I am going to let you in on a little secret. I don’t know if it is the same in north India, but here in Chennai, where I grew up, everyone has this fixation that revolves around Bharatanatyam dancers. If you have a daughter, you want her to learn this ancient art form that originated with the sage Bharata and his text, the Natya Shastra. If you have a son, you want him to marry a Bharatanatyam dancer: she with the big, expressive eyes; slender fingers like okra (okay, it sounds better in Tamil, and perhaps that is why this particular vegetable is called lady finger); and a curvaceous figure that looks like it has sprung out of the Thanjavur temples. It is—if you’ll permit the expression—a collective Chennai wet dream, and it centres around one art form: Bharatanatyam.

Like all Chennai girls, I learnt Bharatanatyam as a child, thanks mostly to a family feud. My aunt is the legendary Bharatanatyam dancer, Padma Bhushan Kamala, who made her name as a child prodigy called “Kumari Kamala”. Her videos are still available on YouTube, uploaded by worshipful fans.

Kamala mami, as I called her, lived in Poes Garden, a stone’s throw away from chief minister J. Jayalalithaa’s home in Chennai, and performed at The Music Academy, while my cousins and I ran amok through her green room. My mother, naturally, wanted me to learn dance from her famous sister-in-law, but Kamala mami told my Mom that I wasn’t ready for dance. I was too young, she said. Too tomboyish was the unstated implication.

My best friend’s sisters, meanwhile, were learning from my aunt. They were beautiful twin girls, Ramaa and Uma, who later married and moved to the US. Ramaa Bharadvaj returned to India last year and is the dance director of the Chinmaya Naada Bindu academy in Pune. Watch her Jwala-Flame dance on YouTube. She performs it with her daughter, Swetha, and it is, in my mind, an amazing if non-traditional interpretation of Bharatanatyam.

At Women’s Christian College, Chennai, I spent three years with Urmila Sathyanarayanan, who would become one of the top Bharatanatyam dancers in the country. She was learning dance when we were in college, but had not become the sensation she is now. Urmila was riveting, even as a psychology student clad in simple cotton salwar-kameezes, playing truant from Mrs Koshy’s classes and getting roundly scolded for it. Her abhinaya, or expression, was in evidence then as it is now. Urmila has a mobile expressive face that grabs your eyeballs and doesn’t let go.

Although I have watched all the big dancers of today—Padma Subrahmanyam, Alarmel Valli, Malavika Sarukkai, Shobana, Anita Ratnam and even abhinaya queen Guru Kalanidhi Narayanan, who can emote the navarasas like none other—I haven’t yet been able to watch Priyadarsini Govind perform, something that I will rectify soon by attending her performance at The Music Academy on 3 January. Govind is a dancer at the pinnacle of her prowess. Her adavus, or steps, are precise and symmetrical. Her abhinaya, or expressions, are perfectly adequate, if dispassionate. They don’t sweep you off your feet like Ms Narayanan’s did (it is hard for me to follow Mint’s journalistic code of “last names only, no titles”, when talking about these dancers whom I revere). As a girl, my mother took me to Ms Narayanan too.

Why hasn’t Bharatanatyam flourished as much as Carnatic music? There are more musicians than dancers; and more weeks dedicated to music than dance during the December season. It doesn’t make sense because dance combines music and performance. It gives you more bang for the buck, to put it in crude economic terms. Yet dancers occupy a smaller space than musicians in the cultural landscape, even in Chennai. Why? Is it because dancers are mostly women and they quit to raise children? Then again, most of the top Carnatic music singers are women too—Sudha Ragunathan, Ranjani-Gayatri, S. Sowmya, Bombay Jayashri and Aruna Sairam. They’ve managed to stay on top even after they become mothers and grandmothers. Is it because dance is more expensive and therefore does not attract more students, what with the spending on costumes and accompanying singers? I don’t know.

Shoba Narayan is a failed Bharatanatyam dancer. Write to her at [email protected]

- Columns

- Posted: Fri, Dec 30 2011. 9:58 PM IST

The Good Life | Shoba Narayan

I am going to let you in on a little secret. I don’t know if it is the same in north India, but here in Chennai, where I grew up, everyone has this fixation that revolves around Bharatanatyam dancers. If you have a daughter, you want her to learn this ancient art form that originated with the sage Bharata and his text, the Natya Shastra. If you have a son, you want him to marry a Bharatanatyam dancer: she with the big, expressive eyes; slender fingers like okra (okay, it sounds better in Tamil, and perhaps that is why this particular vegetable is called lady finger); and a curvaceous figure that looks like it has sprung out of the Thanjavur temples. It is—if you’ll permit the expression—a collective Chennai wet dream, and it centres around one art form: Bharatanatyam.

