From hippie to hipster paradise: for Condenast Traveler US edition

by Shoba Narayan

September 9, 2008

COVER STORY

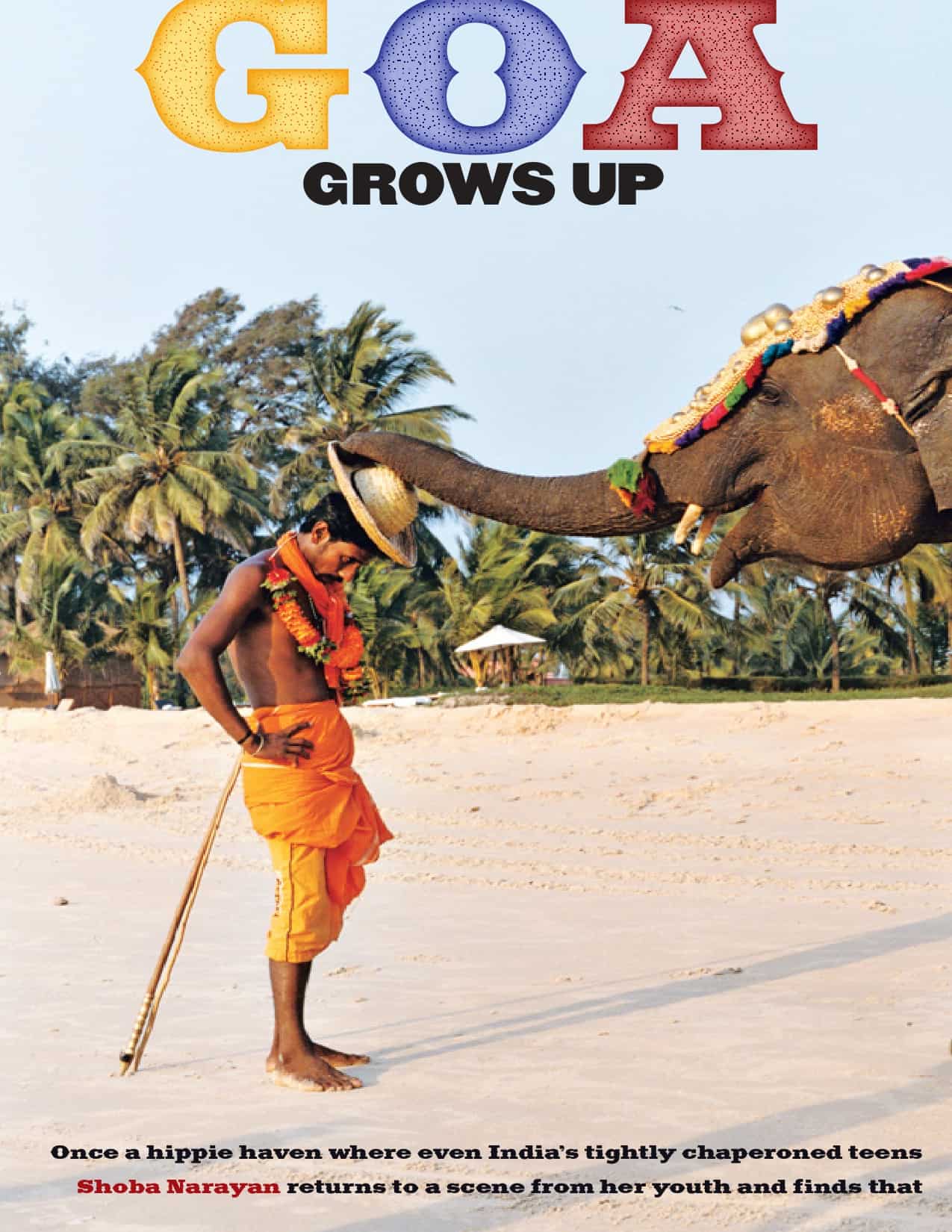

Once a hippie haven where even India’s tightly chaperoned teens could turn on, tune in, and drop out, Goa has lately gone upscale. Shoba Narayan returns to a scene from her youth and finds that Goa (like the author herself) has only gotten better with age

Goa Places and People PDF here

It is Christmas in Goa. The sun-dappled veranda of Alban and Maria Couto’s sprawling ancestral hacienda is as good a place as any to discuss the future of India’s smallest state. Old family friends, they are in their sixties, maybe seventies—I dare not ask. Even though I’ve met them only twice, I call them Auntie and Uncle, Indian style. Alban, dapper in suspenders and tie, served in the Indian Civil Service with my in-laws; Maria, regally composed, is an acclaimed author. I have brought along her book Goa: A Daughter’s Story, for an autograph.

After hellos and small talk about Aldona, the tiny enclave in which they live, we settle down. What, they ask, will I have to drink?

“Orange juice?” I reply doubtfully. (It is before noon.) Alban looks at me with pity. We will have feni,he announces. I should have known. Goans drink feni (thirty-five percent alcohol) at weddings and wakes, baptisms and birthdays, after butchering a pig and before lunch. A Goan home, the saying goes, will lack anything but liquor. Maria opts for white wine. Their man Friday brings me a shot glass and some salted cashews.

The feni is velvety smooth and fiery. I shake my head at its potency. Seeing what he takes to be my appreciation, Alban summons his Jeeves again. “Take an empty Sprite bottle and fill it with feni for madam,” he says, chuckling at the duplicity of the act. My head buzzes.

