Condenast Traveler’s October Issue has two stories that I reported, one on Kyoto and one on Mumbai.

The printed version is at the below link. This is a 5000 word feature on Mumbai for Condenast Traveler US edition.

It’s nothing if not a city of contrasts. It’s ancient and modern, dirt poor (home to Asia’s second-largest slum) and filthy rich (stomping ground for countless millionaires). It parties till dawn yet still prays at daybreak. It has nightclubs and temples, socialites and mystics. It’s the most densely populated metropolis on earth, and it has a beach for a backyard. Some say it’s too fast, too big, too muchand not to be missed. It even has two names.

Mumbai…Bombay….

It’s Mumbai, Yaar!

I

am going to Bombay to become a movie star. Like millions of others who arrive each day in this island-city by car, plane, bus, or boat, I too have my Bombay dream. I am comely, buxom even (thanks to Wonderbra), and I can giggle and jiggle with the best of them. Age is an issueI am forty-twobut there’s nothing a nip and tuck won’t fix. So I am going to Bombay to become a movie star. Why not?

Every country in the world, if it is lucky, has a city that allows people to create such gauzy fantasies unfettered by the grim shackles of reality. It would be wrong to say that these cities offer their citizens “the space to dream,” for most such placesRio, Tokyo, Cairo, and New Yorkare insanely crowded. Still, they thrive and inspire, catalyze personal transformations and fuel creativity, not through wide-open spaces but through vibrant congestion.

Bombay (or Mumbai; locals use them interchangeably) reaches out into the Arabian Sea like an extended palm; and like veins traveling up the arm, its roads and subway lines run on a north-south axisakin to Manhattan’s, actually. The city is narrow, also like Manhattandivided by Mahim Creek into North and South Bombay (NoBo and SoBo). The neighborhoods are as evocative to Indians as those of that other island it vaguely resembles are to Americans, with edgy Colaba its TriBeCa; Nariman Point its Wall Street; the Gateway of India its welcoming arch and lookout point; all the way up to Bandra, as wholesome and hip as the Upper West Side; and the suburbs beyondGhatkopar, Malad, and Thane.

Bombay is India’s dream weaver, its cockaigne for consumers, its paean to possibilities. Here are the origins of five percent of the country’s GDP, forty percent of its income tax revenue, seventy percent of its capital transactions, one-third of its industrial output. It is the place where pretty young things get off the train with one suitcase and the phone number of a producer relative; where indigent street children dance salsa in the hope of getting onto a reality TV show; where the dhobiwho washes clothes for a living gazes at his client’s Mercedes with aspiration, not envy. Bombay is the rising spires of Nariman Point, to which bankers like my husband commute each workday to move millions, but it is also the stench and sewers of Dharavi, Asia’s second-largest slum, where Muslim tanners toil alongside Hindu potters. Bombay is where Mukesh Ambani, India’s richest man, is building a twenty-seven-floor home for a reported two billion dollars, with a staff of six hundred to serve his six family members. It is also the crowded by-lanes of Null and Chor bazaars, where artisans from Lucknow live and work in dark, dank rooms, embroidering stunning yellow butterflies that take flight on silk fabrics destined for Europe. Bombay is the city where the inchoate yearnings of a largely repressed nation burst forth into rapturous rainbow reality. For the destitute lad trapped in India’s hinterlands, Bombay could well be El Dorado. More than any other global citysave perhaps São PauloBombay is a study in contrasts, contrasts which keep getting starker.

“Bombay’s contrasts drive you crazy, but they are what make it the bustling metropolis that it is,” says Nikunj Jhaveri, forty-five, a lifelong Bombayite. “Bombay is like a rose. Roses come with thorns.”

A courteous bon vivant with an Italian belly laugh, Jhaveri is part of the swish SoBo set: incestuous, interwoven, and snobbish, more Upper East Side than India. If they don’t date each other or serve on the same boards, then their kids attend Cathedral School together (author and pundit Fareed Zakaria is an alum). “Townies,” they are called by the “Burbies” of NoBo.

Jhaveri was my husband’s classmate at IIT Bombay, India’s top engineering school. Although he comes from a prominent business familyhis brother deals diamonds out of New YorkJhaveri gave it all up to work for nonprofits and run an IT consultancy that takes him to Geneva and across the globe. But, he says, he is happiest in Bombay. When I ask if he would like to move to New York like his brother, he stares at me as if I am mad and asks, “Why?”

This is a pattern. Bombayites view their city with a pride and passion that can seem sickeningly insular to Indians from elsewhere. Pretty much everyone I meet says that he can’t imagine living anywhere elseafter, of course, heartily kvetching about Bombay. I mean, are they listening to themselves? I find this particularly galling because I now live in Bangalore, a city which knows that it is not the epicenter of anything. How about some humility here, I feel like telling the smug Bombayites. Humility, the great Indian virtue.

“Bombay has a zing to it. You clear your mind here. Maybe it is because of the sea,” says svelte Sangita Jindal, whose last name carries as much weight in India as Carnegie or Mellon would in the States; enough to get Al Gore to fly over for the launch of the children’s books she published on behalf of the JSW (Jindal Steel Works) Foundation.

“Why can’t Bombay have a summer festival like the one in Central Park?” demands Sanjna Kapoor, who runs Prithvi Theatre, founded by her English mother, Jennifer Kendal, and Bollywood actor father, Shashi Kapoor. “Bombay needs thirty Prithvis.”

“Bombay is both the New York and L.A. of India,” says industrialist Nadir Godrej as we share fresh lime soda at the posh Willingdon Sports Club (membership wait list: thirty-four years and counting). “It was oriented toward the West long before the rest of India was.”

