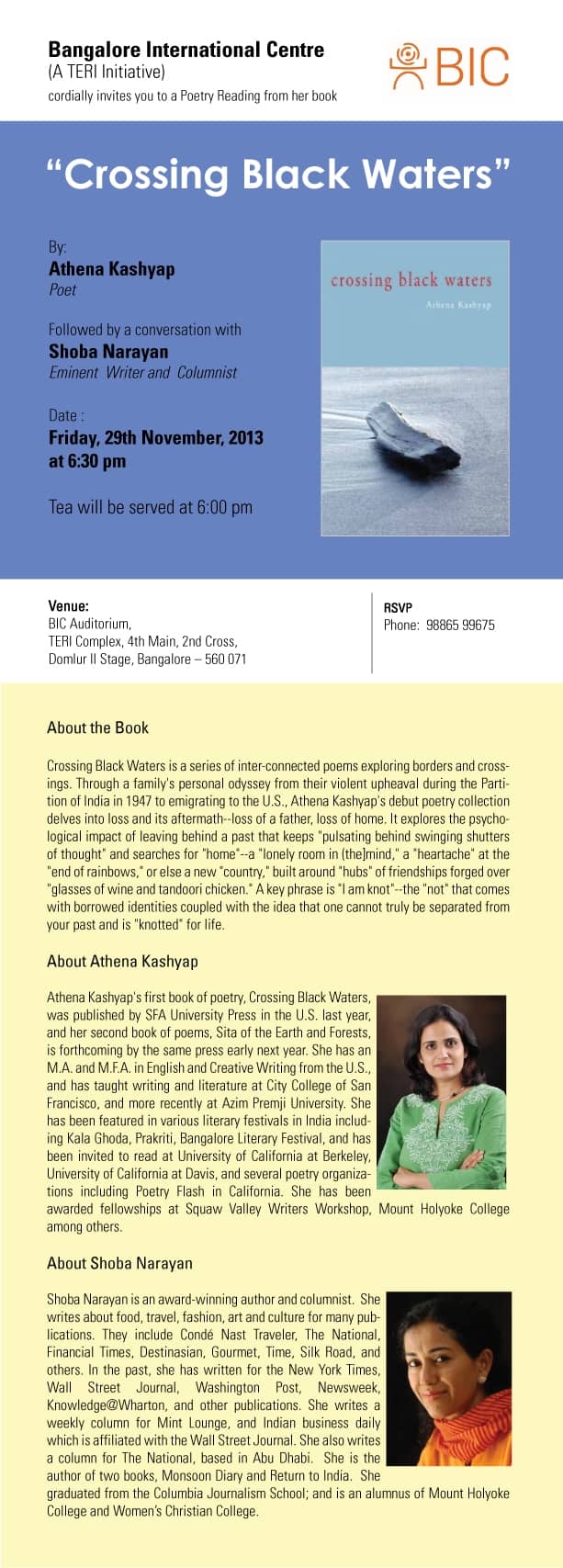

If any of you are in Bangalore tomorrow, I am moderating a poetry reading by Athena Kashyap. Please come.

I am fascinated by poetry: the musicality of it; how to make words sing; how to condense thought. So I thought I would engage Athena in a discussion about the whys and how of poetry writing. I will begin by having Athena talk about her book and read a short excerpt. And then, I will widen the scope to poetry in general.

In preparation, I went to the site that I always turn to: The Paris Review Interviews. This time with poets.

Over the course of two delicious hours of readings, I chose a few poets who spoke to me and noted down their questions.

Art of Poetry interviews here.

Based on reading these, I thought I would ask Athena these questions.

1. Why poetry? Why is poetry important to society? My favorite reason is what Paz said below, but I’d like to see what she says.

Octavio Paz

1991

“If a society without social justice is not a good society, a society without poetry is a society without dreams, without words . . . and without that bridge between one person and another that poetry is. If society abolishes poetry it commits spiritual suicide.”

2. Why did you choose poetry? As opposed to novels or non fiction?

3. Does it come easy to you? What is the process by which you write poetry?

Yves Bonnefoy, an amazing French poet answered it thus here. Beautiful, non?

So I jot down these sentences. I listen to them. I see them making signs to each other, and thanks to them I begin to understand needs, memories, fantasies which are within me. This is the beginning of the poem, which will eventually become a whole book, since it will concern all that I am. I have always started in this way, in the middle of the unknown, only to discover later that I was speaking from the point that would have been the simple observation of my daily actions and thoughts. This is a labor that requires a great deal of time, years perhaps. Often the title comes at the end, like a retroactive statement.

4. What times of day do you write? By longhand or computer? Where do you sit? What is your muse? Process please?

Maya Angelou described it here. I’d like to hear Athena’s process.

