Tai Chi Me for Condenast Traveler US Edition

A piece I wrote about learning tai chi in Shanghai and Beijing. They took great photos of a tai chi master in New York.

Casting aside the yoga of her youth, Shoba Narayan turns to China’s martial arts to tame her wild emotions”I’m more Rahm Emanuel than Barack Obama”and get six-pack abs in the bargain.

I have come to China from my home in Bangalore, India, to find a tai chi teacher.

I arrive in Shanghai at night, alone, and decide to go to the movies. Neon lights flash by the taxi’s windows as the driver listens to mournful Chinese music. We pass buses full of commuters on their way home. The theater is almost empty, but the moviechelle Yeoh’s latest martial arts adventure, _Reign of Assassins_is breathtaking. Watching her dispense would-be killers with praying mantis strikes and wing chun kicks reminds me that Yeoh is heir to a long line of women in Chinese martial arts, something the feminist in me relishes. The earliest reference I’ve found comes from the Zhou period, around 700 b.c., when a young woman, Yuh Niuy, defeated three thousand men in a sword battle lasting seven days. Yuh’s sayings have been passed down the centuries. “When the way is battle,” she wrote, “be full-spirited within, but outwardly show calm and be relaxed. Appear to be as gentle as a fair lady, but react like a vicious tiger.” I sleep well in my hotel that night.

The next morning I jog to the Bund. At 6 a.m. it is quiet, a far cry from night, when throngs of people gather to gawk at the Oriental Pearl Tower and the lights of Pudong. Dawn brings runners like myself, plus dog walkers, photographers, kite-flying men. In the plaza across from The Peninsula hotel, several groups “play” tai chi, as the Chinese say, dressed in cream-colored satin uniforms, wielding swords and fans to strike poses such as “embrace the moon” and “cloud hands.” They are magnificent, crouching low to crawl like a snake and doing “golden cock stands on one leg.” A black-uniformed teacher breaks off occasionally to adjust a stance, demonstrate a parry, and correct a form.

During a water break, I sidle up to a young man whose explosive fa-jin punchesones that begin fast, then stop abruptlyalmost make me weep with envy. “Does your shifu [teacher] speak English?” I ask.

I don’t understand his words, but it’s clear that the answer is no.

My pursuit of tai chi has been punctuated by such cultural challenges. When I informed my conservative Indian family that I was interested in tai chi, they were appalled. Why was their Indian child, heir to an ancient and proud traditionyogaleaning toward an alien discipline? “I told you that sending her to America was a bad idea,” said my uncle, who made me do the downward dog every day as a child. He was right. It was as a young woman abroad in America that I’d found myself bumping up against China’s culture: a Chinese roommate, an apprenticeship with an acupuncturist while awaiting my green card, Bette Bao Lord’s novels. Yoga is like my mother; I take it for granted. It is so much a part of me that I am tired of it. I want some distance. Tai chi offers this distance while still being based on the Eastern principles familiar to me.

I am here, in tai chi’s birthplace, to try to take my practice to the next level. Like many modern practitioners of tai chi, I don’t have the free time to spend weeks at one of the intensive martial arts schools in the provinces of China because of work and family responsibilities. Instead, I have seven days. And so I’ve made appointments with tai chi teachers in Shanghai and Beijing. My tai chi teacher in India, who travels frequently to China, tried to manage my expectations. “My teachers cannot be yours,” he said. “Go forth and find your own.”

Having turned forty, I no longer aspire to become a crouching tiger or a hidden dragon. Yes, I want the core strength, flexibility, and balance that tai chi provides. But I also want serenity. Temperamentally I am more Rahm Emanuel than Barack Obama. I hear myself interacting with my family, issuing threats to my daughters that I have no hope of keeping (“Clean your room or no TV for a month”) and subjecting my even-keeled engineer husband to ultimatums (“This is not workingI am leaving”). With tai chi, I can channel my frustrations into black tiger kicks, dragon fists, and eagle claw holds.

