Clad in a khadi kurta-pyjama and Ferragamo flats, Sabyasachi Mukherjee, 37, is having lunch at the ITC Sonar, Kolkata. It is 4pm. We are at the coffee shop. He orders lal maas. I have already eaten. I order jhalmuri.

Mukherjee is also a “biryani freak” and will only buy it at Rahmania or Nizam’s for their “sinfully greasy biryanis”. Fish, he says, has to be eaten at home. He tastes myjhalmuri and finds, to his surprise, that it is “fantastic”. I bite into gravel while chewing. Perhaps, the hotel buys the dish from the street and sells it to its patrons. We order two more portions.

Started with a Rs. 20,000 loan he took from his sister, Payal, in 2002, Sabyasachi, the label, has grown into a behemoth, employing over 600 craftspeople, 32 assistants, including one from Harvard, and revenue topping Rs. 52 crore in 2011. Part of the reason is Mukherjee’s talent, but a bigger reason is his shrewd business acumen that allows him to spin fantasies out of this City of Joy.

“I am not India’s most talented or creative designer. But I am India’s most influential and powerful commercial designer,” he says matter-of-factly. There is context, of course. I asked him to rate himself. The man doesn’t go around making such pronouncements. Yet his smugness is galling.

I stare at him from across the table. With his long, wavy hair, Cheshire cat smile, and well-argued opinions, Mukherjee is hardly the angst-ridden, self-destructive designer along the lines of John Galliano or Alexander McQueen. Though perfectly courteous, he doesn’t pander or charm. He doesn’t seek to be liked and, frankly, is a bit too “sorted” for me. But after two days in his company, I end up with grudging respect for his fashion sensibilities. I like his reverence for textiles, his love of artisanal craftsmanship, his pride in being Indian, and the fact that he knows his mind and isn’t afraid to speak it. He slams the Hermès sari, waxes eloquent about the Dabu mud-resist hand-block print techniques of Rajasthan, and bemoans the fact that Indians don’t embrace native handmade traditions with the fervour that they do foreign brands.

“In airports, sometimes I will see African women dressed in their traditional garb—turbans and robes. I know that they will be travelling first-class because they have that confidence,” he says. “Why can’t we Indians take pride in our native clothes?”