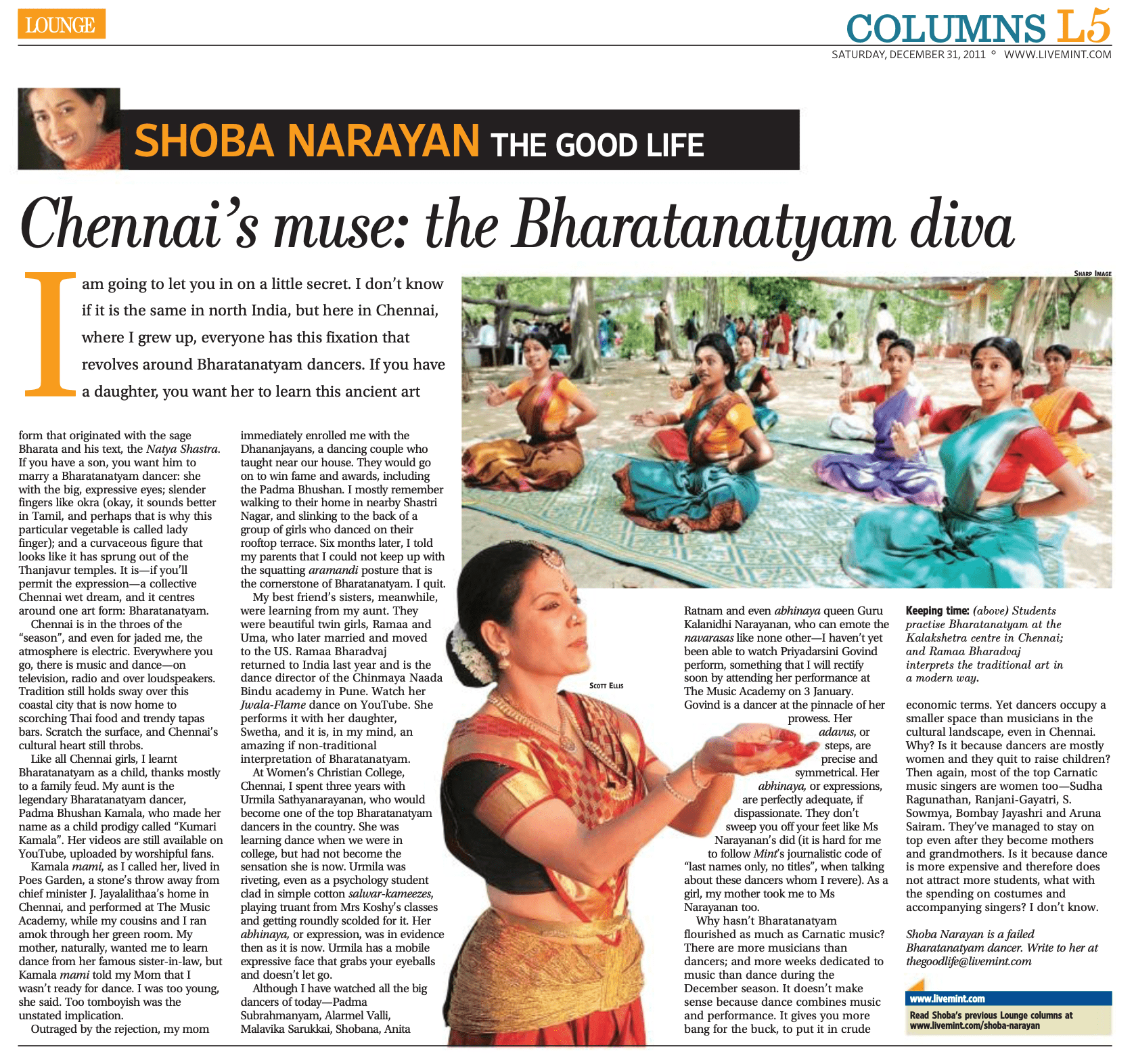

I am going to let you in on a little secret. I don’t know if it is the same in north India, but here in Chennai, where I grew up, everyone has this fixation that revolves around Bharatanatyam dancers. If you have a daughter, you want her to learn this ancient art form that originated with the sage Bharata and his text, the Natya Shastra. If you have a son, you want him to marry a Bharatanatyam dancer: she with the big, expressive eyes; slender fingers like okra (okay, it sounds better in Tamil, and perhaps that is why this particular vegetable is called lady finger); and a curvaceous figure that looks like it has sprung out of the Thanjavur temples. It is—if you’ll permit the expression—a collective Chennai wet dream, and it centres around one art form: Bharatanatyam.Keeping time: Students practise Bharatanatyam at the Kalakshetra centre in Chennai. Photo: Sharp Image