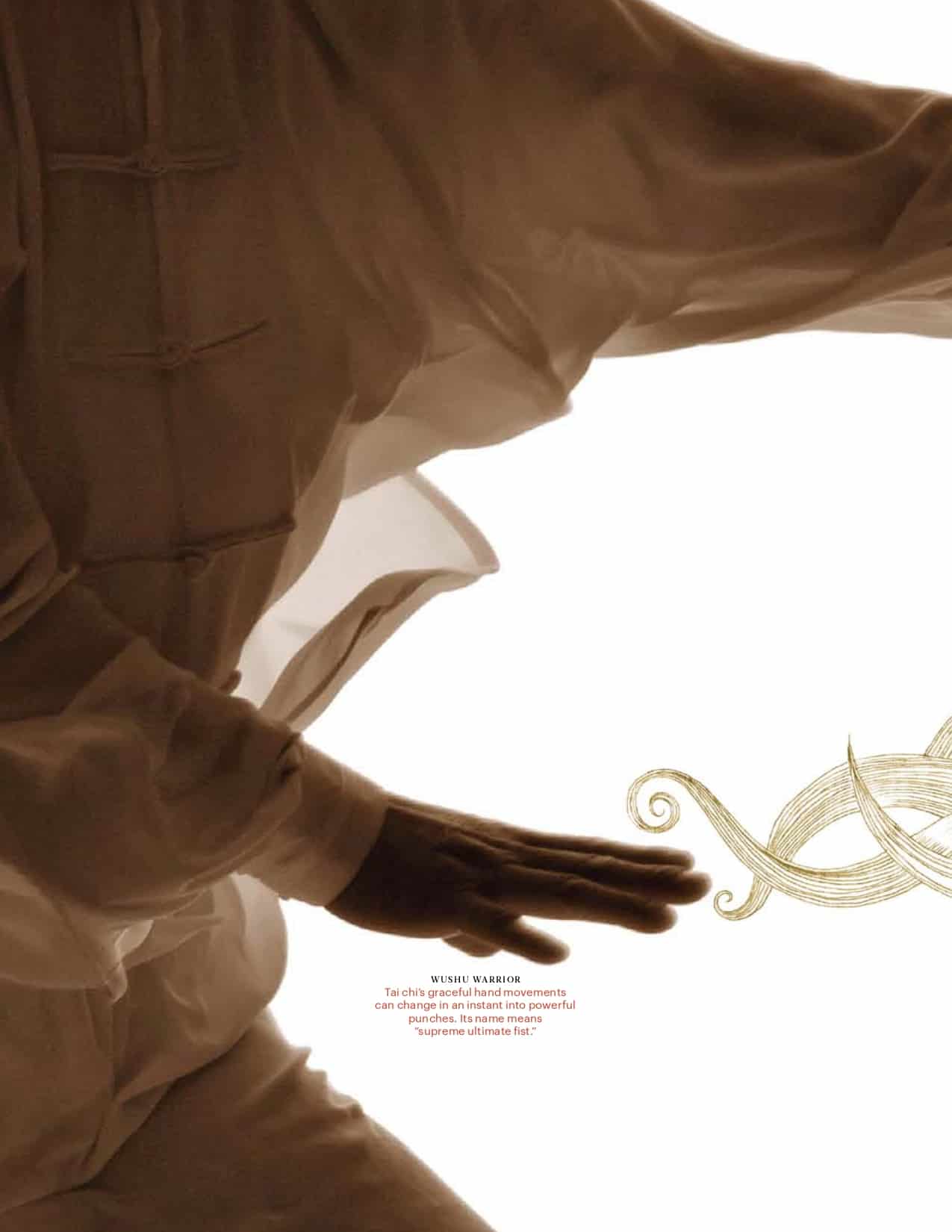

Tai chiwhich means “supreme ultimate fist”is arguably the most popular of the three-hundred-odd Chinese martial arts, known collectively as wushu. Like yoga, tai chi begins with external flexibility and balance before moving inward. The idea is to do the pose repeatedly until it changes your posture, improves your belly breathing, makes your joints flexible, and centers your mind. Legs ground the body and provide balance. Energy originates in the feet before flowing upward to waist, chest, and arms, gaining momentum along the way until it explodes outward through punches or kicks. Tai chi practitioners try to remain relaxed while moving so that this energy can flow without obstruction.

In the United States, about 2.3 million people practice tai chi, according to the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Studies show that regular practice can help reduce cholesterol, heart attacks, and high blood pressure as well as osteoarthritis, sleep disorders, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. One study reported a forty percent reduction in the number of falls in an elderly group practicing tai chi.