“This city, she sucks you in like a whore, man,” announces a drunk as he rests on my shoulder. “So you never leave.”

“The amazing thing about Bombay is how you can cram so many people into such a small space and not have them continually kill one another,” says Nagesh Kukunoor, who quit an engineering career in Atlanta to make films in Bombay. “I mean, there is no shooting, slapping, or road rage.”

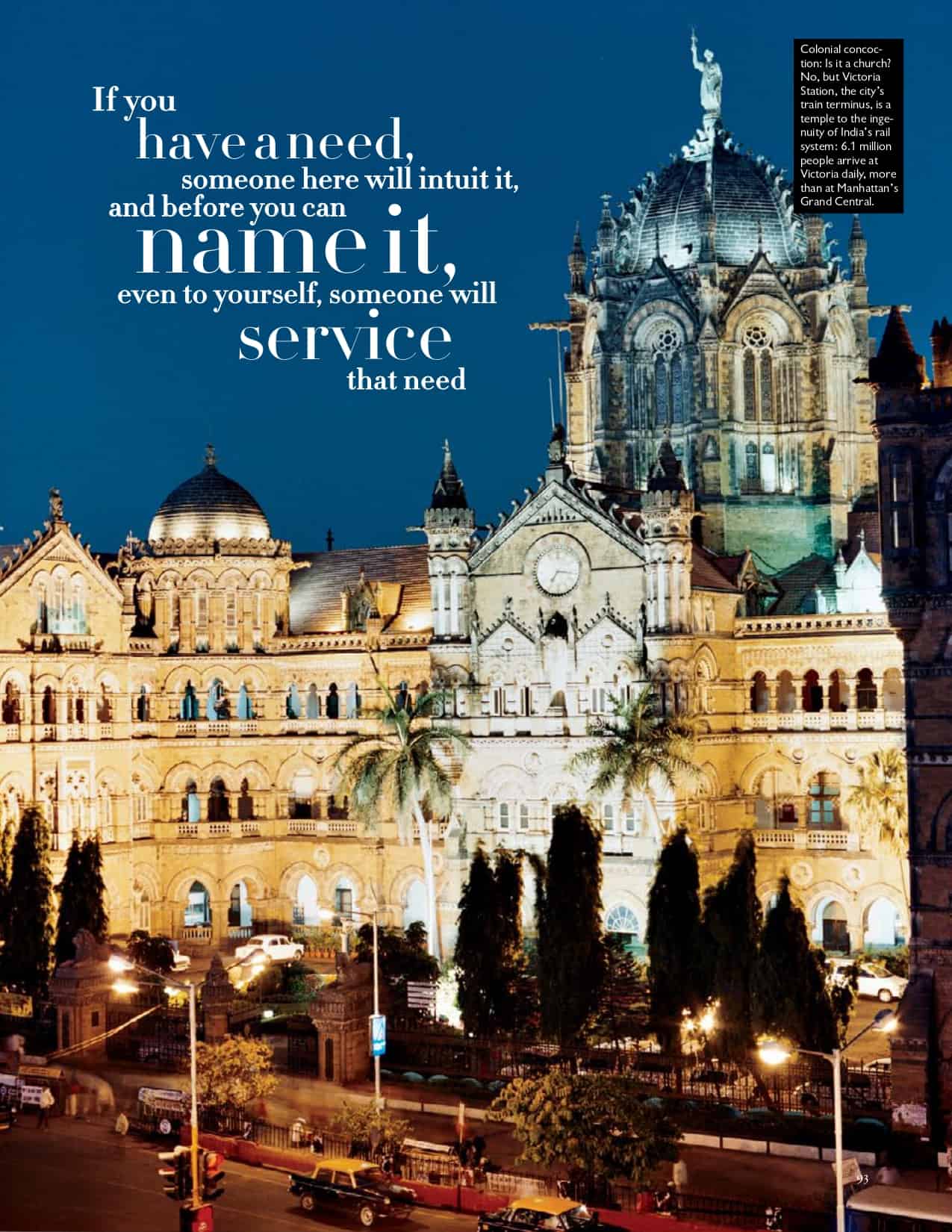

With eighteen million peoplegive or take a millionBombay is the most densely populated city on earth. And Kukunoor is largely right. For proof, I ride the Virar local one day. India has one of the biggest and busiest rail networks in the world, and it all began right here in Bombay in 1853.

Today, the city’s train system is as complex as New York’s except that each day it transports about a million more peopledreams and sweat intact. The trains aren’t for the faint of heart, but the ladies’ compartment is tolerable.

As the local leaves Virar, in the northern suburbs, early one morning, women congregate in small groups, dissing their mothers-in-law, singing bhajans, hemming saris, playing cards, and buying everything from bindis to beedis (a thin cigarette) from itinerant vendors. That evening, I watch a woman climb in at Byculla station laden with bags of fragrant farm-fresh vegetables that her cohorts fall on with cries of delight. Together, the women begin chopping beans, shelling peas, cleaning fish, and bagging everything so that by the time the train reaches Virar at 8:30 P.M., each woman has prepped her dinner and indulged in group therapy, leaving the compartment a mess of scales and shells.

But it is the dabbawalas, or lunch-box carriers, who are Bombay’s most famous train riders. Feted by Prince Charles and Richard Branson, studied by the Harvard Business School, and given a Six Sigma rating (one error in six million transactions) by Forbes Global, these five thousand men trawl the trains in trademark white kurtas and Nehru caps, schlepping some 200,000 lunch boxes to offices.

The concept is simple. Every morning, millions of commuters leave suburban homes at dawn to be in their offices downtown by 8 A.M. The dabbawalas show up two hours later, pick up boxes of home-cooked food, and deliver them to the offices.