“Goa has changed, hasn’t it?” I begin, with a wide, somewhat silly smile. A who’s who seems to be moving in: Bombay socialites, photographer Dayanita Singh; why, I heard that author Amitav Ghosh has bought here, too. Turns out that Ghosh is their neighbor. Later, during a tour of the house, I spot his books in Alban’s library, each lovingly inscribed.

The Coutos are both descended from Brahmin families who were converted to Christianity by the Portuguese in the sixteenth century, something that Maria recounts in her book. Worldly and well traveled, with a son in the United States and a British daughter-in-law, they could live anywhere, yet they chose Goa.

“It is a place where you can shed your inhibitions,” says Alban. “Revel in simple pleasures. Goa is about . . . the good life.” A life they fear is fast disappearing. “Goa has a wistful, elegiac quality to it,” says Maria, sounding wistful herself. “And this quality is contained in Goan music: both joyful and sad.”

They tell me about their neighbor, a poor farmer who came to them with a sob story about needing money. Generations of his people had toiled on their land and he was heavily in debt, so the Coutos transferred title of a plot to the man—only to discover that he turned around and sold it for a small fortune. “What he doesn’t realize, the poor fool, is that he now has no place in Goa to live,” says Maria. “All these outsiders come in and tempt the locals with wads of cash.”

At the Coutoses’ recommendation, I call political cartoonist Mario Miranda, a living legend in Goa. I introduce myself as a journalist, and apologize for intruding on his Christmas holiday.

“Hate Christmas,” Miranda cuts me off. “Hate being forced to be happy.”

When I ask to see him, he demurs. Five minutes, I beg. I am a friend of the Coutoses.

Later that afternoon, Mario Joao Carlos do Rosario de Britto Miranda—gray-haired and with keen eyes—receives me in his study. “Call me Mario,” he says. The high ceilings, orange walls, black-and-white drawings, ancient typewriter, and gramophone all make it feel like a European salon or a well-preserved Park Avenue penthouse. I am tongue-tied. I congratulate him on his numerous awards, on the lifetime-achievement honor he received from Louis Vuitton a couple of years ago. I was at the post-award party, but Miranda never showed. “Hate parties,” he says, waving off my praise. He asks about my life in Bangalore and, before that, New York, where his elder son is a coiffeur. I ask about Goa’s future.

“Goa is finished, as far as I am concerned,” he replies. He tells me about his neighbors, a Brit and a Kiwi. Lovely people, he says, leading the good life with Vespas and an in-ground swimming pool. However, Goans are now a minority in Goa, he claims.

Like the Coutoses, Miranda honors his Hindu roots. His ancestors promised to deliver a sack of rice and a hundred coconuts to the local temple of the goddess Durga at the start of each harvest, he tells me—a commitment they’ve kept to this day, even though their lands have been disposed of and “Portuguese is my mother tongue.”