The Chinese government’s relationship with tai chi is conflicted; the authorities recognize its value as a tool for well-being in a nation enduring a health care crisis, but also fear its cult power. The practice of Falun Gongwhich uses the principles of tai chi and qigong, or controlled breathingwas banned by President Jiang Zemin in 1999. The move stemmed from a peaceful protest by ten thousand followers outside the Zhongnanhai government compound against a government-ordered media campaign opposing Falun Gong. Many Falun Gong practitioners remain in prison today.

Shaolin, meaning “Young Forest,” is a monastery in the Song Shan Mountains of Henan Province. Legend has it that an Indian monk, Bodhidharma, traveled there in the sixth century, stared at a wall in silence for nine years, and taught the monks martial arts techniques, which they used to defend the emperor. Shaolin-style wushu, which emphasizes discipline, penance, and brutal practice as a way to achieve superhuman strength and skill, is a “hard external” wushu method that lends itself to combat, in contrast to softer “internal” wushu styles that focus on health and longevity.

For centuries, Shaolin was the only way. Neijia, or internal, styles originated with a Taoist monk, Zhang Sanfeng, in China’s Wudang Mountains in the twelfth century. Zhang observed a snake fighting a crane. Every time the crane struck, the snake would dart its head out of the way and hit the crane with its tail. Even though the crane was bigger and stronger, the snake eventually won. From such observations, Zhang came up with the basis of many of China’s non-Shaolin martial arts: to yield in the face of aggression, to turn your opponent’s strength against him. Tai chi comes under this category.

While I am not a Shaolin student, I want to take a traditional Shaolin class, so I visit Longwu Kungfu Center, an urban day school in Shanghai. Longwu is a large open space with mirrors for walls, like a gymnasium. On one side, a master is teaching Shaolin-style wushu to a group of Chinese and foreigners. Tall and swarthy, he yells his commands in English that sounds like Chinese: “Forwa, fiit togetha, kicku, handsup, whaaa. . . .” A dozen students lift their sticks and strike. “Whaa!“

I stand in the back and follow the class to the best of my ability. Many of the movements overlap with tai chi, but the use of the stick, and the sudden punches, are new to me. Across the hall another master, bare torsoed and balding, is giving a private boxing lesson to a helmeted man who seems unable to dodge his lightning punches.

I ask Longwu’s founder, a former national wushu champion named Alvin Guo, how he manages to attract such high-quality instructors. “An old Chinese saying goes, ‘Once a teacher, always a father,'” is his enigmatic reply.

I spend the next two days in Shanghai taking tai chi lessons at Longwu and two other places, the Jingwu sports training center and the Qingpu school. None of the three tai chi teachers I meet are for me. One is more interested in how much I can pay per hour than in advancing my practice. The other two are better but don’t speak even rudimentary English. (I had e-mailed them before my arrival and their responses were in English, apparently sent through senior students.) They nod approvingly when I show them my techniques, adjust my arms and body, but we don’t progress beyond that. There is no conversation.

Recognizing the right guru is the stuff of lore in Eastern thought. I too have some parameters. There has to be that intangible connection, of course. Beyond that, I seek generosity. In ancient India and China, when it came to spiritual disciplines, knowledge was a gift that gurus offered for free to worthy students. It was understood that the student would then make an offering, to solidify the connection. All of my teachers in India and the United Statesthe good ones, anywaytaught me for free. I am hoping that this pattern will continue in Beijing, where I fly to next.

Beihai Park is the loveliest in Beijing. Weeping willows border the lake, and with several tai chi groups practicing a variety of forms, you can cherry-pick one that is right for you. I join a gathering of women who move to the sound of tinny Chinese music from a small tape player. One of them, a radiant young mother, offers me her sword as she takes a break to comfort her baby in a nearby pram. I shake my head and try to explain that I am not at her level. She smiles, insisting. I am secretly thrilled. Sword tai chi is more nuanced and subtle because of the strength and speed of a sharp instrument. Movements such as “swallow skims the water” and “black dragon wags its tail” take on more gravitas as I execute them.

Later that day, looking up tai chi classes on the China Culture Center’s Web site, I am distracted by a lecture on “cricket fighting and chirping culture” and decide to attend. I make my way to the center, located in a large, squat building in a quiet neighborhood, where founder Feng Cheng lectures in English, speaking poignantly about how the Chinese love to catch and keep crickets.