They code the boxes so that the vegetarian Jain diamond merchant gets his non-garlic dal, the fish-loving Konkani trader his chili prawns, and the dieting Gujarati executive his steamed vegetables. Later, empty lunch boxes are collected from the offices and delivered back home. No modern technology, no computer spreadsheetsjust memorized codes and the muscles to fleet-foot coffin-sized trays containing multiple lunch boxes through the crowded chaos of Bombay’s streets. A sample code would be D9MC3, where D is Dadar station, the point of origin; 9 is Nariman Point, Bombay’s financial district; MC is Mafatlal Center; and 3 is the third floor. Beyond that, these paladins of piggybacking keep track of their lot of lunch boxes, perhaps through the scent of distinctly flavored masalas and curries.

It isn’t just food delivery that makes Bombay the epitome of economic ingenuity. After all, you can have toothpaste delivered in New York City. The difference is this: If you compliment a New York cabbie for his knowledge of the city’s streets, he’ll probably shrug it off. Cab drivers in Singapore or London might murmur politely that they’ve grown up in the city. A Bombay cabbie, however, will take your measure and ask as you get out, “Do you need a tour guide? I get off my shift at 4 P.M. and can show you the city. Only one thousand rupees for four hours.”

If you have a need, someone in Bombay will intuit it, and before you can name it, even to yourself, someone will service that need. That’s the difference.

I think of this as I enter Chowpatty Beach. There is something wonderfully egalitarian about the scene here. Bombay’s millionaires may have their exclusive high-rises along Marine Drive, but the sea is open to everyone. All of India is in evidence: burka-clad women helping kids build sand castles, Goan Christian couples strolling at the water’s edge, and large Hindu families sitting on the sand, sari-clad grandmothers munching peanuts alongside teenagers in halter tops.

This is the thing about Indiajust when you dismiss it for its many ills, it surprises you. For instance: The traffic, while chaotic, is an exercise in democracy. A bullock cart and bicycle have just as much right on Indian roads as a Mercedes-Benz, and indeed it is the Benz that is vulnerable to dents and scratches from passing cows. So while I sympathize with the ferengis, or foreigners, who complain about India’s choked roads, I think the trick is to view the whole thing as a circus, not a thoroughfare. Where else, after all, will you see a cow chomping on a billboard of a Bollywood vamp painted in lurid pink?

At Chowpatty Beach, smiling urchins carrying bamboo mats accost me. They offer to spread the mats on the grainy sand and bring me takeout from the nearby stalls. “Relax, madam,” they say. “Here menu.”

“These guys weren’t here a few years ago,” a friend tells me. “But they have figured out that people don’t like to stand in queues and pick up food, so they do it for them.”

Whether it is a one-dollar chaat (street snack) or a million-dollar transaction, when there is money to be made, Mumbaikars know how to make it.

The Bombay Stock Exchange (the oldest in Asia) invented the badla, which my financier husband tells me is “a homegrown over-the-counter carry-forward system”whatever that means. Matka gambling, a giant numbers-based lottery, possibly the largest in the world, originated in Mumbai. And even today, you can walk into a seedy lane within Chor (the word means “thieves”) Bazaar, hand over a suitcase full of rupees, and have forty thousand dollars delivered to your son in Michigan the next morning so that he can make his tuition payment. All the kid needs to do is say a code word to the guy who shows up at his doorstep the next morning. No records, no receipts; simply word of mouth and trust. That’s Bombay’s hawalasystem: illegal for sure, but Bombayites trust it more than Western Union. The city’s diamond merchants use angadias, or trusted couriers, who transport four to ten million dollars’ worth of cut and polished diamonds from Surat to Bombay. These angadias guarantee safe delivery of the diamonds for a salary of approximately a hundred dollars a month.

“You won’t go hungry in this city,” says Rajan, who drives me around from dawn to midnight. “As long as Maha Lakshmi [the Hindu goddess of wealth] is here, the money will come.”

Although I grew up in India, I never had the courage to approach Bombay. The city was as much a chimera to me as New York is to a kid in Salem, Indiana. It was too crowded, too fast, too big, too much. It took twenty years and a detour through the Bronx to give me the nerve to tackle Bombay.

In 1996, while I was away in America, the city shed its elegant colonial name for the earthier Mumbai. Locals use both according to whim and circumstance, calling it Mumbai at government offices and on commuter trains and Bombay at nightclubs and art openingsperhaps a city as many-splendored as this one deserves two names.

“Bombay or Mumbai, it is Urbs Primus Indis,” pronounces a bearded gent after a ponderous sip of sulaimani chai at the Prithvi Theatre café. “Res ipsa loquitor,” he adds. Unneccessarily, I think, since I don’t know its meaning.

The Prithvi Theatre’s café is where the city’s cognoscenti come to sip tea, write scripts, and, it seems, spout Latin. I’m there one evening to watch a play called Jazz. After the show, I steal away from my friends to chat up the spectacled chappie who has intellectual written all over his hand-loomed kurta. I expect profundity, even gravitas, but not the Latin. Typical Bombay show-off, I think sourly, as I retreat to my french fries. Res ipsa whatever indeed.

After I look up the meaning, I realize that the man’s comment underscored the way Mumbaikars view their city. Mumbai is the capital of the western Indian state of Maharashtra, yes, but like all great cities of the world, its identity is deeply individualistic and not entrenched in geography, religion, or indeed the state to which it is attached. What the Netherlands is to design, Los Angeles to fame, Dubai to money, and Kyoto to beauty, Bombay is to trade and opportunity. Everyone in this town has a gig. (One socialite, Chhaya Momaya, coaches rich businessmen’s wives in “controlling odors” and “rest room etiquette.”)