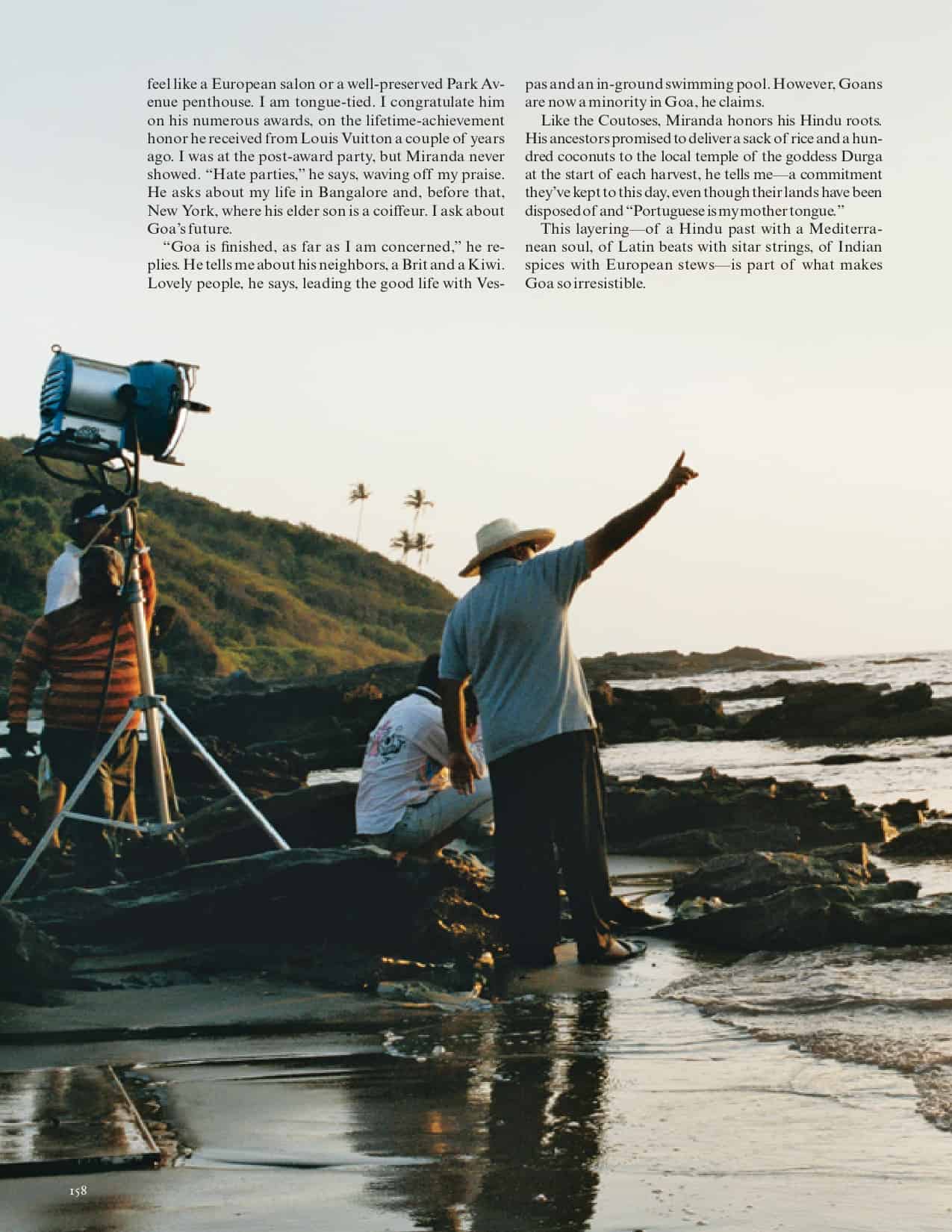

This layering—of a Hindu past with a Mediterranean soul, of Latin beats with sitar strings, of Indian spices with European stews—is part of what makes Goa so irresistible.

That evening, I stroll down Arossim Beach from my hotel in South Goa to a makeshift shack and order a beer. All around me are singles and couples—a rainbow of colors and predilections—reading books, nibbling on shrimp, listening to local musician Remo Fernandes’s hit “Muchacha Latina” on boom boxes. Anywhere else in India, I—an unaccompanied woman—would be the object of curiosity and questions. Here, nobody looks at me twice. Solitude, a multi-hued sunset, a salty breeze loosening tendrils of my upswept hair, all topped with a brawny beer—to be sure, this is the good life. No wonder the foreigners came.

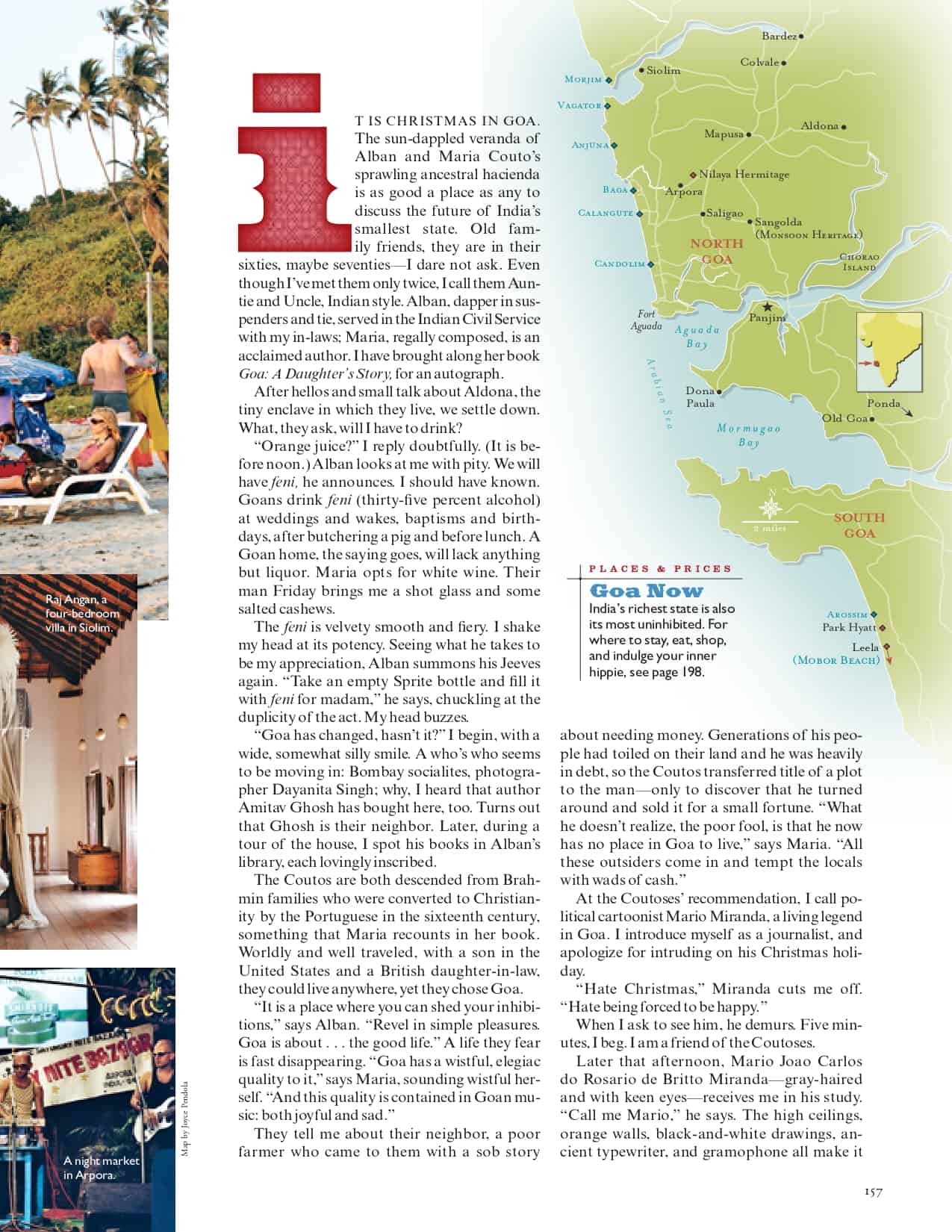

The Portuguese were the first to occupy India and the last to leave, arriving with Vasco da Gama in 1498 and departing a mere forty-five years ago at the behest of the Indian army. Since its “liberation,” Goa has accumulated many plaudits. India’s smallest state is also its richest, with a high rate of literacy and few beggars. Barely industrialized, it is less a cohesive entity than it is a collection of villages, or communidads, with musical names like Calangute and Candolim, Mapusa and Morjim, all delivered in lilting Konkani.

