberance, is extroverted and open. Japan, with its penchant for gray, its reserve and formality, is as yin as Latin America is yang. I try to picture Ota-san at Copacabana Beach. It is impossible.

Which is the best tea ceremony you’ve ever done? I ask. I expect him to mention one that he did for knowledgeable Japanese scholars who knew the various steps of the tea ceremony. By now, I am able to intuit that a tea ceremony can be like a symphony—if all the players know what to do, the experience can be sublime. Ota-san has performed the tea ceremony for famous personalities including architect Tadao Ando and fashion designer Issey Miyake, both of whom were guests in the very tatami room I am kneeling in. So which is your favorite tea ceremony? I press. “This one,” replies Ota-san.

His answer reminds me of a Zen koan, or riddle. Ota-san tells me that he gears each tea ceremony to the guests. The scroll, the flowers, even the choice of tea utensils is based on what he thinks they will like.

“But how do you know what they will like?” I ask.

“I look at their shoes,” he replies. A riddle-like answer. Much later, Ota-san drives me back into Kyoto in his Mercedes. It is pitch-dark. The road winds. A stream gurgles nearby. We are happy. We chat about Barack Obama, Nepali restaurants, and Kyoto’s beauty.

“Enjoy the light spilling through the latticework,” Ota-san says as he drops us at a street corner. “That’s the beauty of Kyoto.”

It has been two months since I got home, and the geisha of Japan still influence my thinking. I pay attention to how I walk; to my movements, whether they are compact and graceful. These are small things, you might say. But to the Japanese, the small is big; the simple is profound. I am still feminist, but Japan seems to have rubbed off the edges. I tolerate stuff from my husband that I previously wouldn’t have. Again, it is small things.

Yesterday, for instance, my husband ranted about our new puppy. She is peeing all over our apartment and driving us nuts. Over dinner, my husband lectured me about how I should fix the problem. In my previous avatar, I would have lectured him right back. Why is the puppy my headache? I would have asked, and gone on a tirade about shared chores and equality in marriage. The whole thing would have spiraled downward and out of control.

Post-Japan, I just listened to him vent. The man is distressed, I thought. What would a geisha do? I wondered. And so I shut up and let him get it all out.

I can’t say that I’ve become more alluring after my time in Japan, but I’ve certainly become more patient. I try to appreciate the present and watch the moon_—wabi-sabi_, you know. Allure can be a sideways glance, a hand gesture, or just listening. Allure can be the simple realization that I am not letting down a whole generation of feminists by being more attentive to my husband. For that, I have the geisha to thank.

Kyoto: Where to Stay, Eat and Play

Japan, as all first-time travelers there can attest, can be difficult to navigate. My trip to Kyoto was arranged by the Tokyo-based Michi Travel Japan, which specializes in tailor-made luxury experiences. Although many companies offer geisha-oriented itineraries, I found Michi not only the most affordable but also the most flexible (and all of its staff speak fluent English). Customized geisha tours aren’t cheap, but the experience is, of course, singular (81-3-5213-5040; michitravel .com; tours, $860$1,050).

The country and city code for Kyoto is 81-75. Prices quoted are for October 2009.

Lodging

There are three Western-style hotels of note in Kyoto: The posh Hyatt Regency has simple functional rooms with kimono- fabric accents (541-1234; doubles, $260$480); the 121-year-old Okura’s sumptuous European interiors include a variety of restaurants serving everything from pasta to teppanyaki, or griddle-cooked food (211-5111; doubles, $420$680); and a serene Japanese garden, hiking trails, and a “Philosopher’s Walk” save the otherwise standardissue Westin Miyako(771-7111; doubles, $185$375). Among ryokans, or traditional inns, the Hiiragiya is considered the best, with spacious tatami rooms, en suite bathrooms, and fine kaiseki cuisine (221-1136; doubles, $368$495 per person, including breakfast and dinner). Highly perfumed with citron, the Yuzuyahas a public bath and considerate service (605-0000; doubles, $330$513 per person, including breakfast and dinner). For an entirely different experience, the Iori Trust, a nonprofit preservation group, rents out traditional machiya, or shophouses, that have been restored and fitted with modern conveniences (352-0211; machiya, $63$415 per person).

Dining

Kyoto has numerous Japanese specialty restaurants serving tempura, teppanyaki, hot pot, sushi, and kaiseki. Its yudofu (tofu with grated ginger and other garnishes) is famous, as are its soba (buckwheat) noodles. Most convenience stores carry bento boxes with reasonably priced food. Kaiseki is at the other end of the spectrum, consisting of elaborate multiple-course meals of seasonal ingredients that are beautifully presented.

Once a princely residence, the Yoshida Sanso is now a boutique inn serving incredible kaiseki (91 Yoshida Shimo-ooji-cho, Sakyo-ku; 771-6125; set menu, $175). Tempura Yoshikawa has amazingly light and flavorful morsels of deep-fried fish and vegetables (Tominokoji-dori Oike-sagaru, Nakagyo-ku; 221-5544; prix fixes, $60$200). Hyotei, near the Nanzenji Temple, serves refined traditional dishes such as quail rice porridge, sashimi, grilled skewers, and bento lunches (35 Kusakawa-cho; 7714116; set menus, $90$200). In the atmospheric Gion district, Mikaku is famed for its teppanyaki made from the best Kobe beef in town (Nawate Dori, Shijoagaru, Gion; 5251129; set menu, $225). For inventive kaiseki with a hint of French flavor, try Giro Giro Hitoshina (420-7 Nanba-cho, Nishi Kiya-machi-dori; 343-7070; set menu, $175). Finally, Scorpione Kichiu blends Japanese ingredients into pizza recipes on a terrace overlooking the Kamo River (133-140-18 Saito-cho, Nishi ishigaki-dori; 354-9517; set menus, $58$86).

Activities

Origin Arts does a wonderful survey of traditional geisha arts including the tea ceremony, calligraphy, flower arrangement, noh drama, martial arts, kyogen comedy theater, and more (365-0722; kyoto-half-day program, from $528). ** Wak Japan** conducts classes in origami, kimonowearing, Japanese dance, cookery, and so on, either in its offices or on home visits (212-9993; classes, $45$200). Under the auspices of Ren Produce, tea master Toru Ota and incense expert Yoshihiro Hamasaki arrange private tea ceremony experiences at ** ” Ota’s rural retreat ** in Ohara. They also offer a variety of classes, private meetings with geisha, and visits to shrines and theaters (864-9700; ren- classes, $75$400).

Stroll down Shijo Street, Gion’s main thoroughfare, and you’ll come across a number of shops selling geisha accessories: fans, hair clips, ornaments, and face paint. If you really want to go native, stop by Yume Miru Yume, one of the many makeup studios in Kyoto that will dress you up as a geisha. Men can become samurai warriors (541-7069.

Reading

Lonely Planet’s Kyoto is useful for its succinct historical information and suggested daily itinerariesless helpful are its restaurant and hotel reviews ($23). Arthur Golden’s novel, Memoirs of a Geisha, is a great primer on Kyoto and the prewar heyday of the geisha (Vintage, $15). The geisha Mineko Iwasaki, who provided much of the material for Golden’s book, has written her own memoir, Geisha: A Life (Simon & Schuster, $15). Liza Dalby, the first Westerner to become a geisha, talks about her experience with insight and respect in Geisha (University of California Press, $25). The Tale of Genji, written in the early eleventh century by the noblewoman Murasaki Shikibu and often considered the world’s first novel, is a must-read for anyone traveling to Japan (Penguin, $28).

Might be this blog’s best blog on the web..