INTERVIEWER

You once told me that you write lying on a made-up bed with a bottle of sherry, a dictionary, Roget’s Thesaurus, yellow pads, an ashtray, and a Bible. What’s the function of the Bible?

MAYA ANGELOU

The language of all the interpretations, the translations, of the Judaic Bible and the Christian Bible, is musical, just wonderful. I read the Bible to myself; I’ll take any translation, any edition, and read it aloud, just to hear the language, hear the rhythm, and remind myself how beautiful English is. Though I do manage to mumble around in about seven or eight languages, English remains the most beautiful of languages. It will do anything.

INTERVIEWER

Do you read it to get inspired to pick up your own pen?

ANGELOU

For melody. For content also. I’m working at trying to be a Christian and that’s serious business. It’s like trying to be a good Jew, a good Muslim, a good Buddhist, a good Shintoist, a good Zoroastrian, a good friend, a good lover, a good mother, a good buddy—it’s serious business. It’s not something where you think, Oh, I’ve got it done. I did it all day, hotdiggety. The truth is, all day long you try to do it, try to be it, and then in the evening if you’re honest and have a little courage you look at yourself and say, Hmm. I only blew it eighty-six times. Not bad. I’m trying to be a Christian and the Bible helps me to remind myself what I’m about.

INTERVIEWER

Do you transfer that melody to your own prose? Do you think your prose has that particular ring that one associates with the King James version?

ANGELOU

I want to hear how English sounds; how Edna St. Vincent Millay heard English. I want to hear it, so I read it aloud. It is not so that I can then imitate it. It is to remind me what a glorious language it is. Then, I try to be particular and even original. It’s a little like reading Gerard Manley Hopkins or Paul Laurence Dunbar or James Weldon Johnson.

INTERVIEWER

And is the bottle of sherry for the end of the day or to fuel the imagination?

ANGELOU

I might have it at six-fifteen a.m. just as soon as I get in, but usually it’s about eleven o’clock when I’ll have a glass of sherry.

INTERVIEWER

When you are refreshed by the Bible and the sherry, how do you start a day’s work?

ANGELOU

I have kept a hotel room in every town I’ve ever lived in. I rent a hotel room for a few months, leave my home at six, and try to be at work by six-thirty. To write, I lie across the bed, so that this elbow is absolutely encrusted at the end, just so rough with callouses. I never allow the hotel people to change the bed, because I never sleep there. I stay until twelve-thirty or one-thirty in the afternoon, and then I go home and try to breathe; I look at the work around five; I have an orderly dinner—proper, quiet, lovely dinner; and then I go back to work the next morning. Sometimes in hotels I’ll go into the room and there’ll be a note on the floor which says, Dear Miss Angelou, let us change the sheets. We think they are moldy. But I only allow them to come in and empty wastebaskets. I insist that all things are taken off the walls. I don’t want anything in there. I go into the room and I feel as if all my beliefs are suspended. Nothing holds me to anything. No milkmaids, no flowers, nothing. I just want to feel and then when I start to work I’ll remember. I’ll read something, maybe the Psalms, maybe, again, something from Mr. Dunbar, James Weldon Johnson. And I’ll remember how beautiful, how pliable the language is, how it will lend itself. If you pull it, it says, OK.” I remember that and I start to write. Nathaniel Hawthorne says, “Easy reading is damn hard writing.” I try to pull the language in to such a sharpness that it jumps off the page. It must look easy, but it takes me forever to get it to look so easy. Of course, there are those critics—New York critics as a rule—who say, Well, Maya Angelou has a new book out and of course it’s good but then she’s a natural writer. Those are the ones I want to grab by the throat and wrestle to the floor because it takes me forever to get it to sing. I work at the language. On an evening like this, looking out at the auditorium, if I had to write this evening from my point of view, I’d see the rust-red used worn velvet seats and the lightness where people’s backs have rubbed against the back of the seat so that it’s a light orange, then the beautiful colors of the people’s faces, the white, pink-white, beige-white, light beige and brown and tan—I would have to look at all that, at all those faces and the way they sit on top of their necks. When I would end up writing after four hours or five hours in my room, it might sound like, It was a rat that sat on a mat. That’s that. Not a cat. But I would continue to play with it and pull at it and say, I love you. Come to me. I love you. It might take me two or three weeks just to describe what I’m seeing now.

Athena: what poets do you like? What are your influences.

Seamus Heaney said it thus and you can see how familiar he is with these poets. Wish I could have such knowledgeable reactions about poets but I don’t. I am looking forward to what Athena says.

INTERVIEWER

Is Yeats a political poet?

HEANEY

Yeats is a public poet. Or a political poet in the way that Sophocles is a political dramatist. Both of them are interested in the polis. Yeats isn’t a factional political poet, even if he does represent a definite sector of Irish society and culture and has been castigated by Marxists for having that reactionary, aristocratic prejudice to his imagining. But the whole effort of the imagining is towards inclusiveness. Prefiguring a future. So yes, of course, he is a poet of immense political significance, but I think of him as visionary rather than political. I would say Pablo Neruda is political.