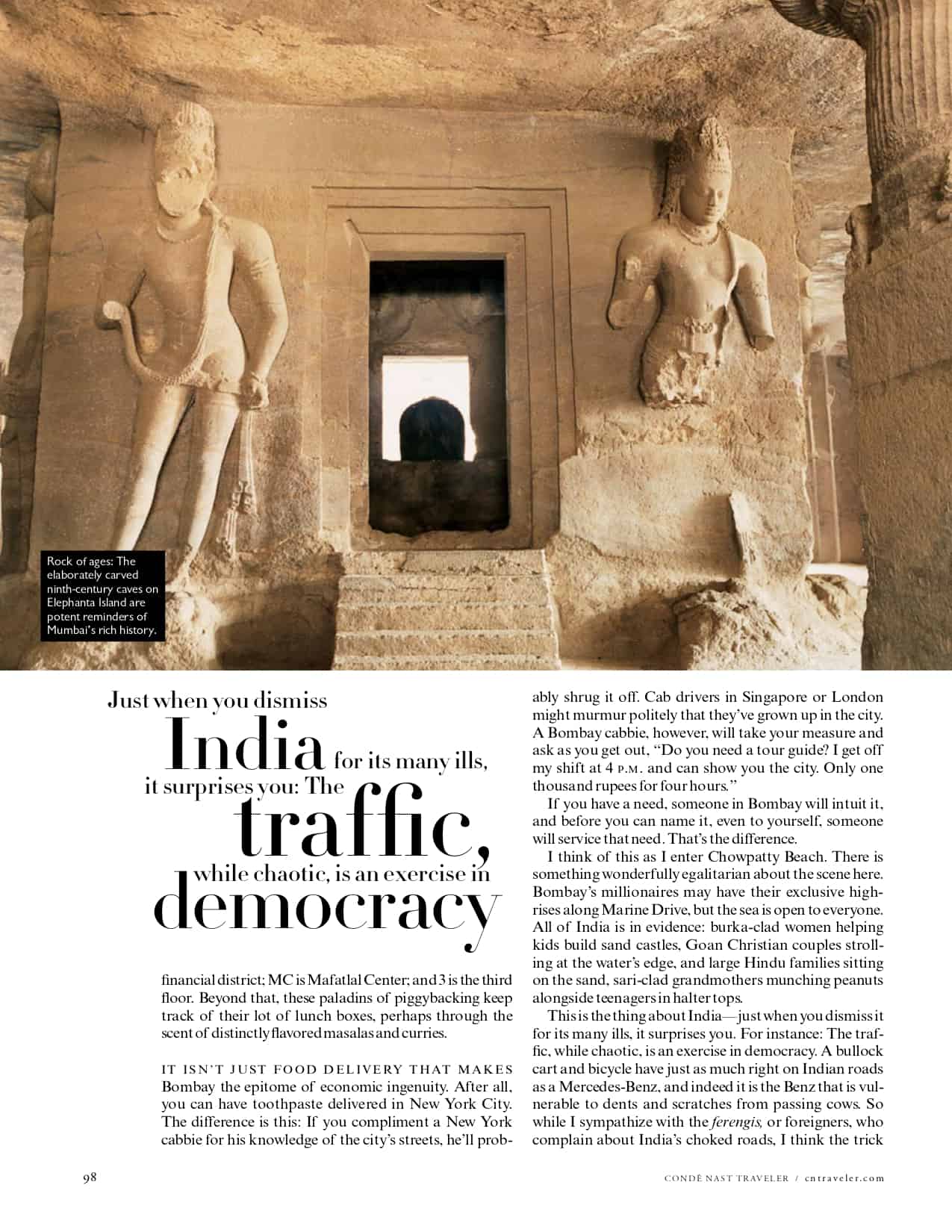

To escape the stultifying upper echelons of Bombay society, I take a boat trip to Elephanta Island and the magnificent temple complex. Built between the second century B.C. and the twelfth century A.D., it is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It’s blazing hot, and I have to climb some 120 steps to reach the entrance. Ahead of me in the queue are an Indian woman and her three British friends. It’s clear from her accent that she grew up in the United Kingdom. It’s also clear that she is going to fake being a native because the entrance fee is twenty rupees for Indians and two hundred rupees for foreigners. The man behind the counter sees right through her and charges her the foreigner price. Then comes my turn.

“One ticket,” I say.

“Indian or foreign?” barks the mustachioed man.

“Indian, of course,” I reply, feigning outrage.

“Where are you from?” he asks.

“Bangalore.”

“What’s your zip code?” he asks.

I don’t expect the question, and for the life of me, I can’t remember my zip code. Perhaps it is the heat; perhaps it’s the exertion of climbing a gazillion steps. I stare at him, wide-eyed.

“Look, madam, don’t try to fool me.”

“I am not,” I cry. “Here, you want to see my license?” I hand him my Karnataka state driver’s license.

“Twenty rupees.” He admits defeat.

As I wander through the beautiful caves, trying to take in the monolithic sculptures of Lord Shiva in the half-man, half-woman Ardhanari pose, I’m overcome with remorse. After all, I hold a U.S. passport and ought to pay foreign rates. The man was simply doing his job. He ought to be congratulated, not conned.

So I walk back to the counter and offer to pay the difference. The man gets suspicious. Why am I trying to pay more money? Am I from the income tax department? Am I offering a bribe? Am I a reporter with a hidden camera?

No bribe, no camera, I reply, exasperated. I am indeed from Bangalore, only by way of New York.