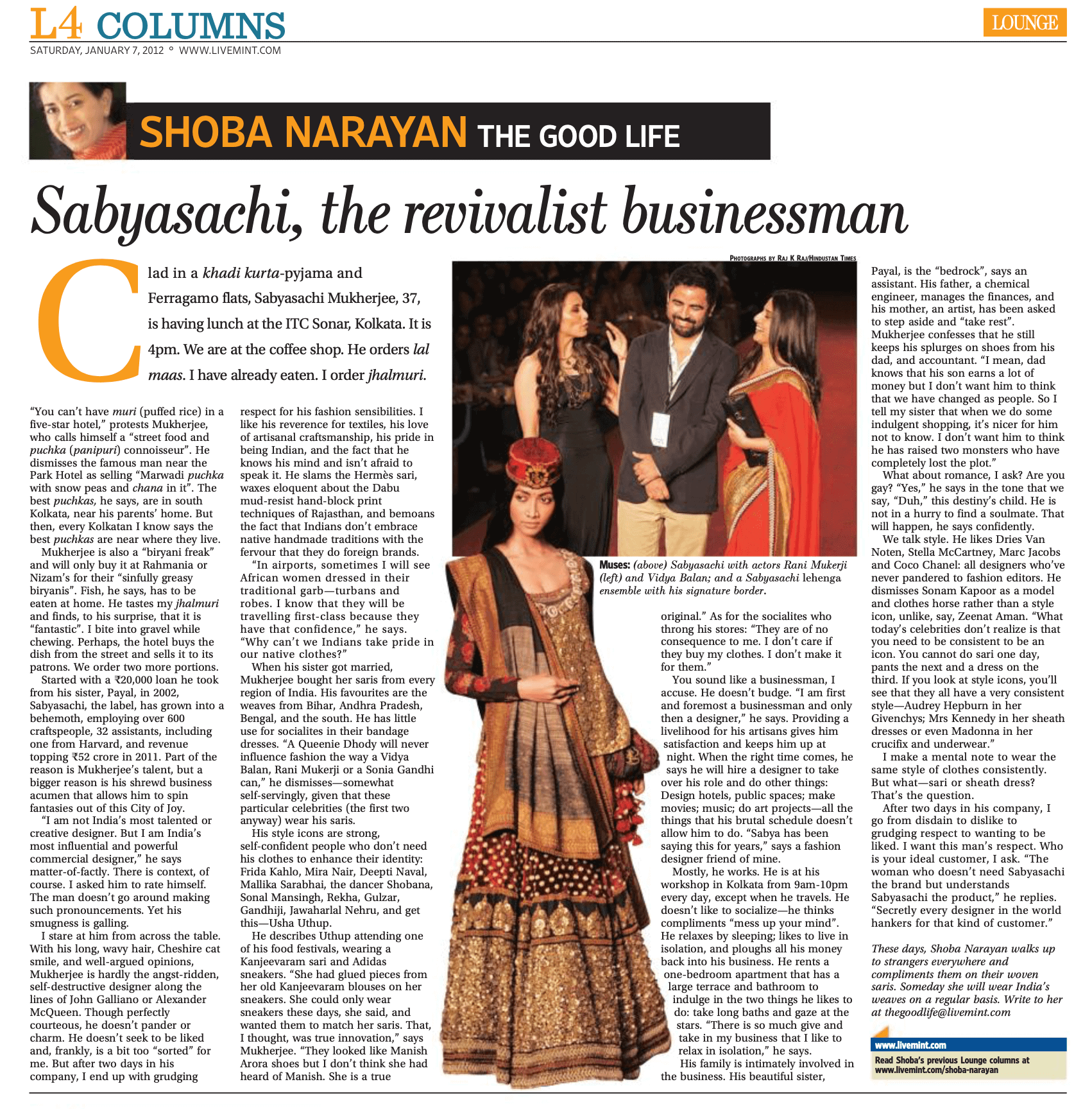

When his sister got married, Mukherjee bought her saris from every region of India. His favourites are the weaves from Bihar, Andhra Pradesh, Bengal, and the south. He has little use for socialites in their bandage dresses. “A Queenie Dhody will never influence fashion the way a Vidya Balan, Rani Mukerji or a Sonia Gandhi can,” he dismisses—somewhat self-servingly, given that these particular celebrities (the first two anyway) wear his saris.

His style icons are strong, self-confident people who don’t need his clothes to enhance their identity: Frida Kahlo, Mira Nair, Deepti Naval,Mallika Sarabhai, the dancer Shobana, Sonal Mansingh, Rekha, Gulzar, Gandhiji, Jawaharlal Nehru, and get this—Usha Uthup.

He describes Uthup attending one of his food festivals, wearing a Kanjeevaram sari and Adidas sneakers. “She had glued pieces from her old Kanjeevaram blouses on her sneakers. She could only wear sneakers these days, she said, and wanted them to match her saris. That, I thought, was true innovation,” says Mukherjee. “They looked like Manish Arora shoes but I don’t think she had heard of Manish. She is a true original.” As for the socialites who throng his stores: “They are of no consequence to me. I don’t care if they buy my clothes. I don’t make it for them.”

You sound like a businessman, I accuse. He doesn’t budge. “I am first and foremost a businessman and only then a designer,” he says. Providing a livelihood for his artisans gives him satisfaction and keeps him up at night. When the right time comes, he says he will hire a designer to take over his role and do other things: Design hotels, public spaces; make movies; music; do art projects—all the things that his brutal schedule doesn’t allow him to do. “Sabya has been saying this for years,” says a fashion designer friend of mine.

Mostly, he works. He is at his workshop in Kolkata from 9am-10pm every day, except when he travels. He doesn’t like to socialize—he thinks compliments “mess up your mind”. He relaxes by sleeping; likes to live in isolation, and ploughs all his money back into his business. He rents a one-bedroom apartment that has a large terrace and bathroom to indulge in the two things he likes to do: take long baths and gaze at the stars. “There is so much give and take in my business that I like to relax in isolation,” he says.

His family is intimately involved in the business. His beautiful sister, Payal, is the “bedrock”, says an assistant. His father, a chemical engineer, manages the finances, and his mother, an artist, has been asked to step aside and “take rest”. Mukherjee confesses that he still keeps his splurges on shoes from his dad, and accountant. “I mean, dad knows that his son earns a lot of money but I don’t want him to think that we have changed as people. So I tell my sister that when we do some indulgent shopping, it’s nicer for him not to know. I don’t want him to think he has raised two monsters who have completely lost the plot.”

What about romance, I ask? Are you gay? “Yes,” he says in the tone that we say, “Duh,” this destiny’s child. He is not in a hurry to find a soulmate. That will happen, he says confidently.

We talk style. He likes Dries Van Noten, Stella McCartney, Marc Jacobs and Coco Chanel: all designers who’ve never pandered to fashion editors. He dismisses Sonam Kapoor as a model and clothes horse rather than a style icon, unlike, say, Zeenat Aman. “What today’s celebrities don’t realize is that you need to be consistent to be an icon. You cannot do sari one day, pants the next and a dress on the third. If you look at style icons, you’ll see that they all have a very consistent style—Audrey Hepburn in her Givenchys; Mrs Kennedy in her sheath dresses or even Madonna in her crucifix and underwear.”

I make a mental note to wear the same style of clothes consistently. But what—sari or sheath dress? That’s the question.

After two days in his company, I go from disdain to dislike to grudging respect to wanting to be liked. I want this man’s respect. Who is your ideal customer, I ask. “The woman who doesn’t need Sabyasachi the brand but understands Sabyasachi the product,” he replies. “Secretly every designer in the world hankers for that kind of customer.”

These days, Shoba Narayan walks up to strangers everywhere and compliments them on their woven saris. Someday she will wear India’s weaves on a regular basis. Write to her at [email protected]

Yup, Aishwarya does like she’s from a Frida Kahlo painting. And I would love to buy the jelelwery she wears as well, the skirts look great too. Even the aprons were exquisite! SLB and Sabya decided the look, I agree, that’s how a movie works. But do you think an actor of Aishwarya’s stature would not have a say in her look? Like when Priyanka Chopra was panned for her look/ clothes/ makeup in Krish, she took full responsibility which means she did have a say BTW, similar to Sabya’s explanation of Aishwarya’s wardrobe, SLB also spoke about it in an interview in yesterday’s Mumbai Mirror, explaining the wardrobe. But I feel a movie should speak for itself. If you need the crew/ cast to give an explanation after the movie’s release, then I’m sorry, the point is lost. Your character’s motivations etc should come through the movie itself, it didn’t come through in this case.Thanks for the link.