He tells of cabbies who drive the night shift with a cricket in a box inside their shirt so that they can listen to the comforting sound of their pet during the long, lonely night. Why, I ask Feng, are the Chinese more fond of crickets than of the dragonflies or butterflies I caught as a child in India?

“Because they fight,” he replies simply.

I come back the following evening for a 7:30 tai chi class. The teacher, thirty-eight-year-old Paul Wang, has the light, playful quality you see in Buddhist masters. With his bald head, ascetic appearance, and thin body, he looks like a monk, which he is not. “The baldness is just my hairstyle,” he says with a laugh.

I have high hopes. Perhaps he is the one. After class, we get to talking.

“Sometimes when we meet a difficulty, we have a lot of tension and hurry to fix the problem,” he says. “When you master the way of balance and gentle intention, everything you face will be different. There will be less hurry, your mind will be very clear. When someone is aggressive, you normally become tense. But that is the moment when you must practice your tai chi to release the stress. First, don’t have resistance to yourself; then you won’t have resistance to the other person. If he is aggressive, simply accept his moves and reflect the aggression back at him.”

Wang is a highly accomplished practitioner, but I cannot get past the smoothness that he has cultivated to deal with the expats and foreigners. I crave the artless roughness of the old masters.

I’m looking forward to taking a tai chi class at the Beijing Sport University when I learn that it’s canceled. At the Fairmont Beijing, where I am staying, the tai chi instructor, Link Li, offers to give me a free lesson. I am disdainful. Learning tai chi at a luxury hotel? How good can the instructor be?

But over the course of two lessons, Link improves my technique manifold. He tells me to take “soft heavy steps with flexible strength.” This means that while I must tread softly, I must be firm, be “heavy” with intent. At the same time, I must have flexible strength so that I can move quickly when attacked. I watch as Link does the slower, dancelike moves that most people associate with tai chi, and marvel as he speeds up the same moves to demonstrate how tai chi used to be done in its earlier, more militant incarnation. It’s a revelation to see poses known for their health benefits transformed instantly into weapons.

When he was just twenty-five, Link tells me, he was authorized by his teacher, a prominent master known as Gao Yong, to take on students. Who knew that this smiling thirty-year-old hotel employee was a bona fide shifu?

At the end of the session, I chat about tai chi with Link. Like Wang, he is highly skilled and eager to cater to my needs. And that’s what’s bothering me, I realize. I don’t want to be treated like a tourist on a tight schedule but rather like a student away from the constraints of time and family. I want a teacher who will be true to himself or herself, not fuss over me. I am looking for someone raw, someone who can bring the mountain air of Wudang into my consciousness.

It is my last day in Beijing, and I am desperate. Fool, I berate myself, questioning my hope of finding a teacher, people train in China for monthshow could you expect to accomplish anything in a week?After my morning round of tai chi at Beihai Park, I return to the hotel to find an e-mail from one of my tour guides directing me to a female shifu, Mrs. Shi, who leads tai chi at 10 a.m. every day, rain or shine, by the old city wall on the south part of town.

The concierge gives me detailed directions. The subway ride takes an hour. I get out and promptly lose my way. I call Mrs. Shi on her mobile phone. She is friendly and giggles a lot but speaks mostly Chinese and is unable to guide me to her location. I find an English-speaking girl who shows me the way. I walk across a park cut through by a canal bordered by weeping willows. A manicured lawn on one side is full of seniors ballroom dancing, people playing badminton, mothers pushing babies in prams, young men jogging, and locals sitting on park benches and reading newspapers. Amid the ballroom dancers, I find Mrs. Shi’s tai chi class. Her straight hair pulled back in a ponytail, she has a face appropriate to her fifty-odd years but the body tone of a woman half her age. Her class is just ending. A middle-aged man gives her the fist-to-palm salute that we martial arts students offer our teachers. Mrs. Shi turns to me with a smile. I demonstrate my chen style (the oldest of five tai chi styles) so she can gauge my level. She watches me, and my hair starts to stand on end. It sounds crazy, but I feel a strange electricitythe kind of buzz you get when you are single and meet someone really attractive who could be the one.

I try to remove my jacket so that she can see the way my body moves more clearly. “I can see your form,” she says simply.

Then it is her turn. Her stomach coils (there is no other word for it), her knees turn, her back arches. She does things with her body that I have never seen before. When I marvel at her moves, she says, “Quantity equals quality,” and laughs in the fashion of Chinese people who are aware of, and embarrassed by, their poor English. “Tai chi is a life journey.”