“Look, lady,” says the man, “I don’t care if you are from Bangalore or Bangladesh. I am not a Raj Thackeray to discriminate against people. You want to give me two hundred rupees. Then give, by all means.”

He pockets the cash and I walk away, perplexed over whether I’ve just done the right thing or I’ve just been had.

The man’s allusion was well put. Two years ago, the politician Raj Thackeray tried to polarize the city by pitting native Maharashtriansthe “sons of the soil,” who make up just over fifty percent of the populationagainst scores of migrant North Indians. The city didn’t bite. Sure, there were some skirmishes, but most Bombayites simply didn’t buy into the “us versus them” argument. That’s because Bombay is a city of immigrantsalways was, always will be.

The Koli fisherfolk came here first in 1138, in Arab dhows that they rowed across red sunsets to discover what the Greeks call Heptanesia, or Cluster of Seven Islands. The Kolis named the hilly uninhabited isles Mumba Ai after their patron goddess, Mumba Devi. Koli settlements still exist in Mumbai, right by the water. The men still fish; the women, pretty in green saris, take the fish to market.

The seven hilly isles were under the control of a series of Hindu rulers starting with Ashoka in the third century B.C. and ending in the fourteenth century with the Silhara dynasty, which made Elephanta Island its capital. At the same time, the Muslim kings of Gujarat captured Bombay. Arab spice traders visited and called one of the islands Al Omani, which the Brits corrupted into Old Woman’s Island.

In the second century, the Bene Israelis, descendants of the Jews who escaped persecution in Galilee, became shipwrecked off the coast of India and made their way to Bombay. The Baghdadi Jews followed. Although they forgot Hebrew and lost their religious books in transit, they maintained their dietary restrictions and kept the Sabbath, leading them to be called Shanivar Telis, or “Saturday oil-pressers.” Today, at least ten synagogues, including the beautiful blue 125-year-old Keneseth Eliyahoo Synagogue, exist in Bombay. Ehud Olmert and Madonna were recent visitors.

The Parsis, or Zoroastrians, who fled Muslim persecution in Persia in the tenth century, ended up in Bombay in the 1600s. For such a small community, they’ve made a global mark: Conductor Zubin Mehta is a Parsi from Bombay, as is his brother Zarin Mehta, the current director of the New York Philharmonic. So is Ratan Tata, who runs India’s largest private sector conglomerate, the Tata Group. So was the lead singer of the band Queen, Freddie Mercury, formerly known as Farrokh Bulsaraa Bombay boy.

The Parsis built ships, lent money, sold textiles, and traded opium, all of which were remarkably lucrative. Unlike the pre-colonial Hindus and Muslims, who considered themselves defiled if they shook hands with an Englishman, the Parsis had no such qualms. Like all comprador communities, they adapted names and customs that could be comprehended by the British. Typical Parsi names include their trade, as in Treasuryvala (vala means person), Icecreamvala, Canteenvala, and my personal favorite, which happens to be the name of a successful Bollywood film producer, Screwvalaas in Ronnie Screwvala.

Today, Bombay’s Parsi population is dwindling because intermarriage is discouraged. Parsi housing coloniescalled baugs (literally “gardens”)offer apartments to Parsis at subsidized rates, which, in land-starved Bombay, is always a source of envy and contention.

Most worrying of all, there are no vultures at the Towers of Silence. Parsis don’t bury or cremate their dead; instead, they offer the corpses for vultures to feed on, something that “probably made sense in the desert,” as Nadir Godrej tells me. Today, the Towers of Silence occupy fifty-five acres of prime property in the posh Malabar Hill district. The Parsis put their dead into special slots for men, women, and children in these towers and allow them to be consumed by the vulturesat least in theory. Other residents complain about rotting corpses.

“There are no vultures anymore,” says Homai Modi, a trustee of the KR Cama Oriental Institute, which preserves rare Zoroastrian and other manuscripts. “Solar concentrators [essentially a huge magnifying glass] have been installed, but they cannot function effectively during the monsoons. Several Parsis now go in for electric cremation, but most of the priests will not perform the usual prayers.”

A beautiful lady with translucent porcelain skin, Modi also heads the Maharashtra branch of the Indian Red Cross. She talks about Bombay’s resilience, its ability to recover after bomb blasts, floods, and Hindu-Muslim riots. Modi and her sister, Dr. Firoza Bhabha, are what we might call Good Samaritans. “Bombayites call us mad Parsis,” says Bhabha with a laugh. A slim, elegant lady with an easy smile, Bhabha is a successful pediatrician in Bombay. But her real passion is VOICE (Voluntary Organisation in Community Enterprise), a charity that educates Bombay’s street children and prepares them for independence and a livelihood. After the 2006 Bombay train bombings, Bhabha and her son, then a student in Boston, went to Sion Hospital, where the blast victims were brought, to volunteer. “They had no need for our help,” she says. “Everything was under control.” People had lined up to donate blood; the emergency room was functioning with seamless efficiency; dead bodies were classified and sent to the morgue; and the wounded were attended to right away. “That is the spirit of my city,” says Bhabha.

Bombay’s spirit of resilience is often a matter of pride for its natives. Yet after the terrorist attacks of November 26, 2008referred to locally as 26/11 in poignant allegiance to 9/11things were different. For the first time, Bombayites were angry. They wanted basic human rights: safety, protection. They wanted the city’s government to do its job.