I decide to start in South Goa and work my way up the coast. Goa has resorts and homestays to suit every budget, but most are booked a year in advance. The more popular ones sometimes require a minimum stay of a week during high season, which begins in October and ends in March. In my view, the best time to visit is late December and early January. Just as Kerala is decked out for the Onam festival in September and Delhi is best seen during Diwali (India’s biggest Hindu holiday) in October, Goa is at its most magical during Christmas and New Year. Christians comprise only thirty percent of the population, but they are an expressive and highly influential presence.

On Christmas night, I accompany Andrew Pegado to a village dance. Pegado is a photographer who covers parties for the local papers. Tonight he is off duty, but he nevertheless carries his camera because, he says, you never know when a celebrity will show up.

Silver Bells, the outdoor dance hall in Sangolda, is prettily lit. Pegado greets friends—a kiss on each cheek for the women, a handshake or hug for the men, depending on the level of friendship. He hands me a gin and tonic from the cash bar and goes to mingle. The hall is full of couples and families. The women are decked out in long dresses, and the men in either suits or black tie. A band named Alcatraz comes onstage and begins to play—the fox-trot, the rumba, the samba, the swing. To my surprise, the floor fills up with couples, the men as graceful as the women. One twosome cradle a baby as they waltz. Little girls in flouncy dresses and boys in jackets and trousers freestyle in between the adults. It is like being at a family camp in the Poconos—cheesy but oddly charming.

I observe an Indian couple dancing cheek to cheek. They are plump and not particularly attractive but move with impeccable rhythm and grace. This is new to me—Indian men are not known for their dancing. I make bold: I tap the lady on the shoulder and steal off with her partner. Turns out he is a real-estate agent and knows of a beachfront property. It’s technically too close to the water to build on, he says, which is why it’s so cheap. But he assures me that a big hotel chain (he won’t say which) is building even closer to the shoreline and so I should be fine. Louis Armstrong’s timbral voice wafts in from somewhere: “What a wonderful world,” he croons. I take it as a sign.

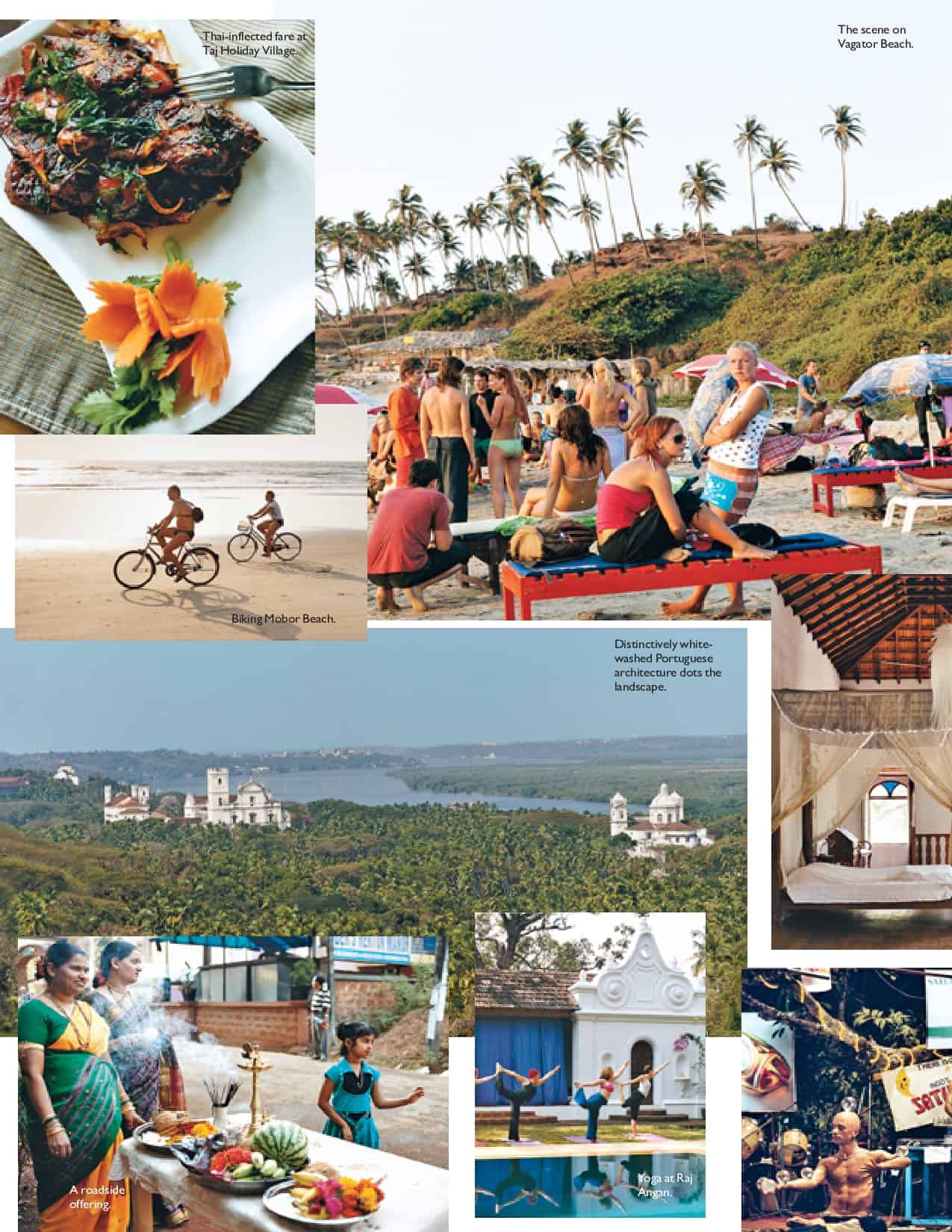

South Goa may be quiet—and justly renowned for its beaches—but North Goa is where the action is. The seashore at Baga, Calangute, and Candolim is full of sunbathing bodies, sometimes nude. Masseurs and reflexologists ply the sand. And as the sun sets, nightclubs like Britto’s and Tito’s pump out music.

