Every tourist feels the inherent Bhutanese trait of compassion. It is easy to blend the natural with the supernatural here

Below is a more expansive version of the piece I wrote for Mint Lounge

Does thinking about death five times a day increase your happiness? The Bhutanese seem to think so. Throughout the mountain kingdom, death mixes with life in ways that are subtle, yet beautiful. Consider tsa tsas for instance. Families fashion these tiny stupa-like pyramids using clay mixed with– get this– ashes of dead relatives and leave them as roadside offerings. The ubiquitous prayer flags also memorialize the dead, as do some thangka paintings and chham dances. Funerals are communal affairs– since Buddhists believe in reincarnation, death itself is seen as a new beginning.

This optimistic view is perhaps Bhutan’s draw for grieving folks. A European woman I met at the Amankora Thimphu told me that she had lost her husband during Covid. Visiting Bhutan, for her, was healing, because it gave her “hope” about him being reincarnated and present around her. To seek his spirit, she was on a “quest of happiness” visiting all five Aman properties, she said.

My death-defying experience began on the Druk Air flight from Delhi to Paro. Only 24 pilots in the world can land in Paro, I learned, because it is done manually. As the plane turned sharply in between two mountains, I muttered incoherent prayers, but the landing was smooth.

Bhutan hangs like a necklace on the neck of the Himalayas with India below and China above: a tiny jewel between two large nations. People visit this fabled Land of the Thunder Dragon (Druk Yul in the Dzongkha language) in search of wonder, beauty, enlightenment and yes, happiness, given the country’s measuring tool of Gross Domestic Happiness rather than Gross Domestic Product (GDP). But the Buddhist take on happiness is nuanced, something that I would discover in the coming week, when I visited Paro, Thimphu and Punakha.

A princess was born on the day I arrived. The Dragon King– Druk Gyalpo, Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck, universally revered in the country, and his wife, the Dragon Queen (Druk Gyaltsuen) were parents to a princess after two princes. The whole country was celebrating.

It was the current king’s father who coined the term Gross Domestic Happiness, in a throwaway line during a 1979 press conference, according to the book, “The History of Bhutan” by Karma Phuntsho. Since then, the concept has become a cornerstone of policy and seems to have trickled down to the psyche of the people.

Bhutan ranks high on the World Happiness scale, winning an honourable mention in the latest 2023 report. “When we say happiness in Bhutan, we mean collective happiness, not individual happiness,” said my guide, Namgay Tshering. When asked for examples of measuring happiness, he listed good governance, sustainable development, environmental conservation, and preservation of culture.