A week after the attacks, a massive peace rally was held near the Gateway of India, and thanks to Twitter, Orkut, and Facebook, in cities across the globe as far away as Florida. But “the protests and text-message slacktivism. . . seem naive in their rejection of the political system,” wrote Naresh Fernandes, editor of Time Out Mumbai. Mumbaikars, he said, needed to “focus their outrage.” Still others simply wept. “My bleeding city. My poor great bleeding heart of a city. Why do they go after Mumbai?” asked Suketu Mehta, author of the masterful Maximum City, in a New York Times op-ed. “People use the spirit of Bombay as an excuse,” said a transplanted Bombayite at a candlelight vigil I attended in Bangalore. “Floods, bombs, corruption, terrorismthe city takes it all and rises from the ashes. Well, guess what. We’re done. We quit.”

The city did rise from the ashes, though. A few days after the attacks, even as the entire nation engaged in a collective, anguished soul-searching, Bombay picked itself up. The trains were running, the hospitals were humming, and the blood banks were, as usual, oversubscribed.

Bombay’s generosity in times of crisis is famous within India. The city comes together and pulls itself up, all the more heroic given its hands-off, even cold, attitude during normal times. “People here don’t care where you come from or what your social status is,” says Deepa Krishnan, a former banker who runs one of the city’s best tour companies, Mumbai Magic. “It is all about where you are going.”

One rainy June morning, everyone is going to Mahim’s St. Michael Church to see the bleeding Jesus. It is a bloody miracle, and everyone wants a look. People stream out of offices, cut college classes, and queue up outside the church to see a framed photograph of Jesus with a red patch on his chest.

I am the only voice of dissent. Couldn’t it be the moisture? I ask the crowd. Could the red paint of Jesus’ robes have bled and created that red patch? They glare coldly at me. Obviously I am new to Bombay, they say. This is a city of miracles. A few years ago, Ganesh, the Hindu elephant-god, began drinking milk. At temples all over Bombay, people would pour glasses of milk down the elephant-god’s mouth and the stone-idol would slurp it up. This happened for weeks before Lord Ganesh was satiated. Miracles happen all the time at the Haji Ali Dargah, one of the most famous mosques in the world. Now it’s Jesus’ turn. Nobody knows exactly why Jesus is bleeding, but whatever the reason, they are going to send a photograph to the Vatican for verification.

The residents of Dharavi, India’s largest slum, believe that Jesus is bleeding out of sympathy for their plight. Thanks to Bombay’s expansion northward, Dharavi, which once used to be on the city’s fringe, has now become metropolitan Mumbai’s geographic center. With its central location came the land sharks. A couple of years ago, Mukesh Mehta, an architect from America, announced his $3.1 billion Dharavi Redevelopment Project. According to his plan, 360 of Dharavi’s 557 acres would be parceled off to different real estate developers who could erect office buildings, luxury hotels, and mallson one condition: that they would have to house the million-odd slum dwellers who currently live and work in Dharavi. The residents were aghast. Dharavi is already the most densely populated place on the planet, nearly six times as dense as daytime Manhattan by some estimates. How can you bring more people into the place? The infrastructure would collapse. Indeed, it already has.

Dharavi may be a slum, but it is also a thriving economic zone. The Economist estimates the value of goodsleather handbags, embroidered clothes, potsmade in and sold from Dharavi every year at $500 million. “A lot of loading and unloading happens in Dharavi,” says Raju Korde, a social activist who opposes the plan. “It doesn’t account for the web of activities that we have here.” For now, the redevelopment proposal is stalled within the quagmire of Bombay’s bureaucracy, but for Dharavi’s residents, it represents an uncertain futureand the growing schism between the haves and the have-nots.

For many in the West, their introduction to Dharavi came in the form of Slumdog Millionaire. Last year’s Oscar winner for best picture was partially shot in Dharavi and transformed two of its residentsnine-year-old Rubina Ali and ten-year-old Azharuddin Mohammed Ismailinto international film stars. Months after the two returned from the Oscars, an English newspaper reported that Rubina’s father was trying to sell her to Arab sheikhs for more than $300,000, a story the father adamantly denied. Both stars continue to live in Dharavi with their large families.

Dharavi’s other residents, meanwhile, complain that Slumdog Millionaire has done little to help them. “I may live in a slum, but I am no dog,” a little girl complained in an interview. Others said that their lives were exactly as the film portrayed, while newspaper editorials opined that the film glorifies poverty. But one thing is certain: It will not be the last take on Mumbai, not least of all from the film’s director, Danny Boyle, who is said to have bought the rights to Mehta’s Maximum City as a future project.

Within India, Mumbaiya English is known for its swagger: part Brooklyn with the hip-hop beat of the Bronx, plus some Hindi words thrown in for good measure. A typical Bombay greeting is bhol, or talk. Every sentence ends with yaar, which means friend but has now become a verbal tic like dude, as in, “No, yaar. Can’t party tonight.” Ask a friend about his latest quarrel with his girlfriend and you will be met with a taciturn, “Avoid, yaar,” or “I don’t wanna talk about it.” Women are babes, men are dudes, and everyone is irreverent.

Bombay’s colonial history is best told in the spangled argot of its natives. With advance apologies to all the Mumbaikars who will poke holes in it, here is my attempt.

So there was this babe, Catherine de Braganza. A Portuguese princess with a beaky nose. Roman Catholic. Her parents tried to marry her off to pretty much every royal in Europe before foisting her onto England’s Charles the Second. Charles was broke and wanted Lady Catarina’s dowry: six shiploads of gold plus the port cities of Tangier and Bombay. The Portuguese thought they were suckering the Brits, you see. Tangier amounted to nothing in 1661; Bombay at that time had less than ten thousand people. The Portuguese didn’t want it.

So anyway, the British crown got the biggest lollipop of the century, and they didn’t know what to do with it. So the bozos leased it to the East India Company for a measly ten pounds a year. The East India Company realized right away that Bombay had this great inland harbor, which protected its ships from Arab pirates. So it moved all its shipbuilding operations from Surat, in Gujarat, to Bombay.