As I sunbathe on Baga Beach, getting a back massage with clove oil, my real-estate agent/dance partner calls back with figures. All they want is $1 million, he says. I jump up, scalded not by the sun but by the soaring prices. It feels like New York all over again. I decide I’m not that fond of beaches after all.

Leaving Baga, I encounter rice paddies and palm groves. White egrets take flight from lotus ponds. Crocodiles swim among the mangroves. Europeans on scooters speed down the narrow rural roads, dodging chickens, cows, dogs, and pigs. I chase them on my rented Vespa, determined to find their secret hideouts. Which is how I end up at the end of a long dirt road, saying hello to Yahel Chirinian and Doris Zacheres.

Foreigners feel at home here. They come on holiday and end up staying for years. Chirinian and Zacheres, for instance, met in Paris and moved to Goa eight years ago. Together, they own Monsoon Heritage, designing and building startlingly whimsical sculptural pieces for collectors here and abroad. They love India, Chirinian says, because the “weather is brutal, the snakes poisonous, and the friendships profound.”

German Claudia Derain and her Indian husband, Hari Ajwani, are another such couple, having opened the magical Nilaya Hermitage, an eleven-room hotel with a cult following, fourteen years ago. Englishman James Foster, another expat, manages Casa Boutique Hotels, a chain whose accommodations have the feel of bungalows. In fact, the only foreigners who don’t seem plentiful these days are the Portuguese.

“Goa has a special vibration, a Latin feel,” says fashion designer Wendell Rodricks, one of the few openly gay Indians. Rodricks lives with his French partner, Jerome Marrel, in a beautifully restored Portuguese mansion in Colvale.

I visit Rodricks on the eve of his spring fashion show. It is midmorning. He sits outside under a banyan tree, sketching and describing the model lineup to an assistant. A manservant brings breakfast: fresh fruit juice, green tea, and oatmeal on a stylish wooden tray. Five dogs lounge around Rodricks’s feet, occasionally nuzzling his Prada sandals; Marrel sits on a balcony above us, reading. It is a cozy domestic scene, and I want it all—the restored Portuguese mansion, the manservant, the dogs, and, if possible, the Prada sandals.

Although his flowing monochromatic designs have long been scooped up by India’s most stylish women, Rodricks feels that he “bloomed” as a designer only after moving to Goa in 1993. Today, he lives an idyllic life: walking the village and sketching in the morning, spending the bulk of his day at his shop in Panjim, going out on his boat at sunset, and attending a different soirée almost every night. “I was at a party last night where I was the only Goan,” he says. “Lots of international citizens live here, a life that is part lotus-eater, part evolved globe-trotter.”

Living in a trading port for the Greeks, Romans, Arabs, and Europeans meant that Goans were forced to interact with the outside world far earlier than the average Indian. This has made them friendly but not overly curious about foreigners. Unlike in the rest of India, white people don’t get stared at here, even in the most rural settings. Trance music and tranquil beaches nudge type A personalities into subdued sublimity. The heat and, yes, the hashish encourage a languid pace of life and a state of mind that Goans call sussegado, political cartoonist Miranda told me. “It means a life of leisure—and it is vanishing.”

A couple of years ago, a group of concerned citizens began a Save Goa campaign to prevent the government from converting off-limits agricultural land into Special Economic Zones (SEZs) subject to development. Everyone I meet is up in arms—against the “Russian mafia,” who are buying large tracts near Morjim Beach, where the olive ridley sea turtles come to nest, and against nouveau riche North Indians who are buying up Goa without respecting its values.

Upendra Gaunekars and his wife, Sangeeta—an old, aristocratic Hindu family in hilly Ponda—say the solution lies in green businesses that suit Goa’s psyche. They talk with pride of the “Nylon 66” agitation that forced the DuPont chemical company to withdraw from Goa. It reminds me of a Southern gentleman I once met in Memphis who told me that the difference between a Yankee and a damn Yankee is that Yankees go back home.

“Goans don’t want development. We want our heritage to continue,” says Sadiq Sheikh, a fourth-generation Goan. Sheikh lives high on a hill in tony Dona Paula, with stunning, sweeping views of the Mandovi River. “I own everything you see,” he says matter-of-factly. Behind us is a development of bland two-bedroom apartments, built by a businessman to whom Sheikh sold the land. If I didn’t know better, I’d think I was in New Jersey.

Sheikh rues the pace of construction but is not sure how to stop it. “We don’t want spoiled brats from other states to come in and polarize Goa,” he says. “But how can I censor whom I sell my land to? How can I control what they do with it once they buy it?”

The Save Goa folks would argue that Sheikh shouldn’t sell his land at all. Armando Gonsalves is a jazz musician and real-estate agent who owns several waterfront acres right beside Sheikh’s. Gonsalves has dreams of converting it into an eco-village or a jazz community—he’s not sure which. He knows it doesn’t make business sense, but he believes that green development is the only thing that will preserve his Goa. “For me, Goa is life itself,” he says without a trace of theatrical exaggeration.