INTERVIEWER

What about W.H. Auden?

HEANEY

Is it too sophisticated to say Auden is a civic poet rather than a political poet?

INTERVIEWER

I remember your saying in an essay that Auden introduced to English writing of his era a regard of contemporary events, which had been neglected.

HEANEY

There are poets who jolt the thing alive by seeming to lift the reader’s hand and put it on the bare wire of the present. It’s a matter of cadence and diction quite often. But Auden did set himself up for a while very deliberately as a political poet. Certainly up until the early 1940s. And then he becomes, if you like, a meditative poet. A bit like Wordsworth. At first a political poet with a disposition that is revolutionary. And then come the second thoughts. But as Joseph Brodsky said to me once upon a time, intensity isn’t everything. I believe Joseph was thinking then of Auden, the later Auden. The early Auden is intense, there’s a hectic staccato artesian kind of thing going on, there’s immense excitement between the words and in the rhythms. There’s the pressure of something forcing through. And then that disappears. In the 1950s and 1960s you have the feeling that things are being inspected from above. I suppose the transition comes when he writes those sonnet sequences at the end of the 1930s, marvelous, head-clearing sequences like “In Time of War” and “The Quest,” all vitality and perspective and intellectual shimmer. There is that sense of experience being invigilated and abstracted from a great height, but what is still there in that middle period is the under-energy of the language. Then finally that just disappears. And a kind of lexical burble begins to take over.

The Sylvia Plath section of Ted Hughes’ interview interested me.

I also loved Octavio Paz’ interview here, especially the excerpt below.

INTERVIEWER

Do you have to be in any specific place in order to write?

PAZ

A novelist needs his typewriter, but you can write poetry any time, anywhere. Sometimes I mentally compose a poem on a bus or walking down the street. The rhythm of walking helps me fix the verses. Then when I get home, I write it all down. For a long time when I was younger, I wrote at night. It’s quieter, more tranquil. But writing at night also magnifies the writer’s solitude. Nowadays I write during the late morning and into the afternoon. It’s a pleasure to finish a page when night falls.

INTERVIEWER

Your work never distracted you from your writing?

PAZ

No, but let me give you an example. Once I had a totally infernal job in the National Banking Commission (how I got it, I can’t guess), which consisted in counting packets of old banknotes already sealed and ready to be burned. I had to make sure each packet contained the requisite three thousand pesos. I almost always had one banknote too many or too few—they were always fives—so I decided to give up counting them and to use those long hours to compose a series of sonnets in my head. Rhyme helped me retain the verses in my memory, but not having paper and pencil made my task much more difficult. I’ve always admired Milton for dictating long passages from Paradise Lost to his daughters. Unrhymed passages at that!

INTERVIEWER

Is it the same when you write prose?

PAZ

Prose is another matter. You have to write it in a quiet, isolated place, even if that happens to be the bathroom. But above all to write it’s essential to have one or two dictionaries at hand. The telephone is the writer’s devil, the dictionary his guardian angel. I used to type, but now I write everything in longhand. If it’s prose, I write it out one, two, or three times, and then dictate it into a tape recorder. My secretary types it out, and I correct it. Poetry I write and rewrite constantly.

INTERVIEWER

What is the inspiration or starting point for a poem? Can you give an example of how the process works?

PAZ

Each poem is different. Often the first line is a gift, I don’t know if from the gods or from that mysterious faculty called inspiration. Let me use Sun Stone as an example: I wrote the first thirty verses as if someone were silently dictating them to me. I was surprised at the fluidity with which those hendecasyllabic lines appeared one after another. They came from far off and from nearby, from within my own chest. Suddenly the current stopped flowing. I read what I’d written—I didn’t have to change a thing. But it was only a beginning, and I had no idea where those lines were going. A few days later, I tried to get started again, not in a passive way but trying to orient and direct the flow of verses. I wrote another thirty or forty lines. I stopped. I went back to it a few days later, and little by little, I began to discover the theme of the poem and where it was all heading.

INTERVIEWER

A figure began to appear in the carpet?

PAZ

It was a kind of review of my life, a resurrection of my experiences, my concerns, my failures, my obsessions. I realized I was living the end of my youth and that the poem was simultaneously an end and a new beginning. When I reached a certain point, the verbal current stopped, and all I could do was repeat the first verses. That is the source of the poem’s circular form. There was nothing arbitrary about it. Sun Stone is the last poem in the book that gathers together the first period of my poetry: Freedom on Parole. Even though I didn’t know what I would write after that, I was sure that one period of my life and my poetry had ended, and another was beginning.

What will Athena Kashyap, the poet and teacher say? Come tomorrow evening at 6:30 to find out.

Leave A Comment