Now this guy, Gerald Aungier, was the second governor of Bombay. He went around inviting everyone to move to Bombay. “I’ll guarantee your safety,” he said, “and give you religious freedom. Let’s grow fat and happy together.” So they camethe Bohra Muslims, the Catholic Goans, the Gujaratis, the Marwaris from Rajasthan, the Sindhis, the Jews, and the Parsis. Anyone who wanted to make a buck made his way to Bombay.

The Jews and Parsis hated each other because they competed for the same businesses: shipbuilding, textiles, and opium. They competed with each other in the Good Samaritan area, too. These Parsis really are mad. Much of Bombay University was built by a Parsi: one Cowasjee Jehangir, who made so much money that the family called itself Readymoney. (I am not making this up. Wiki it if you like.)

The other guy with a funny name is Benjamin Horniman, and man, was he horny! (Sorry, couldn’t resist.) Horniman was Irish and supposedly gay. Being Irish and all, he supported the Indians against the Brits. After independence, the government honored him by changing Elphinstone Circle into Horniman Circle, which is what it is called to this day. Prithvi Theatre stages plays there during the summer.

Mountstuart Elphinstone himself was no slouch. He was president of the Asiatic Society of Bombay, whose library has one of the two known original manuscripts of Dante’s Divine Comedy. In fact, in 1930 Mussolini offered the library a million pounds for one of them, but the society refused. I don’t know why they would turn down a stash of cash for some ancient crap, but there it is: Dante’s Divine Comedy. It’s still at the Asiatic Society library, and you can get special permission to see it.

The city’s big leap forward came during the American Civil War, when cotton exports from the American South dropped. Bombay took over and became a great cotton-trading center. Then the Suez Canal opened and the whole thing got more intense. Huge cotton mills sprung up; tons of migrant laborers came to work. They stayed at the Bombay _chawls_basically dorm-style housing with one toilet. You still see them all over the place. The mill workers lived in the chawls and partied at night. They did street theaterpolitical satires, mythological extravaganzas, you name it. That’s why Bombay has such a strong regional theater tradition. Nowadays, most of the huge cotton mills are being converted intoget thisnightclubs and shopping centers. The Mathuradas Mills compound is now the Blue Frog nightclub. Phoenix Mills is now a mall. Weird, isn’t it?

It was only after the First War of Indian Independence, in 1857, that the British crown finally took over Bombay from the East India Company. In fact, the Gateway of India was built to welcome King George V and Queen Mary into India. The crown entered through the Gateway, and the last British troops left through the Gateway. Or so we Bombayites like to say.

So now we are in the 1940s and the freedom struggle is in full swing. In fact, Mahatma Gandhi launched the Quit India Movement from Bombay. He lived in Mani Bhavan, a building on Laburnum Road, for many years. You should visit it; today it’s a Gandhi museum.

In the seventies, Bombay had this massive land reclamation drive. Much of Marine Drive is built over “land that has been reclaimed from the sea,” as the books say. Today, of course, the big controversy is what to do with Dharavi. These real estate guys are real snakes, you know. They wanted to tear down the 138-year-old Crawford Market, but thankfully we all did morcha (protests) and got the thing stopped. You can’t fool us Mumbaikars.

That’s it, yaar. Bombay’s history as told by a Mumbaikar. Now let’s go grab a beer.

I have to admit that I still don’t really get Bombay. I can feel its exuberant energy, hear its passion, and see the panache of its citizens. Bombay may not cushion the fall of the average barber who wants to pole-vault across the class and caste hierarchies that define India, but it certainly will drive him to succeed. But is it one of the great global cities of the world, or is it merely, as a Kiwi tourist put it to me, “a shole”? Despite my days traipsing around the island, the city ultimately eludes my grasp. Just when I think I have it figured out, I see something that turns my theories on their head. In that sense, Bombay is like Chopin’s music: It shows but doesn’t reveal; it remains, ultimately, unknowable.

On my last day, I awake at dawn and go for a jog down Marine Drive. The monsoon has arrived right on schedule in early July. Sheets of rain sluice down my body as I run, the sea on one side and the Art Deco buildings on the other.

The night before, I dined with my cousin and his eighteen-year-old daughter, Sanjana. They live in Navi Mumbai, or New Bombay, which is arguably the largest planned township in the world, a parallel galaxy.

It was 11 P.M. and Spaghetti Kitchen, at Phoenix Mills mall (poised between South Bombay, where I was staying, and distant New Bombay), was bustling. Sanjana radiates the giddy enthusiasm of youth. She has six tattoos and multiple piercings. We are Brahmins, my family, yet Sanjana eats rare beef and speaks in unprintables. I gaped at this young lady who shares my family tree yet seems so different from me, as much a gypsy as I am a schoolgirl.

When Sanjana heard that I was writing about Bombay, she could not stop raving. Which other Indian city would accept a young girl with multiple tattoos? she demanded. In Bombay, she could come home at 2 A.M. and still be safe. She could lead her life and not be judged. Bombay wasn’t conservative Chennai or sleepy Bangalore; it wasn’t flashy Delhi or intellectual Calcutta. It was all of the above yet none of the above. Res ipsa loquitor. Not again, I thought.

I invited Sanjana to Bangalore. I would find her a job, I said. What I didn’t say was that I thought Bangalore would straighten her out, make her normal again. What was so great about Bombay? I demanded.

Sanjana stared at me. In a demure, respectful voice that would surely have made her father proudthat was in contrast to the braggadocio beat of Bombayshe replied, “Shoba-aunty, if you have to ask, you just won’t get it.”