I try to imitate her moves. I am awed by her energy. I am ready to prostrate myself and beg her to accept me as her student. But in order for me to know that she is the right shifu, there is one final test. I offer to pay for a private lesson.

“When do you want to start?” she asks.

Now, I reply.

Her face clouds. Tai chi is very “comprehensive,” she says. “Hard to learn in one day, one lesson. I can teach you one form,” she says. “No charge.”

Temple bells ring and sparrows sing. I have found my teacher.

For the next hour, Mrs. Shi takes me through the same stomach-coiling move that will, I know, if done regularly, give me six-pack abs. Her instructions are simple and often repetitive.

“Keep the back relaxed and the front tight. Yang in the back is expansive; yin in front is closed.” She touches my back. “Lower back loose, upper back tight. Quantity equals quality.”

She can see errors in my posture even when I think I am obeying her instructions. She tells me all this with a shining light of compassion and understanding in her eyes. “You are too much in a hurry,” she says. She might be referring to my life. “Wisdom requires patience.”

An hour later, Mrs. Shi says, “Do this movement sixty times a day for sixty days, and then you will begin to feel something. Once you feel something, come back to me and I will teach you the next lesson.”

We chitchat. She has one daughter, she says, who is twenty-one and living in India. What does your daughter do? I ask.

She is a yoga teacher, Mrs. Shi says.

I laugh. I cannot help but appreciate the irony of coming all the way from India to learn tai chi from a Chinese woman whose daughter is in India studying yoga.

I bow to Mrs. Shi, give her the martial arts fist-to-palm salute, and once more offer to pay for the class. Again she refuses. As I walk through the ballroom dancers, I turn back and find her watching me, waving.

I have to offer my shifu something. I am not even sure if I will ever see her again, although of course that isn’t the point. I have encountered a master who has changed my practice and potentially my life. She will reside in my mind, and I will pay homage to her before I begin my daily practice. But what to give her as an offering?

The midday sun is high in the sky, the grass invitingly green. The ballroom dancers turn. Melodious Chinese music wafts from somewhere. On the spur of the moment, I stop. The grass is my yoga mat. I wave at my shifu, who is still watching me. My elbows support my head as I bend and execute a perfect headstand. Years of practice as a child still haven’t left me. I am doing the Sirsasana yoga pose in a Chinese park as an offering for my tai chi teacher. Someone claps. I get back up on my feet, wave at my shifu, turn, and head to the subway for the long ride home.

Places and Prices: Learning from the Masters

by Shoba Narayan

If you’ve got plenty of timesay, six monthsa very understanding family, and a well-connected shifu(teacher), you can ask him or her to put you in touch with _shifu_s at the Shaolin temples in Henan and Fujian province. Once you show up, however, you’ll still have to do penance until a master accepts you. A less strenuous option is to take a martial arts immersion trip with a tour company such as SCIC Beijing (347-410-5055 in New York; 14 days, about $1,600 per person) or China Taiji Tour (86-29-133-1918-1406; 12 days, $2,650 per person).

If you prefer a serious academic tai chi environment, you can apply to programs at China’s sports universities and learn Chinese in the bargain. Allied Gateway offers month- and semester-long martial arts study at universities in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou (86-20-8563-0680; in Beijing, a full semester is $6,835 in a single dorm room, $8,216 in a hotel; a four-week intensive course is $2,440 in a single dorm room, $3,891 in a hotel).

If tai chi isn’t your focus but you’d still like to get a taste, there are drop-in classes at urban day schools such as Beijing’s Milun School of Traditional Kungfu (86-138-1170-6568; group class, $15; private lesson, $38) and Shanghai’s Longwu Kungfu Center (86-21-6287-1528; group class, $15; private lesson, $30). My teacher in Bejing, Mrs. Shi, gives private lessons. Look for her at the Ziweiruhua pavilion in Yuandadu Relics Park between 6 and 9 a.m. or call in advance for an appointment (86-138-1189-5462; two hours, $60).

With classes on everything from cricket fighting to tai chi to Chinese landscape painting, Beijing’s China Culture Center is a terrific place to get your cultural bearings (86-10-6432-9341; chinaculturecenter.org). The tai chi master demonstrating the moves in this article, Dr. Nan Lu, is the founder of the Traditional Chinese Medicine World Foundation, in New York, which offers tai chi classes and a variety of courses in Chinese medicine (212-274-1079).