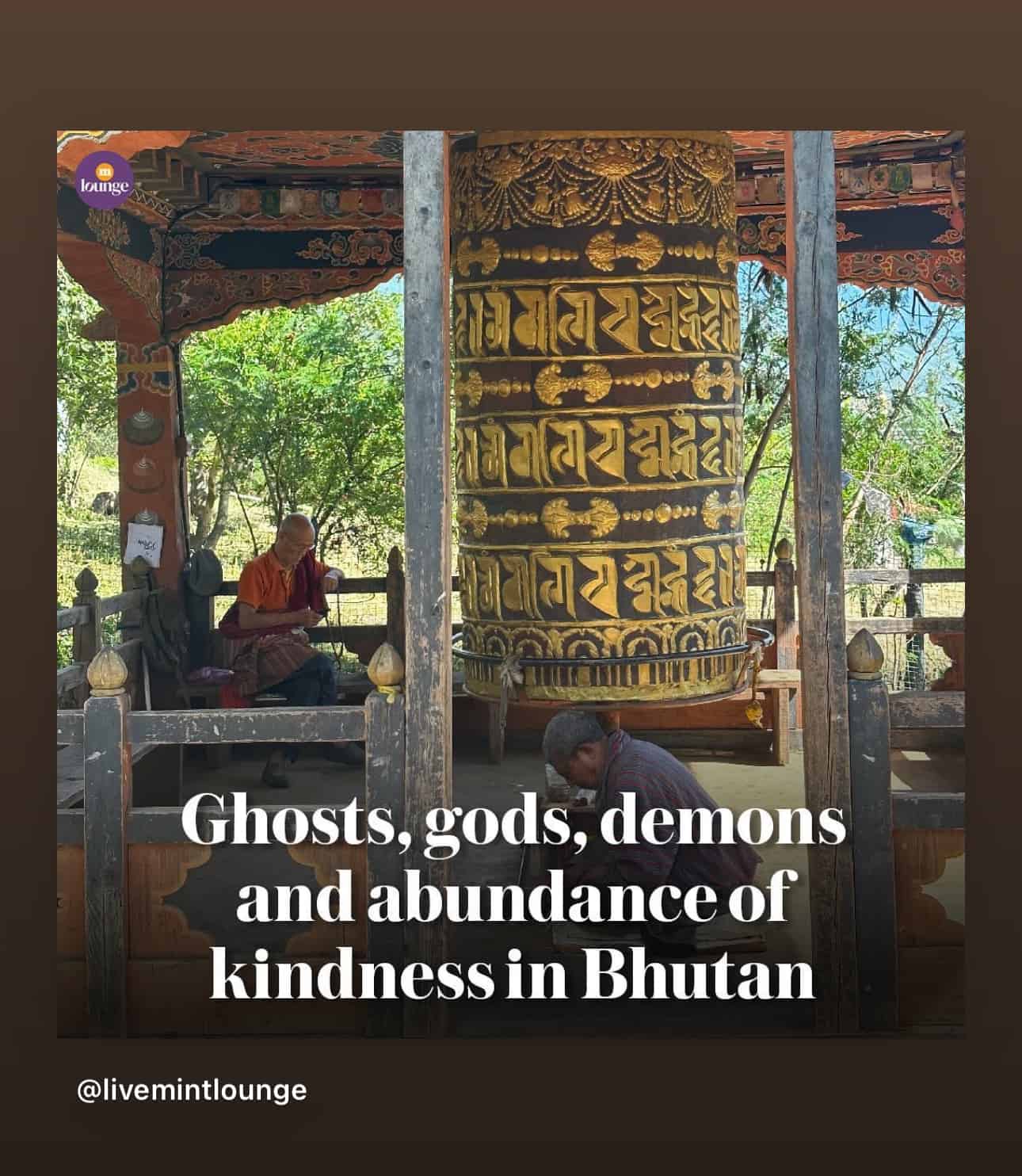

I thought about this as I hiked up to Paro’s Taktsang Monastery or Tiger’s Nest, arguably Bhutan’s most photographed spot. Stunningly picturesque, it clings to a rocky cliff face, 3000 metres above sea level. Legend has it that Guru Padmasambhava (Lotus Born) came here flying on a tiger to subdue a demon and teach Vajrayana Buddhism. Today, the monastery is frequented largely by hardy tourists who make the 5 hour round-trip hike. “My mother has lived in Paro all her life. She has never visited Taktsang,” said our guide.

Cultures, particularly complex ones like Bhutan and India demand more from tourists. James Low, the general manager of the Uma Paro, alluded to this when he talked to me about the two Bhutans– one on the surface level and the other that is ‘felt’ if you have an ‘open heart.’ I understood what he meant because India is the same way. In Buddhism though, an open heart immediately brings to mind the now-popular “loving-kindness” meditation. I saw this in action in every monastery I visited. A common prayer uttered by the monks, and indeed all Bhutanese was a blessing for world peace and happiness. “Tashi Delek,” is a national slogan. Good luck and good health.

The hour-long drive from Paro to Thimphu, the capital, was picturesque. Clouds hung low, veiling homes painted in colours from the land. In Thimphu, my husband and I visited a monk-astrologer at the Pangrizampa College of Astrology. I wanted my horoscope read. Ram wanted no part of it. So I gave him my birth year and got a primer Bhutanese astrology or kyetsi. Everything was about balancing the five elements and 12 zodiac signs. I was born in a horse year, the monk said, and would be well-served by marrying someone from a tiger year, which, as it happened, I did. Our marital ‘elements’ however were not so comforting. I belonged to the fire element and my husband, the water element, which was probably why we have doused and propelled each other throughout our marriage.

Bhutanese believe in divination– much like the Dalai Lama who I once interviewed for this paper. When you live close to the land as they do, when 60 percent of the country is under forest cover, it is easy to blend the natural with the supernatural. Bhutanese take ghosts, gods and demons seriously. At Chimi Lakhang, the fertility temple, people recalled legends about Buddha Drukpa Kunley, the “divine mad monk” who subdued two demonesses by burying them under a stupa, which still stands.

After a day of sightseeing, I walked alone at sunset around the Amankora Thimphu where– I was told– the extended royal family lived. Trees rustled. Streams gurgled. Even I could imagine hungry ghosts and snake gods that required propitiation. In my room, the staff had left protective “chem” rosary beads which I wore before going down for dinner. The Bhutanese thali was terrific with foraged expensive matsutake mushrooms, red rice, fresh greens, and ema datshi, the national dish– soft cheese spiked with fiery chilies.

The Aman gave us (and all departing guests) a Buddhist send-off– a monk blessed our trip. It reminded me of going to prostrate at my grandparents feet before any journey to take their blessings. This belief in a higher power binds Hinduism and Buddhism.

The drive from Thimphu to Punakha– the current ‘it’ spot in Bhutan took four hours. As a birdwatcher, I was in heaven, quite literally. We traversed Dochula pass (3100 metres elevation) with a great view of the Eastern Himalayas. We descended to Lamperi gardens where minlas, barbets, laughing thrushes, niltavas and warblers thronged the bushes. I didn’t know where to look. With 775 bird species, and a staggering number of flora and fauna, Bhutan is among the most biodiverse countries in the world, especially given its tiny size.

In Punakha, we spent two days at the newly opened Punakha River Lodge, operated by andBeyond, the South Africa luxury lodge brand. Set amidst paddy rivers and surrounded by the Mo Chu river and mountains, the lodge felt like being in the heart of Bhutan. We visited the famous Punakha dzong, where coronations take place, rafted the river, hiked up to see spectacular monasteries with colourful wall murals, and enjoyed a surprise breakfast put forth by the hotel right beside the temple. Climbing up and down the mountains was hard but our minds were light, perhaps because we were engaged in what the Japanese call “Shinrin roku” or forest-bathing.

All too soon, it was time to drive back to Paro airport. On the drive back, I called former model and actor Kelly Dorjee, who now ran a high-end travel company to ask him what was distinctive about his country. “Bhutan has chosen the path less travelled—to protect its forests, its culture, and cultivate a kinder and more mindful society,” he said.

Kindness was abundantly on offer. I saw it on my last lunch at Your Cafe– run mostly by women, and popularized by Deepika Padukone’s visit, posted on Instagram. When I went to use the restroom, I saw about 20 young performers, dressed in chham masks and costumes. They were going to perform for a large group of tourists. We got talking. They were in college and worked part-time as performers to make extra money. I asked them about the themes that the dances portrayed and what they considered important in their culture. To a person, they said, “kindness.” They used different words, of course. Some said loving-kindness; some said compassion; tolerance; generosity. But the gist was clear and it was all about giving.

This inherent Bhutanese trait– called karuna in Sanskrit and nyinjay in Dzongkha, is felt by every tourist visiting Bhutan. It is perhaps why so many return. Having a concentration of Aman lodges doesn’t hurt either.

Leave A Comment