Chennai is in the throes of the “season”, and even for jaded me, the atmosphere is electric. Everywhere you go, there is music and dance—on television, radio and over loudspeakers. Tradition still holds sway over this coastal city that is now home to scorching Thai food and trendy tapas bars. Scratch the surface, and Chennai’s cultural heart still throbs.

Like all Chennai girls, I learnt Bharatanatyam as a child, thanks mostly to a family feud. My aunt is the legendary Bharatanatyam dancer, Padma Bhushan Kamala, who made her name as a child prodigy called “Kumari Kamala”. Her videos are still available on YouTube, uploaded by worshipful fans.

Kamala mami, as I called her, lived in Poes Garden, a stone’s throw away from chief minister J. Jayalalithaa’s home in Chennai, and performed at The Music Academy, while my cousins and I ran amok through her green room. My mother, naturally, wanted me to learn dance from her famous sister-in-law, but Kamala mami told my Mom that I wasn’t ready for dance. I was too young, she said. Too tomboyish was the unstated implication.

Ramaa Bharadvaj interprets the traditional art in a modern way. Photo: Scott Ellis

Outraged by the rejection, my mom immediately enrolled me with the Dhananjayans, a dancing couple who taught near our house. They would go on to win fame and awards, including the Padma Bhushan. I mostly remember walking to their home in nearby Shastri Nagar, and slinking to the back of a group of girls who danced on their rooftop terrace. Six months later, I told my parents that I could not keep up with the squatting aramandi posture that is the cornerstone of Bharatanatyam. I quit.

My best friend’s sisters, meanwhile, were learning from my aunt. They were beautiful twin girls, Ramaa and Uma, who later married and moved to the US. Ramaa Bharadvaj returned to India last year and is the dance director of the Chinmaya Naada Bindu academy in Pune. Watch her Jwala-Flame dance on YouTube. She performs it with her daughter, Swetha, and it is, in my mind, an amazing if non-traditional interpretation of Bharatanatyam.

At Women’s Christian College, Chennai, I spent three years with Urmila Sathyanarayanan, who would become one of the top Bharatanatyam dancers in the country. She was learning dance when we were in college, but had not become the sensation she is now. Urmila was riveting, even as a psychology student clad in simple cotton salwar-kameezes, playing truant from Mrs Koshy’s classes and getting roundly scolded for it. Her abhinaya, or expression, was in evidence then as it is now. Urmila has a mobile expressive face that grabs your eyeballs and doesn’t let go.

Although I have watched all the big dancers of today—Padma Subrahmanyam, Alarmel Valli, Malavika Sarukkai, Shobana, Anita Ratnam and even abhinaya queen Guru Kalanidhi Narayanan, who can emote the navarasas like none other—I haven’t yet been able to watch Priyadarsini Govind perform, something that I will rectify soon by attending her performance at The Music Academy on 3 January. Govind is a dancer at the pinnacle of her prowess. Her adavus, or steps, are precise and symmetrical. Her abhinaya, or expressions, are perfectly adequate, if dispassionate. They don’t sweep you off your feet like Ms Narayanan’s did (it is hard for me to follow Mint’s journalistic code of “last names only, no titles”, when talking about these dancers whom I revere). As a girl, my mother took me to Ms Narayanan too.

Why hasn’t Bharatanatyam flourished as much as Carnatic music? There are more musicians than dancers; and more weeks dedicated to music than dance during the December season. It doesn’t make sense because dance combines music and performance. It gives you more bang for the buck, to put it in crude economic terms. Yet dancers occupy a smaller space than musicians in the cultural landscape, even in Chennai. Why? Is it because dancers are mostly women and they quit to raise children? Then again, most of the top Carnatic music singers are women too—Sudha Ragunathan, Ranjani-Gayatri, S. Sowmya, Bombay Jayashri and Aruna Sairam. They’ve managed to stay on top even after they become mothers and grandmothers. Is it because dance is more expensive and therefore does not attract more students, what with the spending on costumes and accompanying singers? I don’t know.

Shoba Narayan is a failed Bharatanatyam dancer. Write to her at [email protected]

Leave A Comment