Gonsalves runs a nonprofit called Heritage Jazz that holds concerts in historic buildings, including his own home, which occupies an entire city block in Central Panjim. Walking into the Gonsalves mansion is like visiting Portugal circa 1940: a faintly sepulchral silence pervades the cool, dimly lit rooms furnished with ornately carved antiques.

We sip tea from delicate pink china and nibble on bibinca, a coconut layer cake that is a Goan specialty. Gonsalves introduces me to Reboni Saha, an attractive architect who is also a Save Goa activist. Saha, whose mother is German, bounced around Europe for years before settling in Goa. “In Goa, there is no prejudice,” she says. “As a single woman, I felt safe. I wasn’t pigeonholed. Maybe it’s because of the hippies.”

Of course, it was the hippies from America and England who helped put Goa on the map in the 1960s, drawn by the pristine beaches and laid-back lifestyle. A decade later, Goa was still the only place in India where otherwise carefully chaperoned Indian kids like me could escape for a weekend of sex, drugs, and rock and roll. Accessible from any major metropolis by bus, train, or air, it was party central. Beach shacks could be rented for a hundred rupees (about three dollars) a night for days or months at a time.

Like the rest of us, Goa has grown up in the intervening years. Some of the best things remain: Women can still sunbathe topless on Candolim Beach (or watch others do it). The beach shacks still serve up some of the country’s freshest seafood (and coldest beer). And the Goanese spirit—equal parts Portuguese joie de vivre and cloistered Catholicism—has given rise to some of the most interesting artists and designers in India.