I think about this as I pause at Worli Sea Face, out of breath, to stare at the raging gray water. Behind me, a small crowd has gathered to gawk at this woman standing in the rain in a clinging wet T-shirt. I catch snippets of the conversation. “Kya shooting chal raha he?” I hear a man ask. Is this a film shoot? Heroines clad in wet saris and dancing in the rain are a Bollywood staple, and he thinks I’m one. In this moment, I too live my Bombay dream. The city delivers. I run on.

Mumbai: Where to Stay, Eat, and Play

Mumbai is an easy city to get lost in, though goodness knows there are guides aplenty. Most hotels rent chauffeured cars ($30 per day), or you can just hail a taxi: My female Mumbai friends routinely take cabs even late at night. Trains are for the truly adventurous or the foolhardy, but as experiences go, they’re hard to beat. A former banker now with Mumbai Magic, Deepa Krishnan leads extremely informative customized tours (98-6770-7414; from $31). Less irreverent tours are given by Bombay Heritage Walks. Of particular note is the two-hour “Bombay Gothic’ architecture jaunt (22-2369-0992; from $10 per person). Finally, for a visit to the Dharavi slums, contact Reality Tours & Travels (98-2082-2253; from $10). For more on this tour, visit cntraveler.com to read News Editor Kevin Doyle’s account of his trip into Dharavi.

The country code for India is 91. Prices quoted are for October 2009.

Lodging

The granddaddy of them all, the **Taj Mahal Palace & Tower was commissioned by industrialist Jamsetji Tata in the early 1900s when he was allegedly refused entrance into the now-defunct whites-only Watson’s Hotel. The flagship property of the Taj group, it is architecturally stunning, with Belgian chandeliers and Goan artifacts. The Taj began reconstruction work directly after last November’s bombings; most of its rooms, restaurants, and suites will reopen this December. The renovation will be complete in March 2010 (22-6665-3366; doubles, $226$466). The ** ITC Grand Central’s midtown location makes it a favorite of visiting sports teams and therefore of gawkers. Its female-only floor, Eva, has a great selection of toiletries from Forest Essentials, a local brand (22-2410-1010; doubles, $490$656).

In Juhu, balding Bollywood producers, aspiring starlets, and socialites do deals at the glitzy JW Marriott. The rooms are small, but the infinity pool has nice sunset views (22-6693-3000; doubles, $187$343). With great vistas of the Arabian Sea and the lights of Marine Drive, **The Oberoi**which, like the Taj, is also undergoing serious renovationsis a good choice for Nariman Point financiers. There’s no date for its reopening yet, but when it does, check out the Tiffin Room; it’s the place for power breakfasts (22-6632-5757). The InterContinental Marine Drive is a small highdesign hotel with a great rooftop bar called Dome. Extras include a free welcome massage and free brownies (22-3987-9999; doubles, $298$525). The posh Grand Hyatt houses wonderful contemporary Indian art and a good restaurant, China House (22-6676-1234; doubles, $184$398; entrées, $14$35). The eco-conscious should head to the Orchid, which combines luxury with genuine green credentials (22-616-4040; doubles, $370). Finally, the new Four Seasons has superb service and comfortable if cozy rooms. The two inhouse restaurants are worth a visit (22-2481-8000; doubles, $276$419; entrées, $12$33).

Dining

For a true Bombay experience, go to Swati Snacks in the Tardeo District, where multiple generations wait in line to chow down on vegetarian Gujarati snacks and dishes (248 Karai Estate; 22-6580-8406; entrées, $2$8). Trek to Khotachiwadi for Maharashtrian food at Anant Ashram , but note that there is no English menu and cameras bring a bouncer (46 Khotachiwadi, Girgaon District; no phone; entrées, $1$3). A more upmarket, airconditioned option is Sindhudurg (Sita Building, Dadar West; 22-2430-1610; entrées, $3$8).

Many places serve coastal seafood, of course. Trishna gets the most press, but locals regard it as a tourist trap (7 Shri Sai Baba St., Parel District; 22-2270-3213; entrées, $10$51). Good alternates include: ** Mahesh Lunch Home** for tandoori crabs and stuffed pomfret (8B Cawasji Patel St., Fort District; 22-2287-0938; entrées, $4$37), Excellensea (317 Bharat House, S. Bhagat Singh St.; 22-2261-8991; entrées, $10$15), or its lowerpriced spinoff at the same address, **Bharat Lunch Home **(22-2267-2677; entrées, $2$4).

At ** Golden Star Thali**, nimble waiters pile on the delicious vegetarian dishes until you cover your plate with both hands (330 Raja Ram Mohan Roy Rd., Girgaon District; 22-2363-1983; meals, $10).

Indigo serves Continental food in a casual-chic atmosphere (4 Mandlik Rd., Colaba District; 22-6636-8999; entrées, $11$40), and its sister outfit, the ** Indigo Deli**, has great light lunches and fancy dinners (5 Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharishi Rd., Apollo Bunder District; 22-6655-1010; entrées, $7$9). The Olive Bar & Kitchen is a local favorite for Mediterranean food (14 Union Park, Pali Hill District; 22-2605-8228; entrées, $8$27).

Blue FrogZenziPoison****Not Just Jazz by the Bay

Reading

Bombay has inspired a surfeit of great Indian books, from Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children(Random House, $16) to Suketu Mehta’s Maximum City (Vintage, $17). Sharada Dwivedi and Rahul Mehrotra have coauthored several exhaustive but readable histories of the city, the best of which is Bombay: The Cities Within (out of print). Lastly, I found the snappily written Time Out Mumbai & Goa

Leave A Comment