I, too, am searching for a Tai Chi teacher like your Mrs. Shi! I was living in Wuxi (just a short 34 min. high speed train ride away from Shanghai) and, before leaving Germany, my Swiss dr. recommended I take up Qi Gong or Tai Chi. Trying to find anyone in China who outright teaches Qi Gong proved quite difficult. However, shortly after moving into an expat neighborhood in Wuxi, that’s becoming less expat-like and more wealthy Chinese-like, I asked a “black car” driver (unlicensed taxi driver) from Anhui whose English was pretty good, if he knew of a Tai Chi master anywhere in Wuxi. He told me there was a master living right in our compound. I got Master Guo’s telephone number from him and gave it to a Taiwanese woman who was a member of the Wuxi International Club that I’d recently joined who had just sent out an email message announcing the start of Tai Chi lessons as soon as she found an instructor. Master Guo is an exceptional Tai Chi master, one who has risen to fame and is originally from Beijing. He taught our small group of expat women for the first few weeks, commenting that, if I would learn Chinese, he would make me a master, but once he saw most of those in the group were not as committed as he’d like us to be, he stopped coming and sent Wang shi fu (a woman in her 60s) in his place.

I’ve sinced moved to Shanghai and have been searching for a Tai Chi master since arriving in late Dec. I actually spoke with Alvin Guo last week (no relation to my Wuxi master) and have not yet been to his place to check things out. It’s frustrating…I feel I could better learn back in the US than here in China, which is ironic…..something you, too, experienced. Although I live just minutes away from Zhongshan park, where Chinese “play” Tai Chi every morning, I’ve yet to meet anyone who is as good as Wuxi Master Guo, who also speaks a bit of English.

My husband’s Chinese assistant was in touch with Master Guo last week, because I met a local man in Zhongshan park who had heard of him and thought that 2 of Guo’s students were teaching in Shanghai. After speaking with him he told her his students were no longer teaching but that he might have other recommendations. Since he was traveling when she contacted him he said he would contact her upon his return. I hope to find someone soon as we are only here for one more year and, as Master Guo said, it takes at least 5 years of constant practice to become a master.

I wish you luck in reaching your goal of becoming a master yourself!

Best regards,

Toni

Does it feel possibly somewhat arrogent to expect to find a master that will teach you only in your language, rather than you making the effort to learn theirs .. even just out of respect? Or to find a master that will consider you a “worthy student” in one easy lesson….There are incredible instructors in Zhongshan park..but none that will make you a “master” on your schedule…if you can learn to breath, relax your mind a bit and achieve some small measure of connection between the two in a year you will have accomplished something magnificent.

Further irony – there’s an English speaking tai chi master in Chennai, if you are interested.

when the student is ready, the “master appears”…. you might discover that the way is in practice no one infuses you with magical chi like meeting at a singles bar to evolve your form.. go to a park and practice to the best of your ability, put in some honest, consistent effort.. at some point , someone of a higher level than you will offer advice to improve, incorportate it and grow… i have never met a master that would allow anyone to call them a master..

Could you recommend where can i learn tai chi in Bangalore? Thanks!

Avinash Subramanyam

http://www.seefar.in/

Hi,

I am really sorry to perform necromancy on your blog. But I can’t find any contact details on seefar.in and they aren’t responding to emails! Can I trouble you for alternative contact details or alternative place to learn Tai Chi in Bangalore?

Thanks so much!

BTW awesome blog post! I stumbled here when searching for Tai Chi classes but got addicted to the blog posts here as a result!

Hi KrishnaRules :)

My friend and teacher, Sensei Avinash Subramanyam, has received your email and replied, they said. Anyway, you can try [email protected]

Otherwise, you can contact his assistant, Priya. With her permission, I am giving her mobile number here. 91 9620239910

Good luck!

He is an amazing teacher.

Thank you so much!

It can be useful. I wodlun’t have stuck with it for 8 years if it was completely useless. I just found that its proponents (like proponents of anything) over promised and under delivered.Alternative health care providers also don’t seem to know when they are in their circle of competence and when they are not. This is not just limited to them, but I found this to be a big thing where a provider could help me with one thing and then claim to be able to help me in other areas where they were clueless.