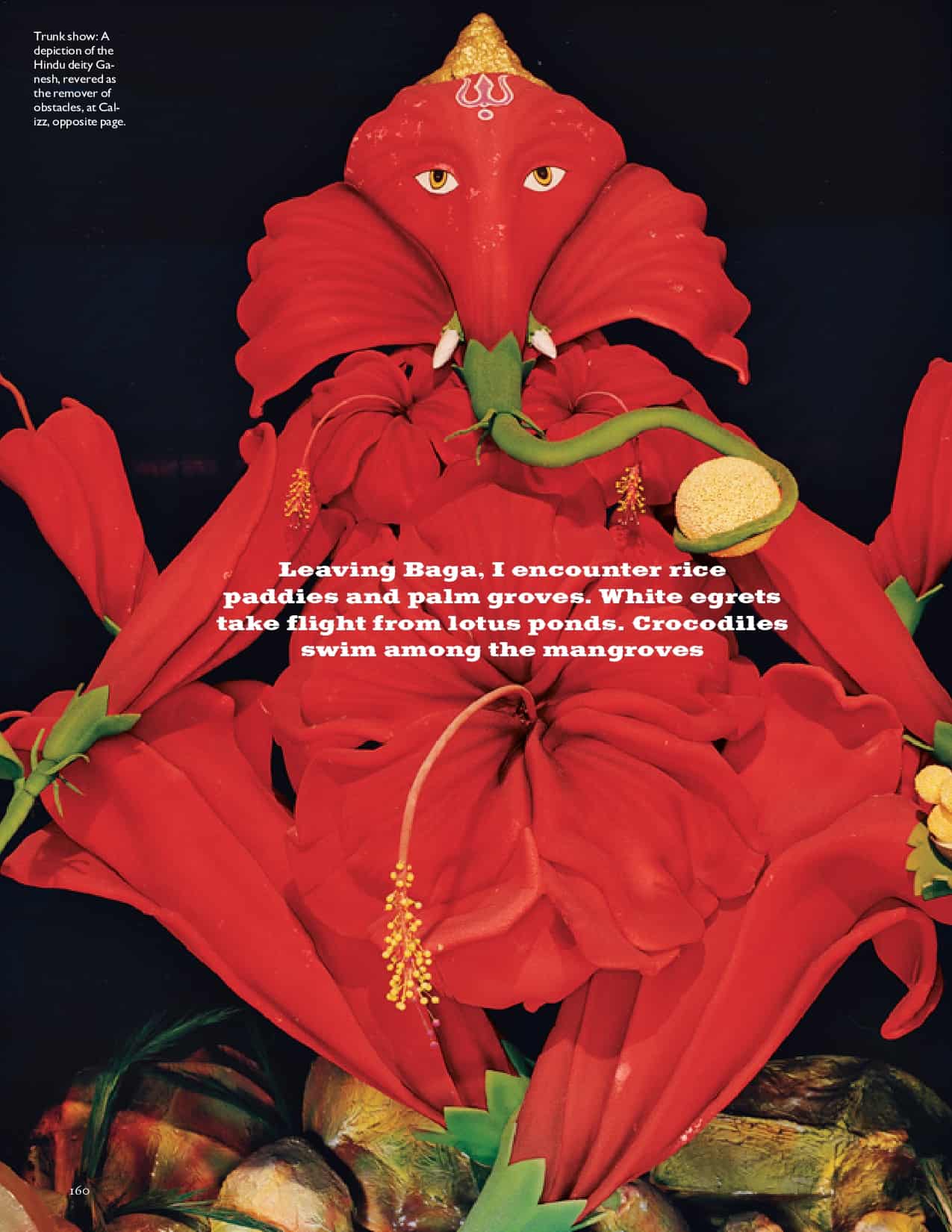

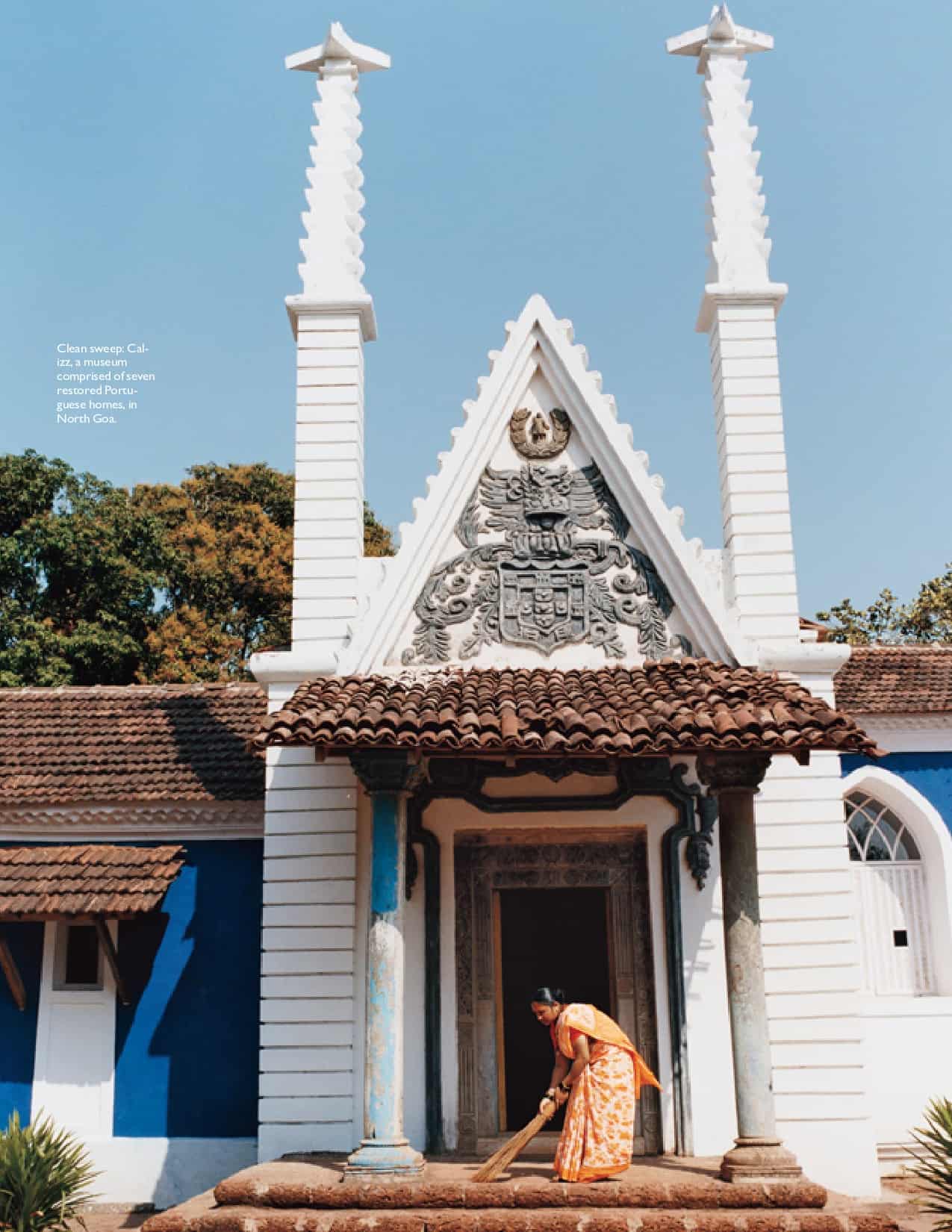

“Portugal did Goa a great favor,” says architect Gerard da Cunha. “We were cut off from the shackles of Indian tradition. We were forced to look outside.” Da Cunha is my last stop. He tells me about Goan music and the state’s distinctive mix of spices, and he takes me on a tour of Calizz, the museum he has fashioned from seven traditional Goan homes, which juxtapose Indian-style courtyards and verandas with the Portuguese penchant for high-ceilinged rooms and terra-cotta roofs. “Architecturally, it may be one of the richest hybrids there is,” he says.

Naturally, what follows is a lament over how quickly it is all changing. “There is a temper to this place that is getting eroded; it upsets me greatly.”

Nostalgia aside, what now for Goa? Personally, I don’t see much to worry about. The day before I leave, newspapers carry a warning from the Save Goa activists demanding that tourists leave Goa. It is no longer safe, scream the headlines.

We have to say these things, counter the agitators with a nudge and a wink—only then will the government take us seriously; after all, tourism is Goa’s lifeblood. Sure enough, the government bows to public pressure: The next day it announces an end to all SEZ development. Such is the power of Goa’s red earth. It reminds me of something Wendell Rodricks told me. “The way I love Goa,” he said, “if someone told me to eat the soil, I would.”

As for my own urge to buy in, I decide to do Goa a favor: I walk away. My motives aren’t entirely altruistic, though. They spring from something architect Gerard da Cunha said. “You know, it is always the marginals who discover paradise,” he told me when we bid good-bye. “Guess where the hippies are these days? In Gokarna.”

So I rent a car and drive 150 miles south to the tiny village of Gokarna. Sure enough, I find my hippies. And, who knows, maybe even my own piece of paradise—for a quarter of the cost.

END MAIN STORY

Goa: Places+Prices

Going from North Goa to South Goa takes nearly two hours, so shuttling between the two is not as easy as one might think for such a relatively tiny state. Stay in North Goa if you like buzz and beaches, South Goa if you prefer peace and quiet.

In North Goa, Calizz is a collection of restored Portuguese homes that offers a wonderful tour of Goa through the ages (832-325-0000). Visit the Salim Ali Bird Sanctuary by boat with guide Uday Mandrekar to spot Goa’s many winged visitors (982-258-3127). A number of the luxury hotels have casinos, but for a completely different experience, visit the one aboard the MV Caravela, off Panjim Harbor (832-669-5000). Sample the music scene at Butter, a newish nightclub in the heart of Candolim (Candolim-Sinquerim Rd., near Acron Arcade)—or Sweet Chilli, where local bands play live music most nights (near Fort Aguada). Nine Bar has funky DJs and is an ideal place to watch the sun set (off Vagator Beach).

The country code for India is 91. Rates quoted are for October 2008.

Lodging

In North Goa, the 140-room Taj Holiday Village, which draws Bollywood film stars and Bombay socialites, provides easy access to popular beaches and nightclubs (832-664-5858; doubles, $175–$600). The 180-year-old, family-owned, 24-room Panjim Inn’s greatest asset is its location: bang in the heart of the Latin district, Fontainhas. All around are purple-colored homes, boys playing cricket, and fruit vendors selling plump “loose-jacket” oranges (832-222-6523; doubles, $40–$85). Perched atop a hill, the Nilaya Hermitage has 11 stylish rooms overlooking the treetops and the twinkling sea. The all-inclusive rate is high but doesn’t deter the many repeat guests (832-227-6793; doubles, $525). In a lovingly restored 300-year-old Portuguese mansion, the seven-room Siolim House has its own eight-cabin sailboat, Jabuticaba (832-227-2138; doubles, $85–$105). Fashion photographer Denzil Sequeira is the fourth-generation owner of the secluded ten-room Elsewhere, where Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt are said to have stayed during a recent holiday (932-602-0701; doubles, $1,970 per week, with a seven-night minimum in high season). Perched high in the Western Ghats, a couple of hours inland, Wildernest Goa’s 16 eco-cottages are a haven for birdwatchers and nature lovers (988-140-2665; doubles, $150–$250).

In South Goa, the 250-room Park Hyatt—with hacienda-style villas, five restaurants, an award-winning spa, and a huge free-form pool—is hard to beat (832-272-1234; doubles, $175–$245). The 75-acre Leela sits along one of Goa’s prettiest beaches. The 185 minimalist rooms were recently refurbished, but the service was spotty during my visit (832-287-1234; doubles, $135–$705). The charming Vivenda dos Palhaços, in the middle of a Goan village, gives a glimpse of rural life—complete with crowing cocks, grunting pigs, and church song. The hosts are friendly, and the seven rooms, while modest, are furnished with flair (832-322-1119; doubles, $110–$200).

Dining

In North Goa, Fiesta serves Continental food on bustling Baga Beach (7/35 Sauntavado; 832-227-9894; entrées, $11–$20). Souza Lobo has been offering decent Goan food for some 70 years from a prime spot on Calangute Beach (832-228-1234; entrées, $7–$12). Plaintain Leaf (Calangute Beach Rd.; 832-227-6861; entrées, $7–$10) and Little Italy (136/1 Gauravaddo, Calangute; 932-601-3324; entrées, $8–$15) are nirvana for vegetarians, serving tasty Indian and Italian, respectively. Lila Café is known for its all-day breakfast, outdoor seating, and friendly if unhurried service (Arpora-Baga; 832-227-9843; entrées, $5–$12). For seafood, hit beach shacks like Bobby’s, near the taxi stand on Candolim Beach (no phone; entrées, $1–$3), and Curlies on Little Anjuna Beach (no phone; entrées, $1–$3), which serve fish-and-chips along with the catch of the day. Most of the luxury hotels have noteworthy restaurants. Particularly good are the Thai-themed Banyan Tree at Taj Holiday Village (entrées, $8–$15), Goan fare at the Park Hyatt’s Casa Sarita (entrées, $10–$18), and the Leela’s Jamavar, for its opulent Indian (entrées, $12–$18).

While South Goa has a lot of homey eateries, it lacks the buzzy restaurants of North Goa. One exception is the family-run Martins Corner, renowned for its fish and pork dishes (Binwaddo, Betalbatim, Salcette; 832-288-0413; entrées, $4–$10).

Reading

Candolim’s Oxford Bookstore has a wide variety of books on Goa (Acron Arcade, Fort Aguada Rd.; 832-287-1391)—including Maria Couto’s Goa: A Daughter’s Story, a well-researched memoir soaked in the state’s turbulent past (Penguin, $17). Dominic’s Goa, by Dominic Fernandes, is a collection of essays that touches upon pretty much every aspect of daily life (Abbe Faria Productions, $8). How to Be an Instant Goan, by Valentino Fernandes, is easy reading and occasionally hilarious (Diamond Publications, $4). Houses of Goa, a richly photographed coffee table book by Annabel Mascarenhas and Heta Pandit, offers an inside view of Goan life (M&M Publications, $45).

–Shoba Narayan

Markedly well written piece

I couldnt think you are more right..

This post could not be more on the level…

Thats an all round amazing blog..

Hiya. I noticed your blog title, “Goa Grows Up: Condenast Travel October 2008 issue ”

doesn’t really reflect the content of your website.

When writing your site title, do you think it’s

most beneficial to write it for Search engine optimization or for your viewers?

This is one thing I’ve been battling with simply because I want good search rankings but at the same time I

want the best quality for my site visitors. – ABC102D.